This story was originally published in early May in “Grit,” the fourth issue of Talisman magazine.

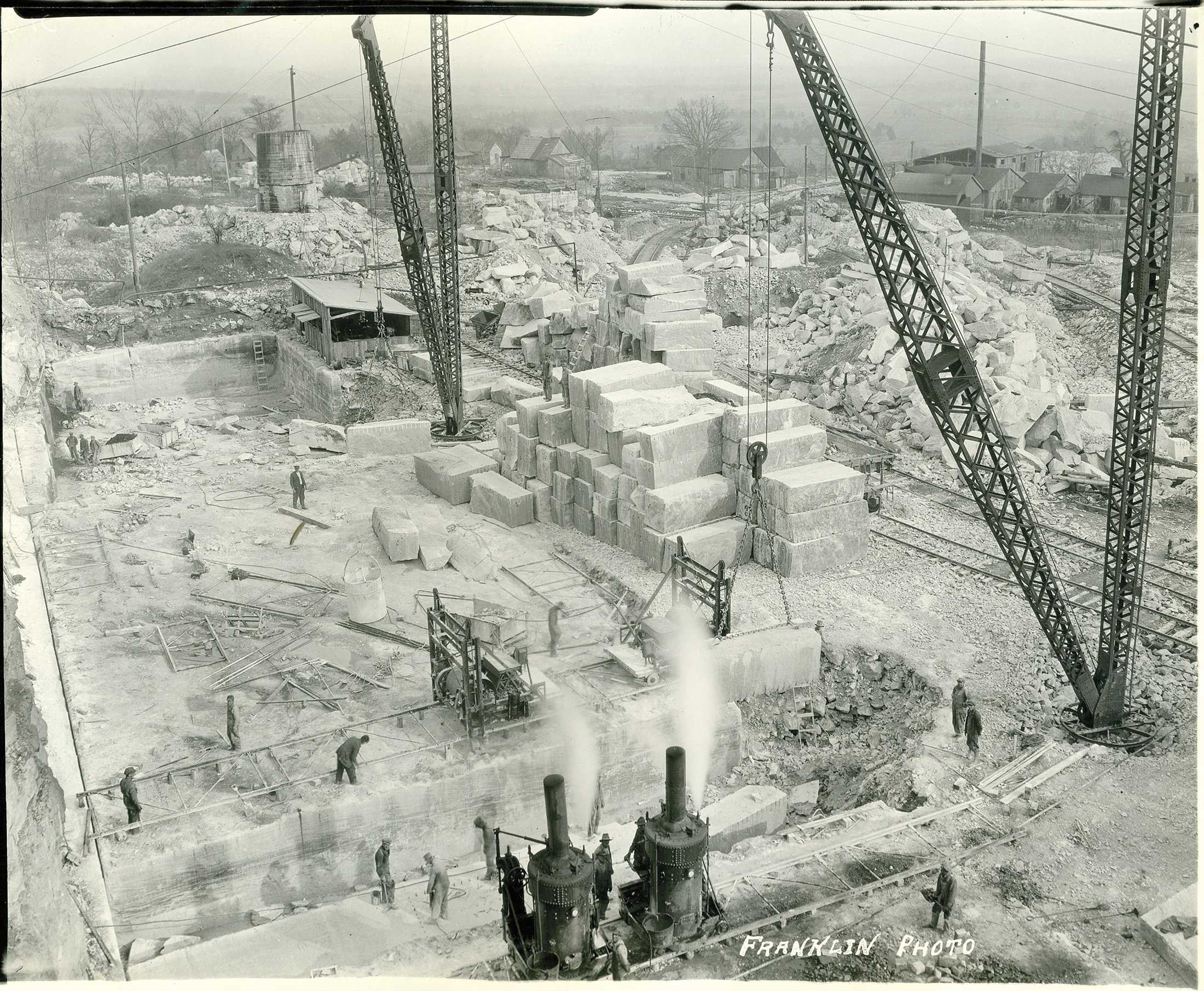

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n the beginning, ox-driven carts hauled slabs of stone down single-lane dirt roads. Suspenders and hats in place, men were poised for another day of work. They walked alongside the carts as the team drudged for miles — wooden wheels creaking with each step.

