When Houston senior Rahmane Dixon transferred to WKU fall of 2019, she did not expect the harsh realization that she was now a minority. Dixon, with a Black and Hispanic background, transferred from a historically Black college, which she described as the antithesis of WKU.

“Coming here, I kind of forgot what it felt like to be an outsider because I’d been around Black people for two years in a very comfortable, safe space where everyone gets my rhetoric, my jokes, my slang,” she said. “Coming here just reminded me how important it is for people of color, particularly women, to have those safe spaces.”

For Dixon, this transition was the catalyst for the creation of her podcast, “Color Code.” The podcast is a space for women of color to speak their truths without the fear of being misunderstood, something Dixon believes our world lacks, she said.

“The platform is like a virtual space for people in similar situations who don’t really have too many people or too many places to go to to remind themselves that they are important,” she said. “It’s by people who look like you and can give you advice because you know they’ve been through the same thing.”

Dixon said the name of her podcast speaks to the idea of code switching — using a different dialect, accent or language around different groups or in different settings to project a specific identity.

She is still in the first stages of establishing her podcast, but she has created what she calls Mic Me Mondays, where she interviews other women. These women came from relatable backgrounds, an intentional decision Dixon made.

“We can speak our native language to each other, and then we have what I call our ‘business format,’” Dixon said. “I like the idea of women of color just talking to each other in our own coded language.”

Dixon likes to say the podcast is “for women of color by women of color” to emphasize it is a judgement free zone.

“Even though I’m very proud of the progress our world has made — we’re going in a good direction — there’s still little-to-no safe spaces for women of color, who are particularly vulnerable,” she said. “Even in a room full of men, there’s still a gender difference.”

The inspiration not only came from transferring to a predominantly white institution, but it also stemmed from other personal experiences, like the recent loss of her mother.

“Because I felt so alone and isolated, and I had no one to run to anymore, I had to create that space within myself,” she said.

Dixon said everything from the color scheme and pictures to the name of the podcast is authentic to herself. She said it’s her brain brought to life. The hardest part about creating content isn’t finding the ideas, she said, but rather cultivating them into a final product.

“Much of my apprehension is socially based, for being a woman of color comes with eons of trauma and self-doubt,” she said. “However, I hope in time my nerves will be more of a motivator instead of a preventer of my success.”

Similar to Dixon, Tangia Estrada, a podcaster from Denver, amplifies overlooked voices of women in her podcast “That’s What She Did.”

Estrada described it as a show about women, leaders, innovators and rebels “that you probably don’t already know.” The show is two years old and has 91 episodes so far.

Estrada, who identifies as Afro-Latina, said one of the biggest obstacles women of color face in the industry is getting a seat at the table. She said it’s challenging to be seen as valuable in an industry that has a lot of competition.

“One of the things I found through the development of this show is that it’s challenging for people who are on the margins, people who are often overlooked by the mainstream, to first of all see the value of their own story, and then find a way to harness that, to parlay that into more access or more power for themselves and their communities,” she said.

This is a problem she sees frequently as she crowdsources guests to feature on her podcast. She said she receives fewer responses from women of color than white women.

“When I get their pitches, oftentimes, they’re very apologetic,” she said. “The tone is very much, ‘You know, I did this thing, and I’m really proud of it. You’re probably not interested, but I thought I’d tell you because you asked, and I’m sorry for bothering you.’ But they’re really great stories. There’s everyday women out here doing really impactful things in the world that have the potential to not just change their lives or the lives of the people around them, but their entire community.”

Estrada offered Dixon some advice for the “Color Code” podcast.

“You’re going to have to fight for it, and if it’s something that you believe in, then you just keep pushing,” she said. “Draw a coalition, a collective group of people around you, that see your vision and can help you achieve it.”

