This story was originally published in late November in “Power,” the third issue of Talisman magazine.

Editor’s note: This piece reflects upon instances of abuse and PTSD.

Any day, any time

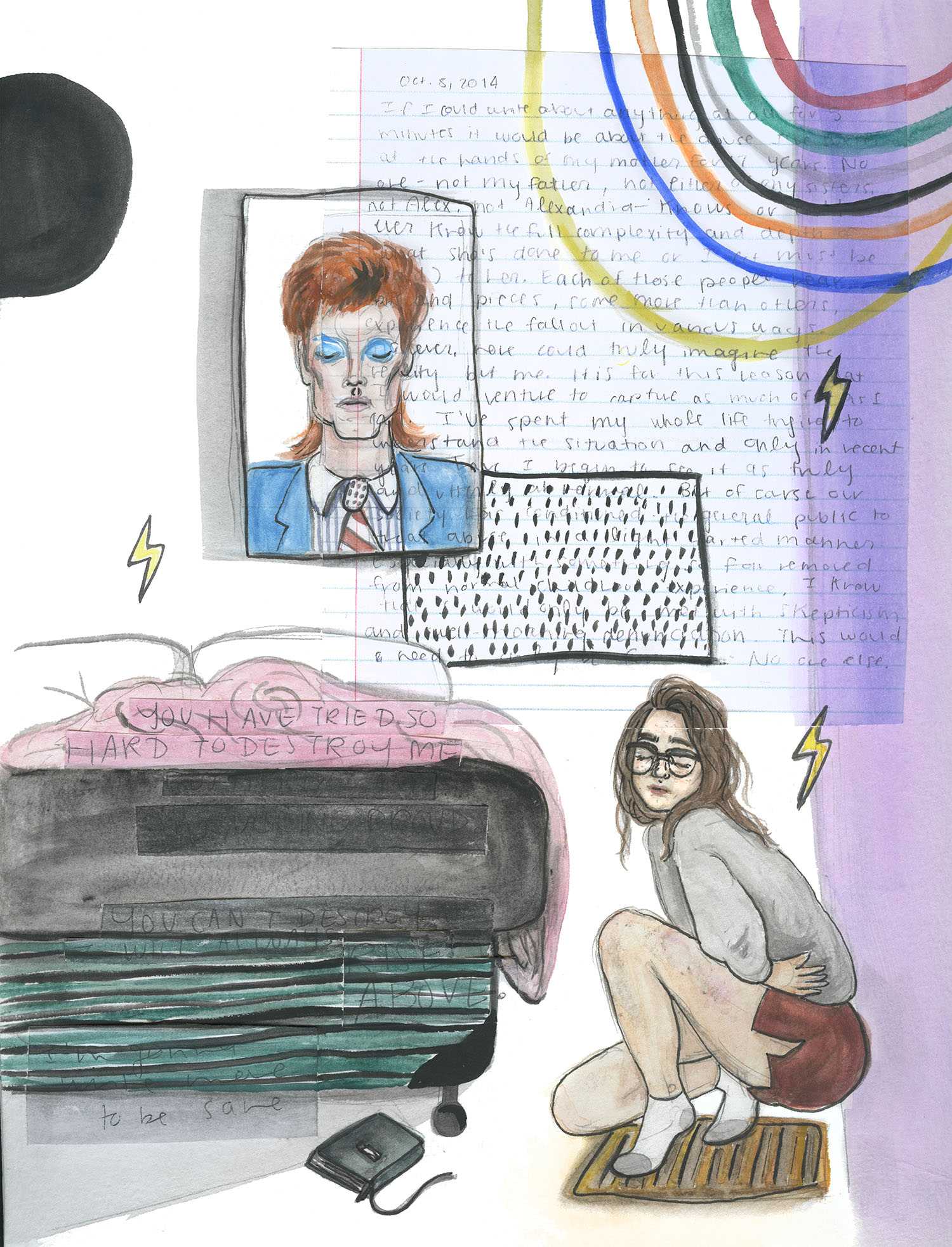

I am sitting on the floor between my bed and the wall, right on top of the bronze heater grate where I feel safest. Safe is, of course, a relative term in a house so hostile.

