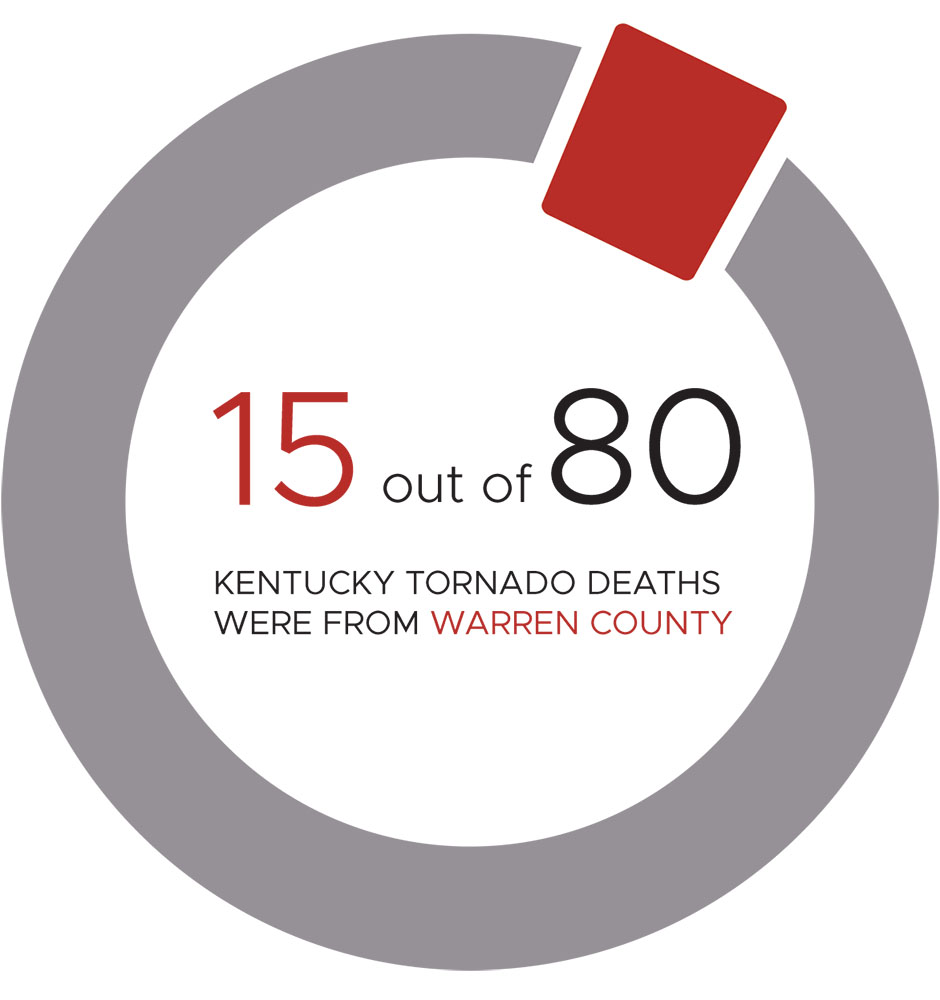

The impact of the tornado on Friday, Dec. 10, 2021 solidified that night as one to remember in Kentucky history. The natural disaster caused unprecedented damage to western Kentucky, flattening neighborhoods and killing 80 people.

What ensued in the weeks that followed the tornado was a testament to the strength of Kentucky’s communities like the Warren County School System, which played a part in helping victims regroup.

In Warren County, 15 people died due to the tornado, according to a press release from the office of Governor Andy Beshear. The natural disaster destroyed at least 500 homes and 100 businesses in the county, according to WKU Public Radio.