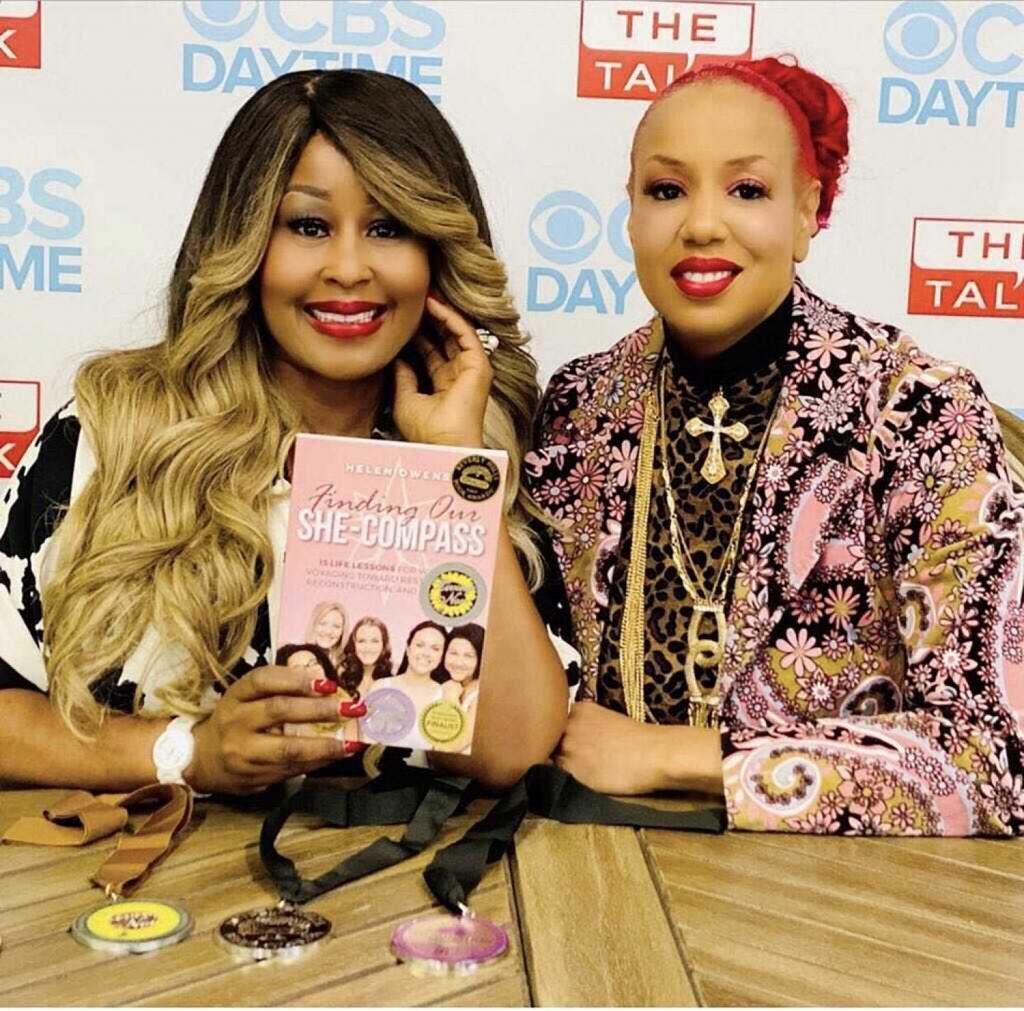

Author Helen Owens from San Francisco said her and her sister’s journey to creating their podcast, “The She-Compass Show,” about women empowerment was incredibly hard.

Owens said it was incredibly hard to be a Black woman and be taken seriously on topics like women’s issues. Women of color, particularly Black women, face the problem of their content being perceived as too rigid for the podcast industry, she said.

“Our frustration is with the audience we’re trying to reach: young women submerged in today’s pop and cancel culture who haven’t had much exposure/experience in positively managing female relationships,” Owens said. “We want to show by example that Black women are elegant and refined while simultaneously sharing messages of positivity with all women. But because we as Black female hosts are pigeon-holed into the assumption that ‘Black people should only focus on Black issues,’ we continue to have challenges growing our audience.”

Owens said the majority of the backlash she faced in the industry came from fellow Black women, who said they did not believe she or her platform were “Black enough.” She said all people, regardless of race, have expectations concerning her vocal delivery and diction — how she’s supposed to sound on air.

