On Saturday, March 24, crowds gathered in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to participate in March for Our Lives events to advocate for an end to gun violence in America. Join several of our writers and photographers as they document marches in three local cities: Nashville, Bowling Green and Calvert City in Marshall County.

Click on each tab to read the story and view photos from each event.

Advertisement

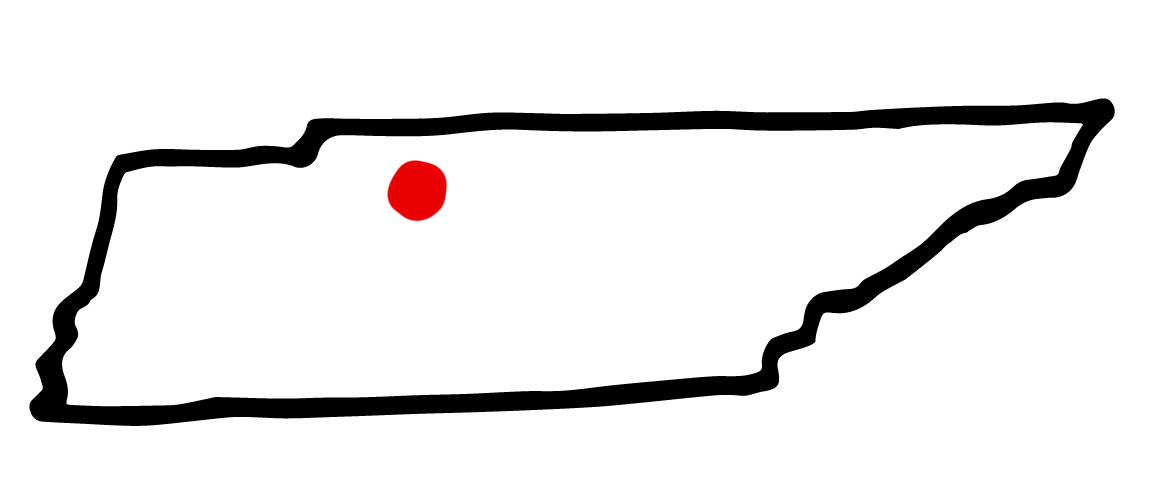

NASHVILLE

by Adam Murphy | photos by August Gravette

Thousands of students, parents, teachers and activists walked together in Nashville for the March for Our Lives, packing the street with people from sidewalk to sidewalk.

The air in downtown Nashville reverberated with chants and music throughout the march. The March for Our Lives was started to advocate for gun control legislation in response to the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, in February. In solidarity with the national march in Washington, D.C., over 800 “sibling marches” were held across the globe.

Vanderbilt University freshman Abby Brafman, a Stoneman Douglas graduate and Parkland native, said the people from her hometown inspired her to organize a march in Nashville. She said that after she had flown back from Parkland, she made the event on Facebook and expected approximately 50 people to attend. Over the next four days, over 7,000 people had said they were going or were interested, she said.

Abby Brafman’s family was incredibly supportive of her organizing the event, she said. Suzanne Brafman came to Nashville three times in the month before the march to help. She said people asked her if she was proud of her daughter for being an advocate.

“I’m proud of my kids all the time,” Suzanne Brafman said. “This is different. This is like stratospherically proud.”

Abby Brafman said that almost 100 of her Vanderbilt peers reached out to her to volunteer and work to set up the event. She said the people of Nashville were compassionate and supportive, despite the fact that she’d only been in the city for a short time.

Abby Brafman said she was in class at Vanderbilt when she received a call from her high-school best friend telling her that there was a shooting happening at their high school. She said she contacted her friend, who is still in high school, who replied with a message that read, “I’m fine, don’t worry.” Brafman then contacted her mom, who lives five minutes away from the school, and a wave of information started coming in — both news and rumors.

“We’re finding out one person was hurt, two people were hurt, someone was shot in the leg — one person is dead, two people are dead, five people, and so on,” Abby Brafman said.

Her mother, Suzanne Brafman, told her the final news that 17 people were killed. Abby Brafman remembers hearing rumored names of the shooting victims, including teachers she had grown up with.

“All of the dead were one person removed from me, “ Abby Brafman said, “Four of them were from my synagogue. It’s just a direct impact on my community.”

And so, just over a month later, Abby Brafman kicked off the march with a speech, followed by Nashville mayor David Briley. Abby Brafman spoke about the change in identity that gun violence survivors go through — that they would never lose the title of survivor.

“I’m not a lawyer. I’m not a politician. I’m a student,” Abby Brafman said.

