For those struggling with an eating disorder, the path to recovery may be hard to find. For women of color, the chance to receive help for their eating disorders may be affected by cultural barriers and medical biases.

Wife, mother and author Achea Redd from Columbus, Ohio said via email she was able to hide her eating disorder for the majority of her life due to being a larger sized, Black American woman.

“Unfortunately, I’ve been able to fly under the radar for the majority of my life because I’ve always been ‘normal’ weight and considered healthy,” Redd said. “I’m not what the books show that someone with an eating disorder would look like.”

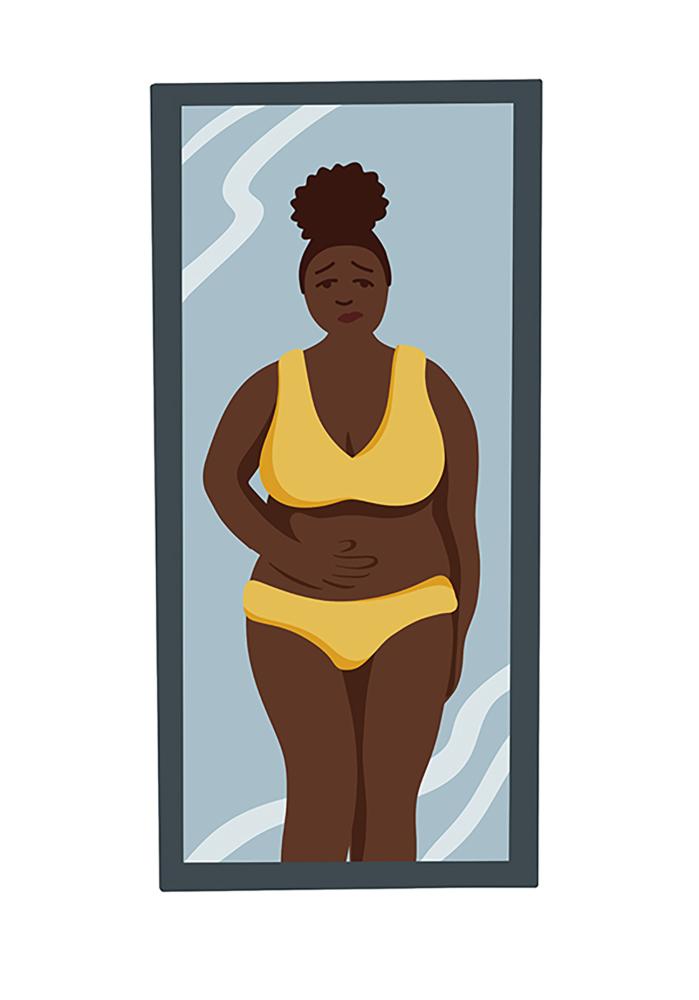

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, the image of a person living with an eating disorder has been historically associated with young, white women despite the mental condition affecting people from all ethnic demographics at similar rates.

The National Eating Disorders Association also found that people of color are less likely than their white peers to be asked by their doctors about their disordered eating symptoms. Additionally, African Americans in particular were significantly less likely to receive help for their eating issues.

Redd said being a woman of color impacted her experience in getting help, as medical professionals formed their medical opinions based solely on the Body Mass Index scale and the numerical value of her body weight.

“They have never asked me about my relationship with food,” Redd said.

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, doctors exhibit medical bias in determining whether women of color have symptoms of disordered eating and recommending they seek help for their eating disorders.

In one research study, medical officials were presented with identical case studies concerning a fictional patient named “Mary” with disordered eating symptoms. The only difference was her race. While 44% of the doctors involved in the study considered the white woman’s behavior with food to be problematic and 41% considered the Hispanic woman’s behavior problematic, only 17% considered the Black woman’s behavior in regards to food to be problematic.

The study also found that clinicians were less likely to recommend that the Black woman should receive professional help.

The results of the study fell in line with Redd’s experiences with medical professionals.

“There is this assumption I needed to eat less and move more, but they’ve always been surprised to find out that I exercise three to four times a week, and that I don’t really eat enough,” Redd said.

Redd said these assumptions have been very damaging to her recovery journey. She said it wasn’t until she found a nutritionist that someone acknowledged that she could be undereating.

“She wasn’t concerned about me having too much; she was concerned about me having too little,” Redd said. “That was a game changer for me. For the first time, I felt seen.”

College junior Sydney Owens from Nashville, who declined to provide the name of her university, said via email that her physical appearance contributed to her development of disordered eating habits.

“Being a Black woman from the South who has been fat my whole life, it was expected of me to change how I look, or ‘get worse’ — become larger — and die,” Owens said.

Owens said she developed an eating disorder in part due to bullying.

“I developed an eating disorder when I was nine and entered a middle school, a white one where being thin and white or thin and another race were the things people honored,” Owens said. “I was bullied into wanting to change how I looked.”