The sisters decided to take an ongoing sabbatical as they rebrand their podcast in order to grow their audience. While they currently aren’t recording episodes, the sisters are reaching out to new listeners.

Owens wants to set an example for younger generations of Black women like Dixon so that they can know that they do not have to “clown around” in order for themselves, their work and their platforms to be respected.

Owens said Black women entering the podcast industry, including Dixon, should be persistent and dedicated, but should know that the journey isn’t easy and will probably come with a lot of tears.

“I think at one point if enough of us get to the point where we demand to be taken seriously like anyone else … we’re going to make a breakthrough.”

For Washington D.C. natives Dr. Lanre Falusi and Dr. Lisa Varghese-Kroll, the journey to creating their podcast was long coming. The two met in their first semester of college in 1997, and their friendship stood the test of time through medical school, residency and starting their own families.

Their podcast, “Hippocratic Hosts,” is a medical based show that discusses health, family and balancing life. The name itself is in reference to the Hippocratic oath, the ethics code of physicians.

“The topics we’ve covered have been everything from raising kids in the COVID-19 pandemic, to talking about race and racism, to our favorite books for both kids and adults and environmental justice,” Falusi said. “There’s always some way to connect current events or these big issues back to health, and we feel that’s a topic that’s appealing to a lot of people.”

Falusi said one of her and Varghese-Kroll’s objectives is to dispel health and medical myths.

One such myth deals specifically with the damaging medical assumption that Black people have a higher pain tolerance threshold than white people. Their podcast episode “Blame It On the Pain: Pain Management 101” discusses “how Black patients historically have been treated inequitably and made to feel that they are exaggerating their level of pain.” Episodes eight and nine detailed race and how it affects people’s experiences in the healthcare industry.

Falusi described herself as being from “somewhere between Nigeria and Chesterfield, Virginia” while Varghese-Kroll has Indian heritage and is originally from Toronto. Their identities have been key motivators in doing their podcast.

“We’re not media moguls,” Varghese-Kroll said. “We don’t come from places with tremendous connections, and sometimes that goes along with being a person of color. Often in this society it is the Black and brown communities that may not have that sort of social capital.”

Women of color in the podcast industry face obstacles such as a lack of resources as well as their shows being categorized as “niches,” Varghese-Kroll said. She said the idea behind this is that a person may view a piece of podcast cover art featuring people of color on it and think to themselves that the show solely caters towards people of color when that may or may not be true. While not every podcaster wants a large audience, the fear of being categorized as a “niche” show is very real for women of color podcasters who aim for a broad, inclusive audience.

The podcast industry is diversifying, but like many industries, it still has a ways to go until the glass ceiling that leaves women of color on the outskirts of success is broken.

“The only way to normalize representation is to have representation,” Varghese Kroll said. “We have to have people breaking barriers if barriers exist.”

Both doctors commended Dixon’s efforts to establish a place for women of color on WKU’s campus.

“If you are not a person of color, you may genuinely have no idea that code switching, or the absence of a space for you, that those things exist,” Varghese-Kroll said. “I think she’s really doing a service, and it’s hard because when you’re one of the only people doing a service, the supports aren’t necessarily in place for you.”

Dixon said “Color Code” has caused her to reframe how she sees the women around her.

“I am prone to communicate now,” Dixon said. “I don’t look for differences. I now see the similarities and think deeply about those around me. ‘Color Code’ has completely changed my life, in and outside of school, for the better.”

Falusi said Dixon should think of all the women of color in the podcast industry who will come behind her who may not have been able to if she hadn’t created that space.

Dixon has big dreams for the future of “Color Code,” but for now, she said her greatest impact is the followers of her podcast themselves.

“My greatest impact thus far are the private messages I get of people who are deeply appreciative of what I was doing when I was doing it consistently, when it first launched,” she said.

Eventually, Dixon hopes to launch seminars through “Color Code” and create an online blog that expands from its Instagram and Facebook pages. She said despite the obstacles of being a woman of color in the industry, she doesn’t feel threatened because voices of color are becoming more prevalent.

“As a multi-racial woman, I find I bring a new, fresh perspective on the world,” she said. “I believe the audible world is ready for that.”