Able to withstand 3,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, those slabs were not traveling to ordinary construction sites. With each stone, quarrymen were erecting legacies.

Within a few decades, places like downtown Bowling Green and WKU would be unrecognizable — transformed by the impact of local limestone quarries.

From the 1830s to the 1930s, limestone from Bowling Green dominated Warren County construction. Bowling Green stands on a 50-mile bed of oolitic limestone, but, in the early 19th century, the city was unaware of the stone’s quality, worth and utility.

However, Bowling Green native John Howarth seized an opportunity, purchased land for $20, and established the White Stone Quarry in 1833.

As production began, the stone was praised for its strength and coloration, winning competitions against Ohio Buena Vista Freestone, Joliet Limestone and Bedford Limestone. The White Stone Quarry president often claimed that the oolitic limestone was even fire-resistant.

In 1839, the earliest building made from the quarry’s limestone was set in place on the downtown square: old Citizens National Bank. When the bank caught fire in 1984, the fire-resistant claims were confirmed, for nothing was left but the original limestone framework from White Stone Quarry.

Howarth and his men worked the quarry for 23 years, hauling the stone for miles by cart over country roads, yet the deed traded hands over several decades. As America met an era of industrialization and railroad systems, a corporation intercepted and established a permanent legacy, rebranding the quarry operation as the “Bowling Green White Stone Company” in 1905.

In 1906, the early framework of WKU began to take shape, and President Henry Hardin Cherry planned to take full advantage of oolitic limestone’s beauty and strength.

An expert on the origin and architecture of WKU’s campus, Library and Special Collections department head Jonathan Jeffrey penned articles on Cherry’s interests in education and architecture.

“Henry Hardin Cherry was determined to build a beautiful, immense, classically-influenced temple at the top of the Hill,” Jeffrey said. “He wanted WKU’s temple to be one of knowledge and academia.”

Despite Cherry’s wishes, the Public Works Administration forced architect Brinton B. Davis to outsource Cherry Hall’s limestone from Indiana due to local production and material costs. The PWA felt that using “Bowling Green stone” was uneconomical. So, architects were forced to use Bedford Limestone instead.

However, Cherry and Davis later incorporated local industry into WKU construction, conforming with construction trends in downtown Bowling Green and nationwide.

Until the Great Depression, the Bowling Green White Stone Company continued to provide material to downtown and university construction sites, as well as national sites in New York, Missouri and Ohio — to name a few.

Locally, First Baptist Church, the Houchens Industries headquarters, the Warren County Courthouse and the Van Meter Hall columns all contain oolitic limestone from White Stone Quarry. The stone for the Kentucky Building columns — hauled from the northeast side of White Stone Quarry Hill — marked the final project for the Bowling Green White Stone Company.

Unable to recover from the economic hardships of the Great Depression, the Bowling Green White Stone Company ceased production, and the White Stone Quarry closed. It now remains untouched, sealed behind a padlocked gate.

Much of this history would have remained unrecorded if a curious WKU history major had not pursued the information in the 1980s.

Christy Spurlock grew up on L C Carr Road in Bowling Green, adjacent to the old White Stone Quarry. While attending WKU in the 1980s, she decided to dig deeper into the quarry’s history in an effort to write an original research paper. Spurlock is now the Kentucky Museum education curator, and her research has become the primary resource on the history of White Stone Quarry, including for this story.

“I had visited the abandoned quarry ruins and knew that some of the neighborhood families had relatives who had worked there,” Spurlock said. “But, like most self-absorbed 20 year olds, I had no sense of the significance of the quarry to the neighborhood, county and state.”