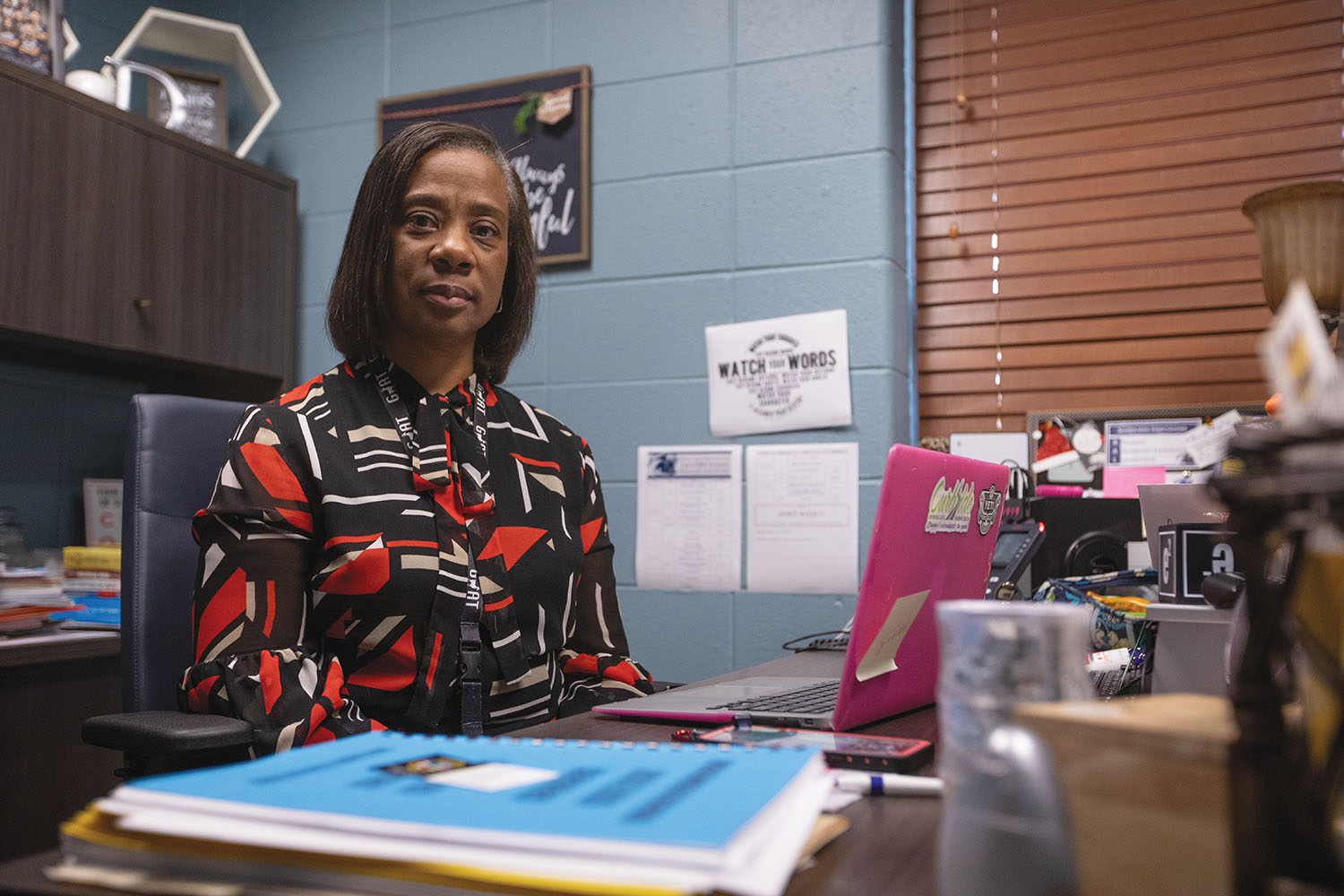

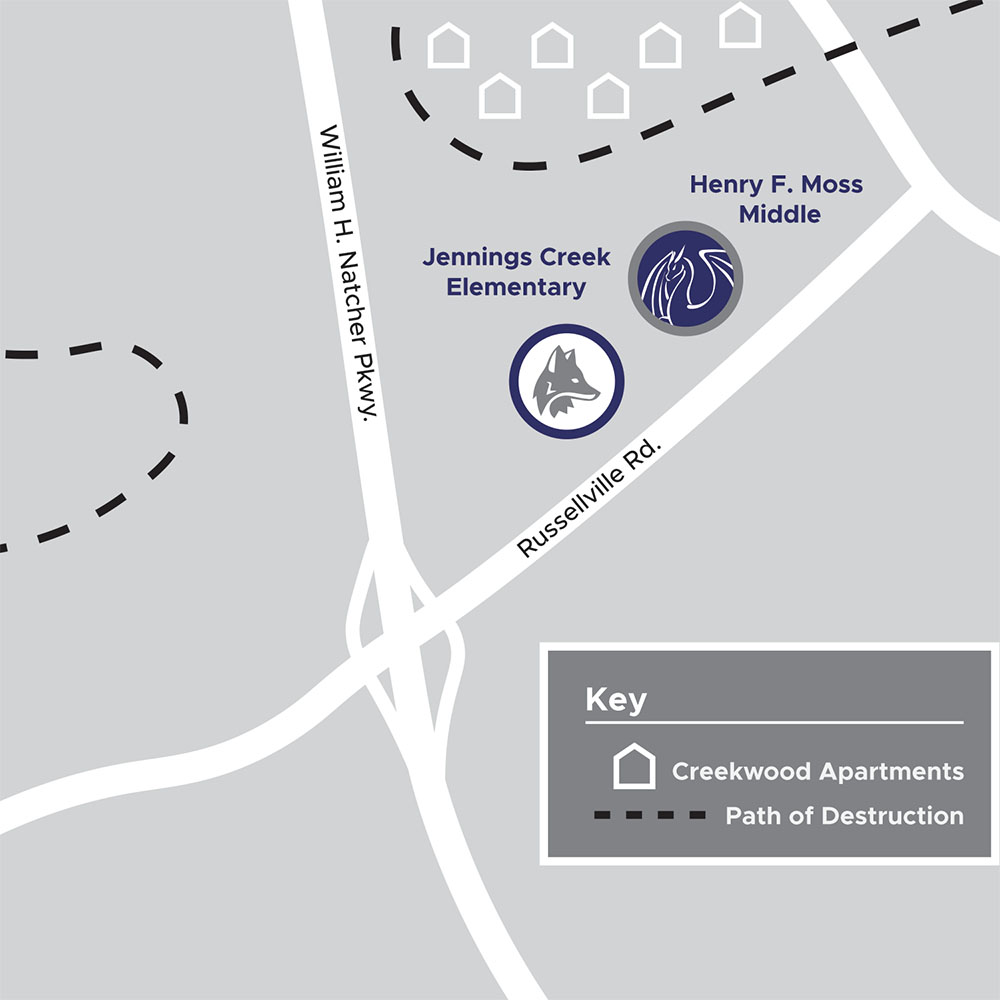

Rita Daniels, the principal of Henry F. Moss Middle School, said that her first priority after ensuring her family was safe was to check on her students. Along with her faculty and staff, she went searching in the affected Creekwood neighborhood behind the school the morning of Saturday, Dec. 11, 2021.

Daniels said Moss Middle School teachers also began calling households one-by-one to ensure each of their students were accounted for. She said the faculty members used charts to document whether students were safe, their locations and what their families had lost.

She said before classes resumed after the tornado, the Warren County School District brought mental health counselors to Moss Middle School. The counselors, who were present the first week after school resumed, then visited each class to inform students about the service.

Daniels said students will occasionally still speak to counselors even now, almost a year after the event but that the students are resilient.

“Young people are resilient in that they move past things a little bit faster than sometimes adults do,” she said.

Daniels said she’d never seen anything like the damage the tornado left in its wake on TV or in her life. She said she had thought about tornadoes in a general sense but that she truly understood their destruction after seeing their effects in Bowling Green.

“When it touches down in your neighborhood, you really understand and take in the ramifications of what a tornado can really do – the devastation it can cause,” she said.

Daniels said Warren County Public Schools set up an area within Cumberland Trace Elementary School to supply impacted families. She said the effort moved to Moss Middle School’s cafeteria because the location was more accessible.

“In our cafeteria, we suddenly had what I called ‘the store,’” she said. “We ended up being the hub by which supplies were provided for families, and so our cafeteria, our hallways had food. Whatever you named, we had it.”

Daniels said the school opened their doors from morning until evening. Families were able to get supplies such as clothes, tarps, flashlights and batteries.

