Story by Evynn Pollard and Cecilia Alali

Photos by Brodie Curtsinger

Design by Amelia Curry

Editor’s Note: This article was originally released in Issue 17 of the WKU Talisman print magazine. Click here to read more articles from the Talisman’s semesterly print.

“We had a lot of good times,” artist Alice Gatewood Waddell said while recalling visiting her family in Jonesville, a once prominent Black community. “Good family reunions, a lot of celebratory occasions. For our family, it was the gathering place, and it’s also the place I got acquainted with my elder relatives.”

Now, the land where that community existed is home to part of WKU’s campus.

According to the article, “Jonesville and the Legacy of Slavery at Western Kentucky University,” Jonesville dates back to when enslaved soldier Taylor Hobson returned to his former Warren County slave labor camp after passing through the heavily populated Black community Jeffersonville, Indiana, in 1865. Post-emancipation, Hobson was a free man who may have desired to reside in a similar Black space when he returned to Kentucky, the article states.

Fanny Wooldridge married Taylor Hobson the following year, and with six children, the article states, Hobson’s property along Russellville Pike would kickstart the beginning of Jonesville. The Kentucky Historical Society explains that it was officially established in 1881 and thrived for nearly a century self-sufficiently before it was demolished to expand WKU’s campus.

Marker 2052, sponsored by Jonesville descendant Maxine Ray and WKU, remains a lone fixture commemorating where once stood.

“It was bordered by Dogwood Dr., Russellville Road, and the railroad tracks. The community grew to include several hundred residents, an elementary school, businesses, and two churches,” the marker states.

Jonesville’s direct neighbor, Bowling Green, was a segregated city until 1955 and adhered to Jim Crow laws that set the legal groundwork for discrimination. According to the “What Happened to Jonesville” exhibit in the Kentucky Museum, which showcases the complicated timeline of the town, Jonesville became a safe space for Black families to build their lives.

Ray said the town’s main social center and community core was built around faith with the help of Mount Zion Baptist Church, which was demolished and forced to rebuild near 227 Carpenter Court in a state effort for relocation, according to the Louisville Courier-Journal. The church was there 90 to 100 years before Jonesville was officially established, Ray said.

“All of our extracurricular activities were done at the church,” Ray said. “You could even go down, and they would play baseball in an empty field next to the church. At Halloween time they would do a bonfire, and we roasted weenies and marshmallows on the fire, and then they would start telling ghost stories.”

Because Bowling Green businesses legally didn’t allow Black individuals in their doors, Ray said Jonesville residents created their own companies to be self-sufficient.

The “What Happened to Jonesville?” exhibit lists some of the shops that thrived in Jonesville. Hardin’s Roadhouse (well known in the community for BBQ sandwiches), Taylor Sanitation, Henry Callaway’s Fruit Stand, Blewett’s Filling Station, Audrey Bailey’s Beauty Shop, Stallard’s Chicken Butcher Shop, Mae Wade’s Restaurant, Loving’s Barber Shop and Pryor’s Cleaners were all Black-owned and run. Some of the businesses, the exhibit continued, were run right in the owners’ homes.

“Our parents were really good about making sure we had everything we needed in our community,” Ray said. “It was safe to us. You could go to anybody’s house; you didn’t keep your doors locked; in the summertime, we slept with the windows up to let in the breeze.”

Waddell is a fourth-generation Jonesville descendant. She is also a WKU alumna and executive director of the Bowling Green Human Rights Commission. Waddell said her memories of Jonesville were idyllic.

“The land itself had a lot of things that you could live off of,” Waddell said. “People farmed. People had crops, gardens, lots of trees that bear fruit — plums, peaches, apples, walnuts — you name it.”

However, Waddell said there were rumors that the neighborhood was “blighted” and that Jonesville was quickly generalized as such.

According to the “What Happened to Jonesville” exhibit, during the 1950s, there was a large increase in student population post-World War II at WKU. The Department of Defense attributes this nationwide boom to the GI Bill, incentivizing the expansion of college campuses to accommodate veterans returning to school.

In 1957, the Board of Regents started to discuss expanding the campus, however, there was land privately owned by Jonesville residents obstructing their expansion.

According to WKU’s website, only five properties “interfered” with expansion plans, and after they declined to sell, condemnation proceedings continued – adding multiple others.

Ray said the community banded around the church in a town-wide attempt to push back on former President Kelly Thompson’s plan to demolish Jonesville.

“Our pastor wrote a lot of letters, but it just seems like when it was time to go meet with the city commissioners, all the city commissioners knew what the plans were before he even got there,” Ray said.