The air warms my thighs, almost to the point of burning. The grate presses a red grid onto the palms of my feet. I am only dully aware of the physical sensations of heat and metal and carpet and wall. The rest is my numb, fuzzy head, stinging eyes, ringing ears and a bruise forming on my thigh. I don’t remember how I got it.

It could be any day. It could be any time.

I try to write in my journal, but I can already feel memories of the event begin to dissipate. I find myself unable to reconstruct the last few hours. How did it even start this time? How does it usually start? I can’t remember. Why can’t I remember? All I know is that I’m numb. Numb, numb, numb. I’m numb, and I’m tired, and I have school in the morning.

December 2013

The first time I felt post-traumatic stress disorder, I was sitting in a school assembly listening to a speaker who lost her arm in a car accident involving a drunk driver. Her gravelly voice became animated and loud as she pleaded for us to think before we drove home from a party after a few beers. The amplified booming of her voice made me feel like I wasn’t in my head. It made me feel like I was a kid again. Like I was sitting on the heating grate in my room.

When I told a friend about it later, she told me I was overreacting. No one else seemed bothered by it, she said. It wasn’t that loud.

Trauma is challenging to write about for reasons you might not expect. It’s not because the memories are difficult; it’s because the memories are often not there.

The nature of trauma is such that your brain wants it gone. It’s too painful to process and store, so your brain buries it — deep. Without the prompting of diary entries or other triggers, I don’t remember a lot of the hard parts of my childhood.

Because of this, I often told myself I didn’t need help with what happened to me. Why did I need help with something I couldn’t remember?

Besides, PTSD was for war-torn soldiers. PTSD was waking up from nightmares of cascading bullets so real you can feel the shrapnel. It was too grand for the panicked fog I felt when I heard an aggressive scream or saw a parent yank their child’s wrist in the grocery store. It was far too heroic for the feeling of being buried in my head whenever I felt out of control. No, that was simply my inability to handle things.

![]() January 2016

January 2016

The second time I feel it will be years later. This time, it is a different beast entirely.

I’m 18 now. I hardly think about it at all if I can help it.

It’s a Monday and I awake before most of the world for my 6 a.m. shift at the coffee shop where I work as a barista.

As I scroll through the news on my Twitter feed, I begin to see references to the death of David Bowie. Daylight is breaking outside on a cold January morning. White sunlight reflects off the recent snow, making the whole world seem blinding. It’s too white. It’s too cold.

I’m jealous of anyone who is still asleep and doesn’t yet know that they live in a world without David Bowie. Later on this same day as I reflect on the death of my hero, I come to realize I do not believe in an afterlife.

This day, Jan. 11, 2016, marked the beginning of the worst bout of mental health issues I’d ever experienced. For the first time in my life, I fully comprehended that I was going to die, and there was nothing I could do about it.

I’m far from naive enough to believe I’m the only person to ever suffer this sort of existential crisis. I knew this, yet the fear was paralyzing. For the rest of that winter going to work was hard. My hands shook and spilled steamed milk when I poured lattes. I couldn’t bring myself to work the register because I couldn’t muster a facade of congeniality. My nightmares were constant and volatile.

March 2016

I finally admit to myself that I’m sick.