“When you think about the devastation of a tornado, in the impact of that, people lost everything,” she said. “When I say ‘everything,’ that means a toothbrush; that means socks; that means deodorant. That means everything that anybody would need.”

She said Moss Middle School was blessed because of the donations they received from various organizations and people.

Daniels said the volunteers included churchgoers, Warren County School District employees and more.

When the December tornado hit, Daniels said she was only five months into her job as principal and that she was amazed by the effort of her community.

She said you sometimes don’t know who people are or what they’re made of until something like a tornado happens.

“That’s when you see what kind of community you have,” she said. “That lets you see what kind of employees you have.”

Daniels said nearly a year after the tornado, some families have not been able to stabilize themselves and are still without homes.

She said part of what made the tornado’s devastation hard was that Moss Middle School lost one of their students, Nyssa Brown, in the tragedy.

Brown, who was 13 years old, was one of seven people in her family to die in the tornado and was the last person in Bowling Green to be found during search efforts following the disaster.

Daniels, who had a close relationship with Brown, said the tornado impacted her on a personal level.

“I feel horrible when I see Nyssa’s grandparents because I know who they are, and I saw them right as they found out they lost their family,” she said. “I saw their anguish; I saw their pain. Even to this day, that family is still living in that same devastation.”

Daniels said she spoke with other students, families, faculty and staff about their experiences with the disaster.

She said one student at Warren Central High School told her she didn’t know how she was alive after the tornado picked her up and dropped her.

Daniels said one of her cafeteria workers remembers being asleep upstairs in her duplex, unaware that the tornado was occurring, and waking up face-first in mud. The woman suffered a few broken bones but still has her life.

Daniels said considering how the tornado “completely flattened and completely destroyed” the Creekwood neighborhood behind Moss Middle School, it was amazing that more lives weren’t lost in the damage.

“While I’m sad on one hand, I’m grateful and feeling blessed on another,” Daniels said.

Will Spalding, the assistant director of the English language and federal programs for Warren County Public Schools, said the Warren County School District had to figure out logistics concerning how to bus students to keep them in their same school for the rest of the school year.

Spalding said that his family was spared from the tornado’s damage but that it was difficult seeing its destruction.

“It looked like something that you would see in, you know, a country that’s war torn, and it’s weird to think that that’s our community,” he said.

Spalding said that because the tornado had torn open homes, people were staying in their houses without electricity to protect their belongings.

Along with other faculty and staff members, Spalding went out to affected neighborhoods and encouraged people who were sleeping in their cars to come to the shelter.

Spalding said some families couldn’t speak English, and refugee advocates arrived to work with international families and help interpret their conversations with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

He said former students from the GEO International High School, where he is the principal on records, and Warren Central High School would show up to Jennings Creek Elementary School and ask who they could translate for.

Spalding said seeing this effort was really cool, despite the devastation.

“What fills your bucket is to see everybody kind of coming together and say, like, ‘Hey, I’m talented in this,’ or ‘I have this skill, so I can help,’” he said.

Spalding said one thing Warren County School District employees learned was the importance of having strong relationships with students to be able to do a home visit or find them on a social media platform and send a message to check on them.

“It took a village, and it was incredible to see the amount of teamwork and just willingness (of) people to put in extra hours not just because they had to, because they wanted to,” Spalding said.

He said the outpouring of support immediately after the tornado was overwhelming but that a lot of families, including international households, didn’t have an extended support network.

He said some families ultimately left Warren County because of this lack of support. Additionally, he said some families are still struggling because they didn’t have insurance on things they lost to the tornado. He said these families continue to rely on donations and need support.

“As we come up on the year of this, there are still plenty of people out there who need help,” Spalding said.

While Spalding said he is worried about these people not knowing how to advocate for themselves, the Warren County community is trying to find unique ways to continue to support those affected.

Dee Anna Crump, the director of the English language and federal programs for Warren County Schools, said Jennings Creek Elementary became a “command center” for distributing donations after the Creekwood neighborhood behind Jennings Creek and Moss Middle sustained damage from the storm. Jennings Creek also eventually became the hub for the Red Cross to offer additional support for the neighborhood, she said.