In 1963, Jonesville was acquired under the Urban Renewal Program. The program set aside $780,685 for the acquisition and project development of the area and was approved federally, according to the Park City Daily News. After that, WKU expanded the campus by removing the Jonesville community.

“At first, they were trying to say we were squatters squatting on land that wasn’t ours, but we did have deeds to the property,” Ray said. “The people that lived in Jonesville had fairly decent jobs for the time. They made a good enough living to pay for that property.”

After Jonesville residents refused to sell their property to WKU, condemnation proceedings were initiated, according to WKU’s website. The website said that Jonesville homes were deemed “blighted,” or unsafe to reside in, for issues as small as lacking off-street parking.

Ray said the community’s protests were futile.

“We stopped telling them where things were, ‘cause every time we said where something was they’d tear it down,” Ray said.

Waddell said she watched as Jonesville slowly was demolished over time, starting with where Diddle Arena stands today.

“I suspected the demolition was coming because the neighborhood was all taken gradually,” Waddell said. “My great-grandparents’ house was still there. When the Diddle Arena was built, we just naturally assumed everyone is going eventually.”

Many Jonesville residents were forced to leave their homes for a fraction of their properties’ value, according to WKU’s website, and some were paid as little as $100. Relocation efforts landed Jonesville residents in “flood-prone” and unclean locations, according to the Louisville Courier-Journal.

Other athletic facilities such as Houchens-Smith Stadium and the Nick Denes Field now occupy the land formerly owned by Jonesville residents.

Peggy Crowe, the director of the Counseling Center and Student Accessibility Resource Center at WKU, said she often reflects on the fact that an entire community once stood where WKU’s athletic buildings are.

“Sometimes I look out, and I pause and think – there were thriving families that lived and worshiped and cut hair and did laundry and tilled land and built homes right where you and I are sitting,” Crowe said.

Crowe is the current chair of the Jonesville Reconciliation Workgroup, created in April 2022 by President Timothy Caboni. Crowe said that this workgroup gathers WKU and Bowling Green community members with descendants of Jonesville families. Together, they create actionable steps to educate about and support the perseverance of Jonesville.

“Our goal has been educating faculty, staff, students, the community at large, and then incorporating descendants into these conversations because it’s never been done before,” Crowe said.

Ryan Dearbone, a Jonesville reconciliation Workgroup member and assistant professor in the broadcasting department, said the group’s mission centers on bridging gaps between historic Jonesville and present-day WKU and Bowling Green communities.

Dearbone said the group meets monthly to formulate ideas on how to reach and educate the local community. Then, the group meets with President Timothy Caboni to present the ideas, and Caboni enacts them. He said it’s a collaborative effort because Caboni often approaches the workgroup with his ideas as well.

However, Dearbone said the group’s initiatives depend on the feedback from Jonesville descendants who are part of the group.

“They have an insight that we believe is a big game changer,” Dearbone said. “It makes our job easier because we have a direct pipeline to someone intimately involved in Jonesville — that knows what it was and could be remembered as.”

Crowe said the group has hosted multiple reunions and symposiums to speak with descendants about their hopes for preserving the legacy of Jonesville.

“Our main purpose is to appropriately address the dismantling of this beautiful community, right here where we learn, teach, compete, research, live,” Crowe said.

Saundra Ardrey, the previous chair of the workgroup and a retired political science and African-American studies professor and department head, said the workgroup communicated with descendants directly to guide their actions.

“We reached out to the residents and descendants of Jonesville to ask what they wanted, because, for a long time, the Black community has been upset with Western for taking that land and not really acknowledging what their role was,” Ardrey said.

Ardrey said the workgroup is also discussing creating a physical marker on campus separate from Marker 2050 to honor and memorialize the community. She said the workgroup is also implementing scholarships for Jonesville descendants and hopes to have Spirit Masters highlight the history of Jonesville on tours so visitors know what land they stand on.

“Dr. Caboni tasked us with finding out how best to remember and also pay a little respect to the Jonesville community because Western destroyed that vibrant Black community to expand for the athletic sports complex,” Ardrey said. “So, Dr. Caboni wanted to say it’s time to recognize Western’s part in that and see if we can’t make some type of (reparation).”

Another contribution the Jonesville Reconciliation Workgroup has made to preserving the Jonesville legacy is through the “What Happened to Jonesville?” traveling pop-up exhibit from the Kentucky Museum.

“We usually have the traveling exhibit at the Kentucky Museum to educate students and the community about what Jonesville is. Show them that we’re standing on land where people’s living rooms and kitchens were or where churches and barber shops stood,” Crowe said.