In 1984, she partnered with a former quarryman, her 75-year-old neighbor Roscoe Alford. Together, they uncovered and recorded the history of White Stone Quarry.

With Alford’s help, Spurlock was able to interview a variety of individuals whose family members had worked and lived on the quarry grounds during the pinnacle of its success.

“As I listened and questioned Mr. Alford and the others, looked through photographs and researched deeds and maps, this fascinating picture began to emerge for me of this once-thriving business and the lasting impact it had on my community,” Spurlock said.

During the 1920s, White Stone quarrymen were paid 30 to 40 cents an hour, working six full days one week and five and a half days on alternate weeks. They clocked in at 6:30 a.m. and clocked out at 5 p.m., with a steam whistle signaling a 35-minute lunch break at noon.

While reviewing interviews and research, Spurlock realized that the hard work was an endless sense of pride for the quarrymen.

“Working in White Stone was a physically hard way to earn a living,” Spurlock said. “But, every man took pride in his product. Years later, they could walk through town or campus, point at a building and smile at the fact that they had helped construct it. Their work had true value.”

However, White Stone Quarry was only one of as many as 22 quarries in Bowling Green that cut and distributed limestone throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

About 10 miles northwest of downtown Bowling Green, on the banks of the Gasper River, stood the remains of another, much smaller operation: Caden Quarry.

Since the 1930s, Caden Quarry had been owned by the Swetmon family. Shelby (S.V.) Swetmon purchased the land from the Caden family around 1933, and, in the 1960s, S.V. and his two brothers separated the land among themselves.

As of 2018, David Swetmon, S.V.’s son, protected the remnants of the abandoned quarry.

Barbed wire disconnected visitors from the center of Caden Quarry, discouraging trespassers from destroying the historic site or vandalizing the property. Ferns and poplar trees reclaimed the machinery and remaining stones, marking almost a century of inactivity.

It was apparent that around 1930 production had simply ceased.

Like White Stone Quarry, Caden Quarry’s business had been gravely impacted by the Great Depression and the burgeoning concrete block industry. In addition, the PWA had voiced concerns about encroachment on the limestone formation’s stability.

In its prime, Caden Quarry had routinely floated limestone slabs down the Gasper River, redirecting those slabs to the Barren River and later delivering them to the Southern Cut Stone Company on Church Street.

“I can’t imagine being down here when production was in full swing,” Swetmon said. “For that day and time, the technology had to be advanced. The workers had to have been proud to work here.”

Smaller quarries, like Caden Quarry, provided limestone for slighter, concentrated projects in the Bowling Green area. As slabs from White Stone Quarry were polished for the Warren County Courthouse, Caden Quarry stone was prepared for nondescript ornamental facets, borders and cupolas.

At the height of production, Caden Quarry employed around 50 quarrymen. A department store, a foreman’s home, a dynamite cavern and 15 homes were also present in the area.

However, like the majority of Bowling Green’s quarrymen, Caden Quarry’s employees were forced to find other means of income after the Great Depression.

Several decades later, in the 1960s, S.V. Swetmon intended to begin crushing the limestone rubble left from production. He had purchased the necessary equipment and voiced his plans to his family and friends. “He figured out pretty fast that the rock-crushing idea wasn’t going to work out,” Swetmon said. “

It turned out to be a bigger job than he expected, so he left it alone.”

As history slowly disintegrated, owners of Bowling Green’s abandoned quarries faced decisions about whether or not to resume production. The limestone material was still viable, and technology had vastly improved.

Owners like David Swetmon appreciated the history that they owned and were determined to protect it, but they have been uninterested in resurrecting the industry.

“People keep telling me to open it back up,” Swetmon said. “I just don’t have any interest in it. I like the quarry — the area — the way it is now.”

Bowling Green’s limestone production was fated to become a chapter in history, yet its impact has been long-lasting. Oolitic limestone had created an incomparable legacy that generations of Bowling Green residents would treasure for centuries to come.