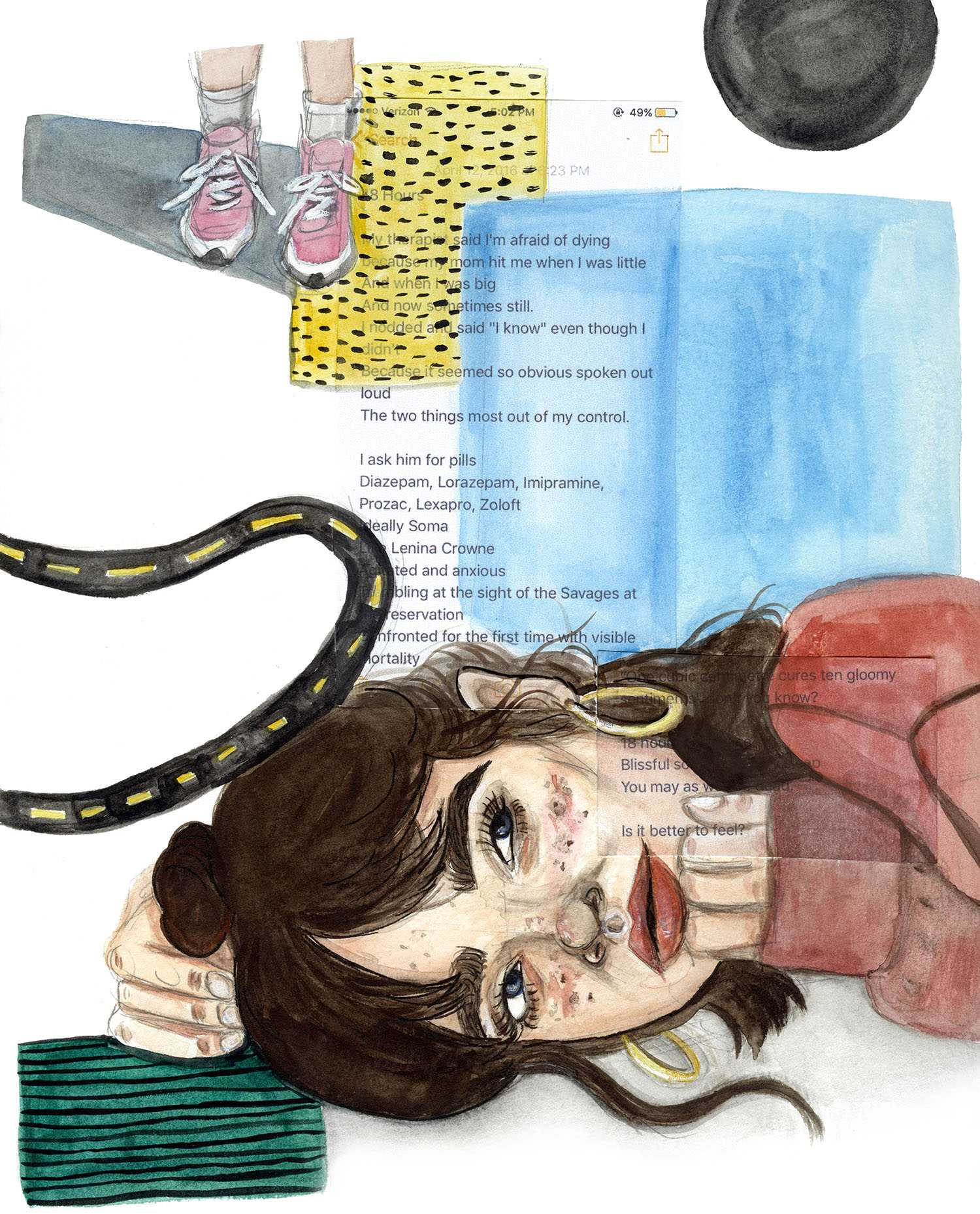

I tell my new therapist about how my heart beats fast all the time and how I can’t stand to be alone because my thoughts race and spiral until I feel like I’m suffocating. I tell him that sometimes I get so scared I don’t feel like I’m really there.

He says triggers can be strange and unpredictable. I learn that for me, triggers can come in the form of anything that makes me feel powerless.

Powerlessness.

I recognize it as that sitting-on-the-heater-grate feeling.

He says death triggers me because it’s the ultimate form of disempowerment. He says it’s because abuse takes all your power away, and death does too.

January 2017

It is nearly a year later. There is a police officer putting my glasses back on my face and another putting handcuffs on my arms. One of them asks if I remember what happened. He asks if I meant to hurt myself. I say I don’t know, that I can’t remember. My head is foggy.