Franklin, Tennessee resident Lee Hostettler said she said she came to the march to advocate for her granddaughter. She said society was waiting for students like Abby Brafman to come and fix things.

“My granddaughter shouldn’t have to be fearful of getting shot when she walks out the door to go to school,” Hostettler said.

A junior at Madison Academic Magnet High School in Jackson, Tennessee, Cameron Lewis organized a group of five friends to come to the march. Lewis also organized his school’s walk out on March 14. He said he organized these groups due to the sympathy that he felt for the survivors of school shootings.

“You get the feeling that that could happen to me and I would never know the better,” Lewis said.

The march involved people of all ages, races and professions walking together through downtown Nashville. People both young and old led chants and carried signs with phrases like “dump the NRA” and “arms are for hugging.”Parents brought their kids, lifting them onto their shoulders as they walked.

The march ended with a rally at the Public Square. There were multiple speakers, including 7-year-old Nora Hooper, who won the national writing contest held by March for Our Lives. There were also initiatives to register people to vote. Abby Brafman said this indicated that people were taking action beyond marching.

“I am proud to be an American,” Abby Brafman said, “This is the America that I have seen in textbooks, in movies throughout my entire life. I march, and I cry, and I gather people so I can feel American. I am goddamn proud to be an American teenager.”

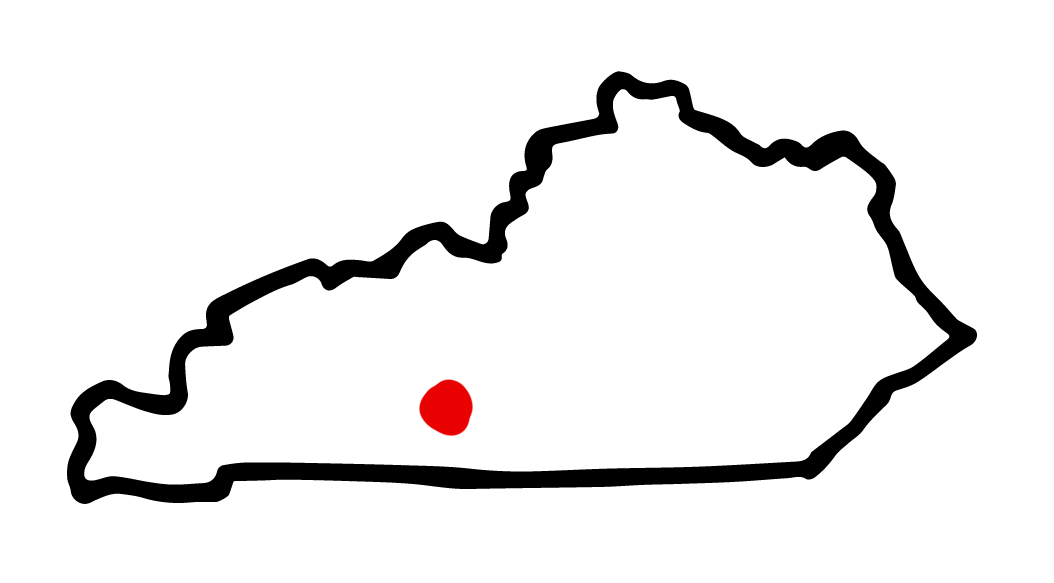

BOWLING GREEN

by Griffin Fletcher and Grace Pritchett | photos by Grace Pritchett

In Bowling Green, the rain poured relentlessly as students and residents huddled under the portico at Cherry Hall while others stood below, their umbrellas popped open in a colorful display. A mother held her daughter with her arms wrapped tightly around her shoulders. The march of nearly 200 people proceeded down College Street as people held up signs bearing phrases such as, “never again,” “students Demand Action,” and “am I next?” People shouted phrases like “Books not bullets” and “What do we want? Gun control! When do we want it? Now!”

Campbellsville senior Jeremy McFarland, who served on the planning committee for the march, said gun violence is just as much a local issue as it is a national issue.

“I think it’s always important whenever we have local marches,” McFarland said. “Gun violence is an issue in our community. It’s not just happening in the bigger cities.”

Upon learning that marches against gun violence were being orchestrated across the U.S., Leah Ashwill, director of the Center for Citizenship & Social Justice at WKU, began planning the sibling march in Bowling Green.

Residents who represented various organizations in Bowling Green, including Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America and Black Lives Matter, were also involved in planning and spoke at the march, McFarland said.

An activist for LGBT rights at WKU and in Bowling Green, McFarland spoke at the march about the effect of gun violence in Bowling Green’s queer community.