“We literally took buses out into the community that night, trying to get people out of their homes to get them to Jennings Creek,” Crump said.

She said donations were taken at South Warren Middle School but eventually were transported to Moss Middle School because affected families, most of which were from the Creekwood area, lacked the transportation to get to the high school.

When the Red Cross and the Federal Emergency Management Agency arrived in Bowling Green to help with disaster assistance, Crump said they found the city’s international community to be different from others across the U.S.

“A lot of people don’t always realize that our international community is very different than what a lot of people are used to,” Crump said.

She said The Red Cross and FEMA are used to going to states like Florida or Texas where the second most commonly spoken language is Spanish.

Crump said there are over 100 languages spoken within the Warren County School District and that some families “are not literate in their language.” She said even if volunteers could translate or hand international families documents in their native languages, the effort was difficult.

“We were giving them languages that they had literally never heard of,” she said.

Crump said she thinks trust played a factor in the international families’ responses to help from the Red Cross and FEMA.

“I think with our families, they knew us, so they were very comfortable dealing with us, but it was a little harder maybe sometimes dealing with people from the outside,” she said.

She said transportation was one of the hardest barriers to overcome after the tornado because of a long process working through insurance companies.

Crump said in one international family, the wife died and the husband and son suffered extensive injuries in addition to losing their car.

Crump said the wife in this family handled everything, including paying the bills, and now, after her death, the family had lost all paperwork and was “starting from

ground zero.”

“Some of our international families are much more compartmentalized, even more so than maybe American families,” she said.

Crump said in the time after the tornado, a lot of services had to be implemented at the elementary school concerning mental health and trauma.

She said some students were now homeless and unable to get to school because they were displaced.

“We had a responsibility as a district to transport them back to the school that they were in when the tornado hit,” she said.

Crump said Jamie Woosley, the principal of Jennings Creek Elementary, began driving a bus to some of the different motels around town to pick students up for school.

All the while, faculty and staff members focused on helping families regroup in terms of acquiring housing and making deposits to help them get furniture, mattresses and more.

“You just don’t think about the fact that a lot of these families literally lost everything,” Crump said.

She said a significant number of faculty and staff were impacted in the storm and lost their homes, so Crump and others tried to find the balance of helping students and their families while also helping staff members and their loved ones.

“It’s been a continued effort,” she said.

Crump said the tornado reminded her of the “selflessness” of the Bowling Green community, and she was impacted by the resilience of Warren County School families.

“Personally, it was a good reminder of the good in the world and that we are a strong community,” Crump said. “I think it helps put in perspective what’s important.”

Woosley, the Jennings Creek Elementary School principal, said Bowling Green and the Warren County School System has one of the most diverse communities in Kentucky.

“When this devastation happened, it didn’t matter what language you spoke. It didn’t matter what religion you were; it didn’t matter what color you were,” he said. “Nothing mattered except just getting out and helping people.”

Woosley said it was interesting to see that even when he and others tried to help families who’d lost their homes, the families would decline and request that the supplies be given to someone else.

“Everybody was trying to look out for everybody else,” he said.

Like Crump, he said there was a trust issue when helping families, but that members of the Warren County community trusted the school system when faculty would knock on parents’ doors and their children would run to greet them.

He said he remembered going to a house where the parents told him they didn’t want to lie to their children and say everything would be OK after one of their classmates had passed away from the tornado. He said the family told him they didn’t know how to handle the situation.

Woosley said he told the parents to bring their children to school the next day because mental health counselors would be on-hand.

“There’s a right and wrong way to handle those situations, so that was a big learning curve for me that I wasn’t prepared for,” he said.

Woosley said the Warren County School District supported his faculty in their unique efforts to help those affected.

“We tried to eliminate the barriers to let people do what their natural instincts and natural abilities allowed them to do,” he said.

When a few teachers asked if they could start a childcare service, he said the district approved.

“The teachers in the community and the school district, you know, they were so instrumental in just helping people,” he said.

Woosley said he and other volunteers from the Warren County School District helped people regardless of their age or if they had a child at Jennings Creek Elementary.

“It was not just our school. It was not just our kids. It was the community,” he said. “If you needed help, we helped you.”