Redd said the difference in beauty standards among ethnic cultures contributes to women of color developing eating disorders.

She said in the Black community, women are “inundated” with images of small waists and big butts in rap videos.

“To achieve that, we do obscene amounts of squats, corsets, and waist train to achieve figures that may not even be our natural build,” Redd said. “Additionally, we tend to resort to the coveted yet dangerous BBL (Brazilian Butt Lift) or butt injections for a more permanent fix.”

She said these are all “subtle” ways that eating disorders show themselves within the Black community.

Vanessa Johnson, a sophomore at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga from Nashville, said the existence of physical stereotypes like big breasts in the Black community made it hard for her growing up, as she didn’t fit this image since she was “petite.”

Johnson said her family would tell her she shouldn’t try to get any bigger and that she’d naturally develop a curvier body type over the years.

“Whenever I would try to eat more, they would be like, ‘Oh no, you don’t need it. It’ll just come natural,’ and it hasn’t. So it kind of made me stop eating for a while,” Johnson said.

Owens said being a woman of color contributed to her not receiving help for her disordered eating habits.

“Being from a Black home, things like eating disorders (and) depression aren’t expected of us,” Owens said. “We are supposed to take the challenges of mental illness — usually called ‘life’ or ‘trials and tribulations’ — with pride and just push forward.”

Owens said she’s been trying to help herself through her eating disorder but would like to see a doctor soon.

“I’d definitely like to see a doctor about it sometime soon, but even though I have got insurance, I can’t really afford it (because of) racial disparities in healthcare costs and income inequality.”

Owens said there are cultural barriers within communities that contribute to Black women, specifically, developing eating disorders.

“Eating disorders are commonplace among white peers, and their body issues don’t stay their own,” Johnson said. “They explode all over everyone, especially fat individuals.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, the presence of eating disorders among women of color may be a partial response to environmental stress and factors like abuse, racism and poverty. The organization said that women of color may be more vulnerable to eating disorders compared to their white peers as a result.

For Owens, the desire to change her physical image through disordered eating came from cultural factors as well.

“There is also the cultural stigma that largeness equals masculinity, so on top of being masculinized as a Black girl, so was my body,” Owens said.

For Johnson, she said being around the curvy women in her family combined with the media’s perpetuation of an image “stereotype” revolving around women of color contributed to her eating disorder.

At one point during her freshman year of college, she weighed 88 pounds.

“Most of the time we’re all big boned and thicker than most,” Johnson said. “It was just kind of hard looking at myself seeing how small I am because I’m really petite.”

Johnson said she never wanted to talk to anyone about her eating disorder because of responses from her family, therapist and doctor.

“I felt like people didn’t understand what I was going through and didn’t see it,” Johnson said. “It’s like I really can’t ask for help and get the help I need.”

Johnson said she feels social media and the presence of “Instagram baddies,” social media influencers who are “thick” and have “slim waists,” is a cultural factor that contributes to women of color developing eating disorders.

“Most of the time it’s not natural,” Johnson said. “It’s just that that’s what everyone sees, and that’s what everyone likes now.”

Johnson said she doesn’t think people understand that there are different types of eating disorders and that the disorders and their victims can’t be lumped together.

“They don’t really see that it could be overeating and it can be undereating. It could be stress eating,” Johnson said. “Eating disorders are (a) very wide range, so you can’t put everybody in one category.”

Owens said she believes women of color face a barrier due to their race when seeking medical help for eating disorders because of “stigma.”

“The medical stigma that we don’t feel pain or feel as much pain as our white counterparts is deeply ingrained into the medical field,” Owens said.

Owens said the amount of representation given to white women compared to Black women with eating disorders contributes to the difficulty women of color face in getting help for their mental health troubles.

“The over-representation of white women with eating disorders also definitely contributes to Black women and women of color not being heard fully when there is a medical or mental issue,” Owens said.

Owens said another factor that contributes to women not receiving help for their eating disorders are assumptions that larger-bodied women with eating disorders have a binge-eating disorder while thinner women with eating issues are automatically considered anorexic.

“If you mention thinking you may have an eating disorder, especially if you’re already in a larger body, people assume you’ve got binge-eating disorder,” Owens said. “That assumption drives an anorexic person who has not received help into a further spiral of thinking they are still eating too much.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, exact statistics on the prevalence of eating disorders among women of color are “unavailable” due to the “historically biased view that eating disorders only affect white women.”

The Association advocates for medical professionals to re-examine their assumptions about the appearance of eating disorder victims and increase their awareness of factors affecting minority populations.

Redd said there are racial genetic differences that have to be taken into account when medical professionals decide who has and who doesn’t have an eating disorder.

“We have to stop judging people based off of externals,” Redd said.

Redd said her advice for women of color struggling with eating disorders is to get help.

“Resist diet culture and the lies social media tries to feed you,” Redd said. “Use your voice.”