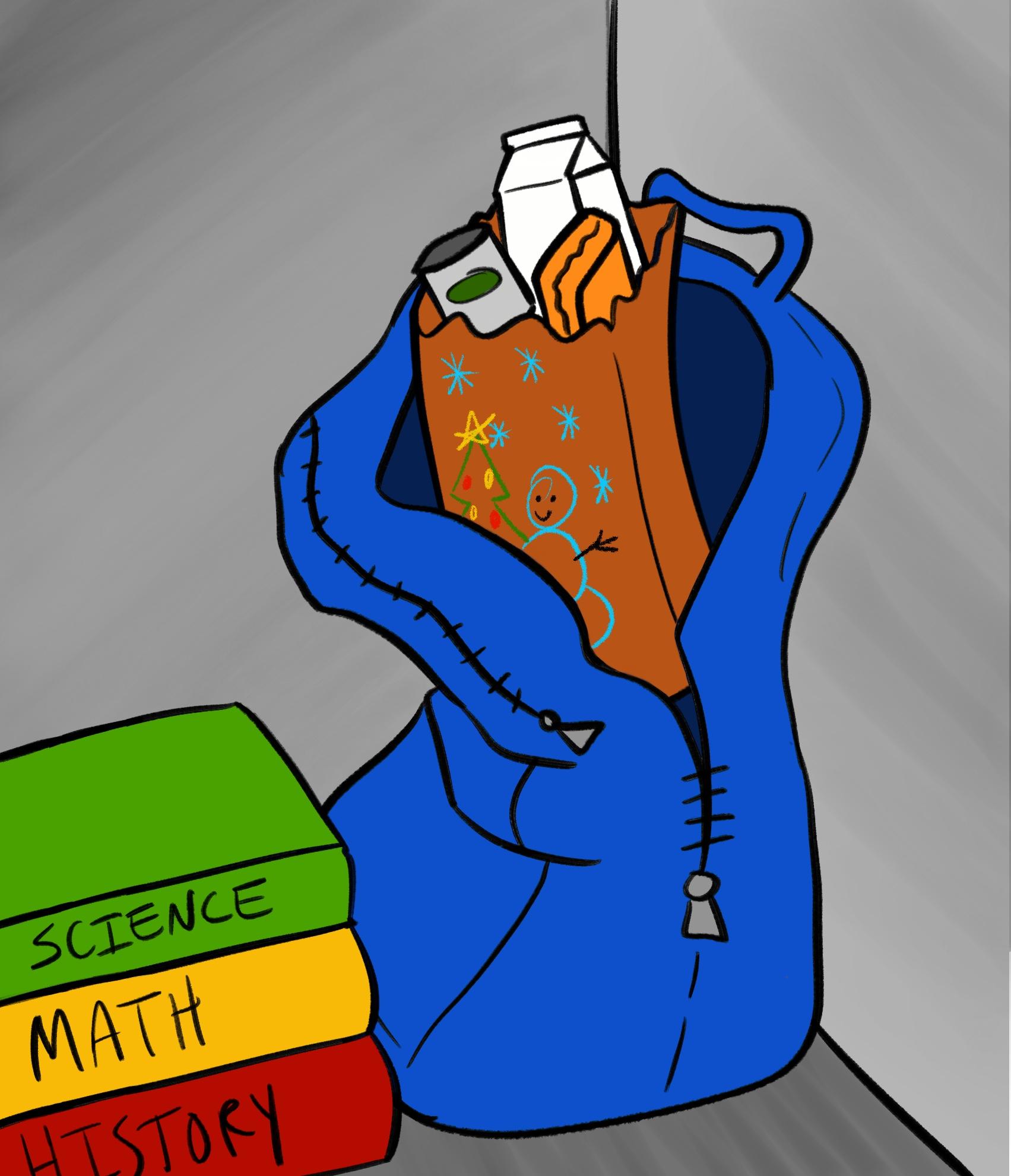

When the days get shorter and colder and communities near their holiday celebrations, small hands stained with Crayola markers work feverishly in school to decorate brown paper bags for children they don’t know. Shoving handwritten notes inside the bags, the children may not grasp the impact of the festive lunch sacks, an impact that reaches the lockers of hungry students across Warren County schools.

After decoration, the brown paper bags are filled with green beans, granola bars, shelf-stable milk and other easy-to-prepare foods in a small office at 1133 Adams St. all because a coalition of people want to help the kids who go home to empty pantries. Jodi Traen leads this initiative, called the Bowling Green Backpack Food Program, all while balancing other unpredictable jobs and the boxes of food stacked to the office ceiling.

“I lose sleep at night worrying about the kids who aren’t getting that meal,” Traen said. “Especially when there are so many resources around here to provide food and shelter for these families.”

According to Feeding America, Kentucky’s Heartland, one in five children in Kentucky struggle with hunger. While Christmas break is a big gap in a students’ access to food distributed at school, the food program feeds as many children as it can every weekend and break of the school year. Out of the near 1,000 applicants in Warren County, the food program only has the resources to serve 410 across 25 public and private schools. Traen said there are still many more than those who apply.

“We live in the largest county, land-wise, of all the counties Feeding America serves,” Traen said. “Of all the organizations and companies we have, there is no reason why a child should go home hungry. There just isn’t — we’re not a third-world country.”

Traen is originally from St. Louis, but she lives in Bowling Green with her husband and son, who has autism. She has two dogs, but as part of her doggy day-care service, she currently shelters five. On top of her full-time job as a caretaker, she spends more than 50 hours a week at the food program and has no problem spreading the ugly reality of an unknown corner of Bowling Green.