Brent Bjorkman is the director of the Kentucky Museum and the Kentucky Folklife Program as well as a Jonesville Reconciliation Workgroup member. Through the Kentucky Folklife and Community Scholars programs, a group of community members were able to conduct interviews and meet with descendants of Jonesville to gather the resources and information used in the traveling exhibit.

“I brought up to Dr. Caboni that creating the exhibit would be a great way to contextualize the history so people can not only hear but really see what we’re talking about,” Bjorkman said.

Bjorkman said he encourages visitors to experience the exhibit and that he was proud of the knowledge he can pass down from his research on Jonesville.

“Something I’m fond of telling people that come in is whether your family’s been here for two years or 200 years, we’re all Kentuckians, and our voices all need to be heard.”

Dearbone said he was shocked to learn the history of Jonesville.

“It wasn’t until I got involved with this project that I actually learned the history of Jonesville and how much WKU is intertwined with it,” Dearbone said. “Without Jonesville, there’d be no WKU – at least on that part of the Hill.”

Dearbone said he remembers hearing descendants talking about seeing Mount Zion Baptist Church getting burned down in the process of building WKU’s athletic buildings. It was powerful, he said.

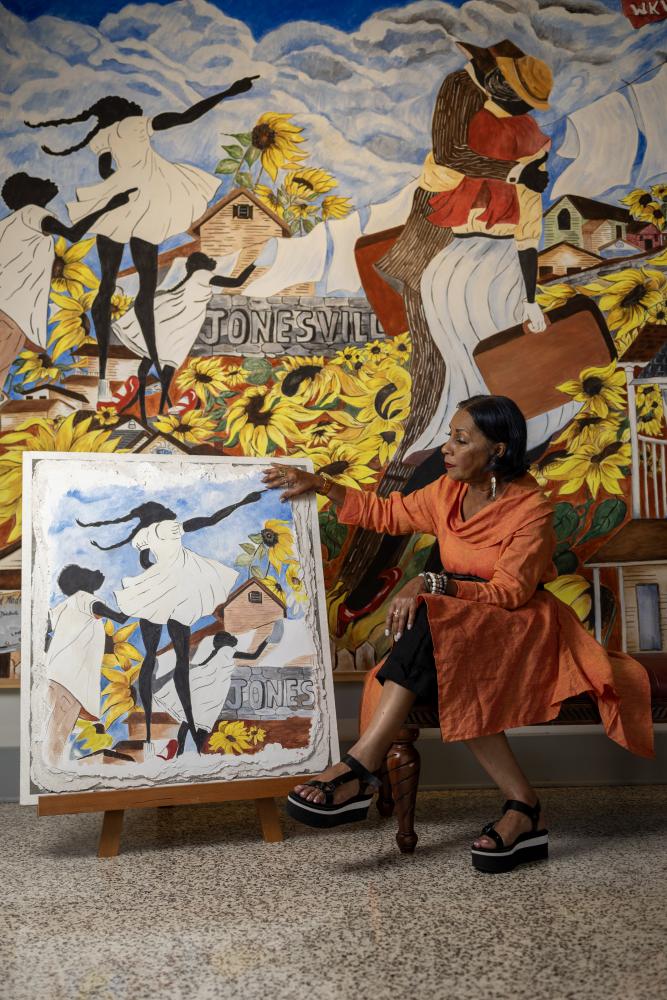

Now, Dearbone said the group has had regular events, including two meetings over the summer with descendants, the creation of the traveling exhibit, and the unveiling of the Jonesville Fresco Buon Mural created by Waddell.

“This is a good example of how over time things can be healed,” Dearbone said. “It’s a sign of growth for the university.”

Dearbone said the Jonesville Reconciliation Workgroup has multiple events in the works, including a documentary with WKYU PBS that he said will bring the story of Jonesville to a national audience.

“This documentary is a big success because now there can be worldwide knowledge of the story of Jonesville,” Dearbone said. “This has turned from something confined to Bowling Green to, now, widespread knowledge of this community and what it meant to this area.”

Ultimately, Dearbone said he is proud to be part of the committee making a long-lasting impact that remains “part of the university’s fabric.”

Crowe said that the Jonesville Reconciliation Workgroup and “What Happened to Jonesville?” traveling exhibit are just two examples of acknowledging otherwise forgotten history.

“Our American past is complicated and messy and horrific, but we should talk about it and acknowledge it and then figure out how we can be better moving forward,” Crowe said.

Though Jonesville may physically be gone, Dearbone said the workgroup’s current and future initiatives will offer a way to preserve the town in the minds of each person in Bowling Green and on WKU’s campus.

“We don’t want Jonesville to be just one sentence in a history book about WKU’s legacy,” Crowe said. “Jonesville is too beautiful of a story.”