“The main thing that I wanted to talk about when I was up there is that gun violence is a queer issue, but it’s not the only queer issue,” McFarland said. “Gun violence is, and murder is, just one of the most extreme examples of greater cultural desire to remove queer people from existence and from society.”

Others spoke about the presence of gun violence within the black community and the community of Bowling Green as a whole. McFarland said that he believes the diversity in speakers at the march revealed the extent to which gun violence affects everyone, regardless of race, gender or sexuality.

“I think it’s important that we show how not only these issues are happening here, but who they’re happening to,” McFarland said. “And that’s why it’s important to bring in these different voices from different groups.”

Despite heavy rainfall throughout the march, many WKU students and Bowling Green residents took part and packed the center of Fountain Square Park.

“We were there to march for our lives, not march for fun,” McFarland said. “We’re to the point that we have to stand out in the rain for three hours.”

Lisa Goldy is a member of Bowling Green’s Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America group, which is part of a national organization that advocates for common sense gun reforms. It was started in 2012 in response to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting that took place that same year, according to the organization’s website. Goldy said she joined the group to advocate for the safety of the Bowling Green community.

“I’m here on behalf of the health and wellness of our children and community members,” Goldy said. Goldy later said, “I’m active in this community, and this was just a venue that I felt had the right message. It’s just common sense.”

Goldy said she is not against the Second Amendment but believes in stricter regulation. Goldy said that she believes suicide among teenagers in the U.S. is a statistic that could be lessened if stricter gun regulations existed, given that nearly 2,500 teenagers died by suicide, largely by firearms, in 2016, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

“Death by suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem or feeling,” Goldy said. “It all comes down to access to guns.”

Anyone aged 18 years or older may purchase a shotgun or rifle from a licensed dealer in the U.S., and anyone of any age may purchase a shotgun or rifle from an unlicensed person in the U.S., according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence website.

Haley Rinehart leads Bowling Green’s Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America group, which was founded about a month ago. Rinehart said that she decided to lead the movement because she believes common-sense gun laws should exist, even in a small town like Bowling Green.

“When they see a little town like Bowling Green marching in the freezing rain, that speaks volumes,” Rinehart said. “I just want people to realize that gun violence can happen anywhere.”

Rinehart, the mother of a child affected by firearm misuse, spoke at the march from a personal perspective. Rinehart’s son, Eli Parker, lost his eye while accidentally firing a misplaced gun at 4 years old. Rinehart said she hopes the march and similar marches will motivate Bowling Green citizens and fellow Kentuckians to vote in legislators willing to fight for common sense gun reform, locally and nationally speaking.

“The community needs to see that there are people that have been or could be targeted victims of gun violence,” Rinehart said. Rinehart later said, “If we can get them to speak up here, maybe we can get them to show up at the polls.”

Parker, who is now 20, said he believes the “emotional, physical and mental trauma” he experienced through gun misuse is something no one should have to deal with. He said he believes gun reform is a topic that needs to be discussed, starting with legislators.

“Something needs to change,” Parker said. “We can’t change anything until we get the people in there that can change something for us.”