“I’m always trying to put the needs of the kids who can’t help themselves above mine,” she said.

Traen has lived and served all over the United States. From helping the homeless and those who are homebound to soup kitchens and Meals on Wheels, she found her way to Bowling Green’s St. Vincent de Paul as interim president. Quickly after taking that position, those previously running the food program, Hope House Ministries, were looking for confident hands to pass the project onto. Traen took the position in stride and has been in charge for the past four years.

Traen believes the community’s responsibility is to help the children be successful. Based on the lack of resources the program has, though, it is clear to her that not many people are aware of the hungry children in their backyard.

“These kids go home on the weekends to houses with empty pantries and cupboards, and many of them have working parents who cannot always be home to support them or who have too many mouths to feed,” Traen said. Many refugee children have parents who haven’t found work yet.

Through Feeding America, Kentucky’s Heartland, it costs $3 to feed a child for the weekend and $120 to feed them for the entire school year. Because this organization can buy in bigger bulk than a regular consumer, things like applesauce cost around 10 cents a cup.

Traen oversees the food program and all of its volunteers. From dropping off boxes of food to school counselors’ homes for efficient delivery to fundraising and spreading awareness, she is constantly disappointed by how little the food program can help.

“It seems to be getting worse, not better,” Traen said.

Surrounding counties come to Bowling Green to shop, for medical procedures and other services, and Traen said there’s a notion that this area has enough. If a high school is known as the school with rich kids, people neglect the kids that still go home to no food. There are always people who don’t think the support is necessary.

Because of the lack of resources, Traen has to be selective with which children are benefitting from the food program. She has made it her mission to add more students to their list by the time Christmas comes around, but to her, it’s never enough.

“Just because a child is on free and reduced lunch or identifies as low-income doesn’t mean they automatically qualify for the program,” she said. “For now, we can only give out food to those who are in the worst of the worst situations.”

Those without food suffer from disadvantages across every aspect of their lives, including health problems. For children in school, it hinders their attention span, emotional control and overall ability to succeed. Traen believes schools have to do everything in their power to educate their children and help them be successful. Communicating that to those unwilling to listen, she hopes her long nights at the office continue to pay off.

“School is hard enough with the bullying and the violence,” Traen said. “Food should not be an issue.”

It’s hard for Traen to raise a son with autism in a world that stigmatizes his special needs. She helps him face his challenges daily and sees firsthand the disadvantages so many have because the world wasn’t built for them to thrive.

“As a parent of a child with special needs, I see the raw deal he has been dealt,” she said. “It’s frustrating. They’re not welcomed in places, and their life just kind of stinks. I want to make it easier for him and the kids who feel the same way about their lack of food access.”

In order to benefit from the food program, parents, teachers or children themselves will reach out to the youth and family counselors at their school. While 1,000 applicants seems like a big number, Traen said it’s not even close to the unfathomable amount of hungry kids in Warren County. The food program is only serving around 50% of the children who have applied.

The holidays are when families walk into supermarkets and see the big bins filled with gifts for children who have less and are when people feel compelled to be more generous than usual. So, when those brown paper bags get sent to homes around the county, they include “luxuries” like a new toothbrush and tube of toothpaste.

On a regular weekend, the plastic bags are filled with Kraft mac and cheese, mandarin oranges, peanut butter crackers, ramen noodles and some kind of breakfast cereal to pair with the shelf-stable milk that doesn’t have to be refrigerated right away.

The hungry children at South Warren middle and high schools experience the work of magic every Friday afternoon when they open their locker doors, and tucked neatly into their backpacks are the bags filled with nourishment for the weekend. Gina Powell, the youth services coordinator at these schools, is the magician.

Every Friday while the students are in class, Powell works her way around the school, placing food into the students’ backpacks to relieve them of the burden of being singled out among their peers. Powell wants to respect the privacy of the students who are hiding in the middle-class lifestyles that they don’t really fit into.

“No one wants to walk onto the bus carrying a Walmart bag filled with ravioli and Capri Suns,” Powell said. “Maybe it’s a single mama, or a family who has run out of food stamps halfway through the month. Either way, we don’t want to embarrass the kids in a place where they’re just trying to fit in.”

Children can be mean, and food program volunteers don’t want a child to be singled out for being hungry when there are so many resources that could be available to help them.

In the small Adams Street office, volunteers range in age from 20-year-olds to elderly, and they assemble the food packages every week. Jennifer Vaughn, the volunteer coordinator, is Traen’s right-hand-woman.

Vaughn works closely with Traen to ensure the weekly process runs smoothly. Coordinating drivers and packing boxes as tall as the nearly 10-foot wall in 1133 Adams St. are just the first steps to bringing food to childrens’ homes.

Vaughn watches Traen’s face light up every week when the bags are delivered, especially during the holiday season when it isn’t just the children who are receiving food — it’s the entire family.

Christmas time is a time of community and service, but it’s also a time when those who struggle struggle the most. The number of children needing help from the food program has quadrupled just in the years that Traen has been in charge.

The most important part about the program is that it continues to grow in its reach, because without the volunteers and donations from the community, the children wouldn’t eat.

“If I’m ever feeling down or depressed, I can just go help serve others, and it takes me out of my own head,” Traen said.

The holiday season is coming up soon. School children are decorating brown paper bags, and the food program is hoping to add 150 more kids to their list of 410 by Christmas. Two weeks without a constant food source is two weeks too long, Traen said, and they need help.

“If I could teach my kids anything, it’s to help those who can’t help themselves,” she said.