That night, I lie in a hospital bed in the emergency psychiatric ward wearing a papery hospital gown and non-slip socks with a blue blanket made of thin, coarse fabric. The ward is cold but the socks are warm. A psychiatrist calls my name. She says they’re going to give me an assessment to see if I need to be transferred to an inpatient facility.

I can’t answer any of her questions, because I can’t remember. Finally, she asks me if I really wanted to die. I tell her no, because I’m afraid of death. She asks if I tried to hurt myself because I wanted to regain control. Because I felt powerless to fix the situation. I tell her yes.

Later, I learn that Khloe Kardashian has a new show called “Revenge Body” that apparently only airs in dismal hospital waiting rooms at 4 a.m. I remember I was supposed to start marathon training that week. I suddenly have the wherewithal to realize that I’m fucking miserable.

Three days later, it’s Sunday. I step into a gray January morning and lace up my running shoes. My frozen fingers fumble with the laces, but I’m too exhausted to properly feel the cold. My eyes still sting; my head is still fuzzy; and my whole body is still sore. I haven’t trained. I haven’t run in months. But it doesn’t matter. I step onto the road and start to run.

May 2017

It has been 18 weeks exactly: the amount of weeks it takes to train for a marathon. I turn a corner on Eastern Avenue to see a white banner that reads “MILE 21.” I’ve been waiting four hours through the pain to turn this corner to see my sister, Megan. She joins me to run the last five miles of my second marathon. My head is foggy with adrenaline. I’m duly aware of the soreness in my legs from working them for hours, and my ears are ringing from the cheering crowd on the sidelines. The Cincinnati skyline is just on the horizon — five miles away.

Every second I want to stop, I remind myself of how it felt to spend a sleepless night in a hospital bed with a thin blanket and non-slip socks. I remember the heater-grate feeling. It pushes me forward.

I feel proud.

I feel powerful.

Damage Control

This story was originally published in late November in “Power,” the third issue of Talisman magazine.

Editor’s note: This piece reflects upon instances of abuse and PTSD.

Any day, any time

I am sitting on the floor between my bed and the wall, right on top of the bronze heater grate where I feel safest. Safe is, of course, a relative term in a house so hostile.

The air warms my thighs, almost to the point of burning. The grate presses a red grid onto the palms of my feet. I am only dully aware of the physical sensations of heat and metal and carpet and wall. The rest is my numb, fuzzy head, stinging eyes, ringing ears and a bruise forming on my thigh. I don’t remember how I got it.

It could be any day. It could be any time.

I try to write in my journal, but I can already feel memories of the event begin to dissipate. I find myself unable to reconstruct the last few hours. How did it even start this time? How does it usually start? I can’t remember. Why can’t I remember? All I know is that I’m numb. Numb, numb, numb. I’m numb, and I’m tired, and I have school in the morning.

Advertisement

December 2013

The first time I felt post-traumatic stress disorder, I was sitting in a school assembly listening to a speaker who lost her arm in a car accident involving a drunk driver. Her gravelly voice became animated and loud as she pleaded for us to think before we drove home from a party after a few beers. The amplified booming of her voice made me feel like I wasn’t in my head. It made me feel like I was a kid again. Like I was sitting on the heating grate in my room.

When I told a friend about it later, she told me I was overreacting. No one else seemed bothered by it, she said. It wasn’t that loud.

Trauma is challenging to write about for reasons you might not expect. It’s not because the memories are difficult; it’s because the memories are often not there.

The nature of trauma is such that your brain wants it gone. It’s too painful to process and store, so your brain buries it — deep. Without the prompting of diary entries or other triggers, I don’t remember a lot of the hard parts of my childhood.

Because of this, I often told myself I didn’t need help with what happened to me. Why did I need help with something I couldn’t remember?

Besides, PTSD was for war-torn soldiers. PTSD was waking up from nightmares of cascading bullets so real you can feel the shrapnel. It was too grand for the panicked fog I felt when I heard an aggressive scream or saw a parent yank their child’s wrist in the grocery store. It was far too heroic for the feeling of being buried in my head whenever I felt out of control. No, that was simply my inability to handle things.