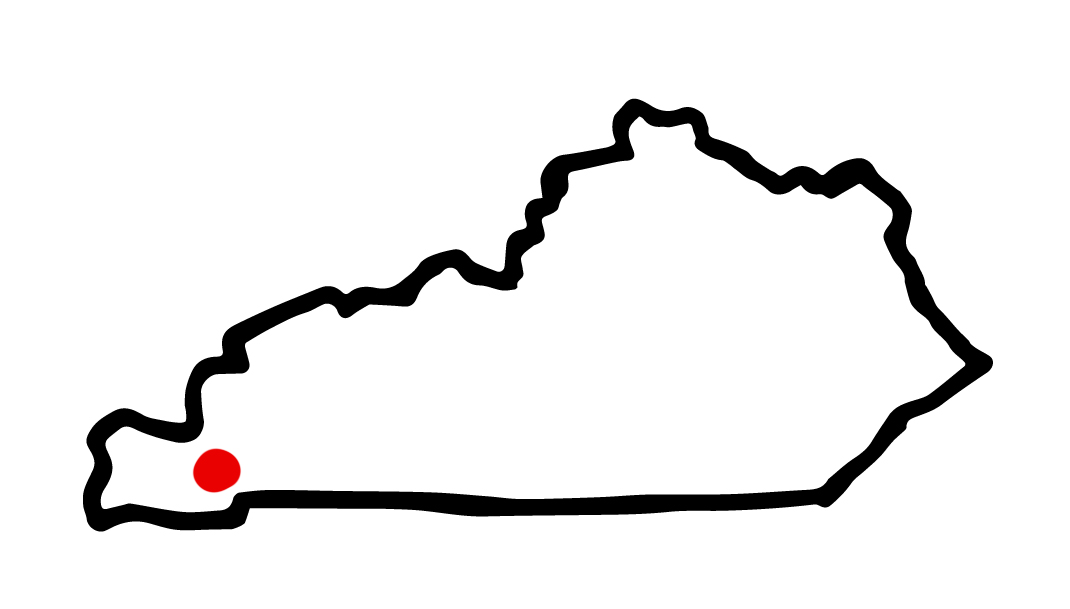

CALVERT CITY

by Helen Gibson | photos by Lily Thompson

They marched, chanted and held homemade signs. They advocated for tighter gun laws and regulations. They were inspired by the student survivors of the Feb. 14 shooting in Parkland, Florida, that claimed 17 lives a little more than a month earlier.

This weekend, a group of around 300 people in Marshall County, Kentucky joined people in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. participating in March for Our Lives demonstrations. Some of them knew all too well the effects of a school shooting.

After all, it had been only two months and one day since their community had been rattled by such an event.

On the morning of Jan. 23, before classes even began, a shooter started firing rounds in the commons area of Marshall County High School — the very spot where generations of Marshall County students had gathered to attend school dances and to hang out with friends in between classes. The gunfire killed two students, and 18 were injured in the midst of the chaos.

In the days and weeks after the shooting, Heather Adams said she watched her son, MCHS freshman Seth Adams, struggle to process the event that had taken place.

“We were struggling bad with anxiety and really awful panic attacks and stuff,” Heather Adams said. “And then that shooting happened at [Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School], and that was enough. You know, we had to do something.”

She, her son and several other students and community members started planning a Marshall County March for Our Lives event, to be held in conjunction with similar marches across the country. Heather Adams said the students did “99 percent” of the organizing and that it proved to be beneficial in helping them take action and express their grief.

“It’s been a very cathartic experience for [Seth] to be able to do this and feel the support of his community,” Heather Adams said.

Minutes before the event was scheduled to begin, rain drizzled down from the sky. A crowd of community members clutched umbrellas and handmade signs, unfazed. They were small children in strollers, older individuals with snow-white hair, and people in between. They gathered around a small, covered stage where a podium was set up.

Students and well-known community members sat in a semi-circle on this stage, and one-by-one, they left their seats, stood behind a microphone and addressed the crowd. Overhead, the long ladder of a fire truck suspended a giant American flag in the air.

Many of the students who spoke attended Marshall County High School and had been there on the morning of Jan. 23. They spoke with anger, outrage, fear, emotion and sadness in their voices, but they made one thing clear: Inspired by the students from Parkland, they wanted to make a change.

“School shootings were basically taboo to talk about before the students of Parkland decided to stand up,” Hailey Case said. “We look to our government, to the adults of this nation, to keep us safe. We trust them to save our lives because that’s what they promised to do. We trust them to always put us above everything else because that’s what they said they’d do. But they didn’t.”

Case, a freshman at MCHS, had been particularly nervous to address the crowd. But as soon as she finished, her friend Lela Free wrapped her in a hug. Case found her seat on the stage. A small smile stretched across her face; she almost looked as if she could cry from nerves and sheer adrenaline.

Soon, it was MCHS junior Keaton Conner’s turn to speak. Speaking to such a large crowd wasn’t particularly new for her; she’d already spoken at two similar events in Frankfort this month. But she recalled a time before she’d been motivated to activism.

“The weeks in between the Marshall County High School shooting and the Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting, I didn’t speak out,” Conner said. “I can’t help but ask myself, if I would have been as selfless and as brave as they were, would this have even happened to them? No time is too soon and no demonstration is too much to save a student’s life.”

Conner’s parents, Troy and Shannon, and her 11-year-old brother stood, watching her from the crowd. As her daughter spoke, Shannon applauded, an unmistakable look of pride on her face.

Cloi Kennedy, a freshman at MCHS, was one of the last students to speak. As she walked toward the podium, the rest of the student speakers gathered around her, holding their signs in the air, looking straight ahead — solemn, straight-faced and serious.

“What time is it?” Kennedy asked.

“It’s time for change,” her peers shouted.

“What time is it?” Kennedy repeated her question.

Holding their signs, the students looked at the crowd defiantly.

They’d made their message clear: For them, it was time for change.