The second time I feel it will be years later. This time, it is a different beast entirely.

I’m 18 now. I hardly think about it at all if I can help it.

It’s a Monday and I awake before most of the world for my 6 a.m. shift at the coffee shop where I work as a barista.

As I scroll through the news on my Twitter feed, I begin to see references to the death of David Bowie. Daylight is breaking outside on a cold January morning. White sunlight reflects off the recent snow, making the whole world seem blinding. It’s too white. It’s too cold.

Advertisement

I’m jealous of anyone who is still asleep and doesn’t yet know that they live in a world without David Bowie. Later on this same day as I reflect on the death of my hero, I come to realize I do not believe in an afterlife.

This day, Jan. 11, 2016, marked the beginning of the worst bout of mental health issues I’d ever experienced. For the first time in my life, I fully comprehended that I was going to die, and there was nothing I could do about it.

I’m far from naive enough to believe I’m the only person to ever suffer this sort of existential crisis. I knew this, yet the fear was paralyzing. For the rest of that winter going to work was hard. My hands shook and spilled steamed milk when I poured lattes. I couldn’t bring myself to work the register because I couldn’t muster a facade of congeniality. My nightmares were constant and volatile.

March 2016

I finally admit to myself that I’m sick.

I tell my new therapist about how my heart beats fast all the time and how I can’t stand to be alone because my thoughts race and spiral until I feel like I’m suffocating. I tell him that sometimes I get so scared I don’t feel like I’m really there.

He says triggers can be strange and unpredictable. I learn that for me, triggers can come in the form of anything that makes me feel powerless.

Powerlessness.

I recognize it as that sitting-on-the-heater-grate feeling.

He says death triggers me because it’s the ultimate form of disempowerment. He says it’s because abuse takes all your power away, and death does too.

January 2017

It is nearly a year later. There is a police officer putting my glasses back on my face and another putting handcuffs on my arms. One of them asks if I remember what happened. He asks if I meant to hurt myself. I say I don’t know, that I can’t remember. My head is foggy.

That night, I lie in a hospital bed in the emergency psychiatric ward wearing a papery hospital gown and non-slip socks with a blue blanket made of thin, coarse fabric. The ward is cold but the socks are warm. A psychiatrist calls my name. She says they’re going to give me an assessment to see if I need to be transferred to an inpatient facility.

I can’t answer any of her questions, because I can’t remember. Finally, she asks me if I really wanted to die. I tell her no, because I’m afraid of death. She asks if I tried to hurt myself because I wanted to regain control. Because I felt powerless to fix the situation. I tell her yes.

Advertisement

Later, I learn that Khloe Kardashian has a new show called “Revenge Body” that apparently only airs in dismal hospital waiting rooms at 4 a.m. I remember I was supposed to start marathon training that week. I suddenly have the wherewithal to realize that I’m fucking miserable.

Three days later, it’s Sunday. I step into a gray January morning and lace up my running shoes. My frozen fingers fumble with the laces, but I’m too exhausted to properly feel the cold. My eyes still sting; my head is still fuzzy; and my whole body is still sore. I haven’t trained. I haven’t run in months. But it doesn’t matter. I step onto the road and start to run.

May 2017

It has been 18 weeks exactly: the amount of weeks it takes to train for a marathon. I turn a corner on Eastern Avenue to see a white banner that reads “MILE 21.” I’ve been waiting four hours through the pain to turn this corner to see my sister, Megan. She joins me to run the last five miles of my second marathon. My head is foggy with adrenaline. I’m duly aware of the soreness in my legs from working them for hours, and my ears are ringing from the cheering crowd on the sidelines. The Cincinnati skyline is just on the horizon — five miles away.

Every second I want to stop, I remind myself of how it felt to spend a sleepless night in a hospital bed with a thin blanket and non-slip socks. I remember the heater-grate feeling. It pushes me forward.

I feel proud.

I feel powerful.