Editor’s Note: This article was originally released in the WKU Talisman print magazine on Wednesday, April 24, 2024. Click here to read more articles from the Talisman’s semesterly print magazine.

Madison Weis was in Cyprus during her semester at sea when she realized the severe bloating she felt in her stomach during her periods and the numbness in her legs were abnormal compared to other girls’ menstrual cycles within the program.

“I just thought that that’s what happens when your period was coming, but none of my friends could relate, which was, like, the first red flag,” she said.

Nearly two years later, Madison Weis, a senior from Oswego, Illinois, said she is still searching for a concrete diagnosis of her chronic condition, though she suspects she has endometriosis.

Missy Travelsted, an assistant professor in the graduate nursing program at WKU, said via email endometriosis is a condition where tissues similar to the lining of the uterus occur outside the uterus.

During a menstrual cycle, the uterine lining thickens and is then shed during a period. In endometriosis, the uterine-like tissues outside the uterus also thicken and bleed but are not shed from the body, causing inflammation, scarring and painful cysts.

Madison Weis, who suspects she has endometriosis, listens as her friend and fellow sorority sister, Kayla Dakin, gives her updates on Monday, Feb. 12 about fraternity events across campus. (Photo by Von Smith)

Endometriosis can result in a buildup of fibrous tissues between pelvic organs causing them to “stick” together,” Travelsted said.

“I often visualize endometriosis as kudzu. It grows everywhere and takes over,” she said.

The Mayo Clinic lists painful periods, pain with sex, painful bowel movements or urination, excessive bloating, nausea and more as symptoms of the menstrual disorder. Travelsted added that heavy periods or bleeding between periods are another symptom. Additionally, she said endometriosis may increase the risk of ovarian cancer or endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma, another cancer.

Endometriosis, which affects 1 in 10 women, is not usually visible on imaging tests and must be diagnosed through surgery, creating a barrier for women, according to a study conducted by Yale Medicine. On average, American women will suffer from the condition for 10 years before receiving a proper diagnosis.

“Endometriosis often goes undetected for years because the abdominal pain associated with the condition is mistaken for menstrual cramps, or because there may be no symptoms,” according to Yale Medicine.

According to VeryWell Health, the average yearly cost associated with endometriosis — including testing, misdiagnoses and surgery — in the United States is $12,118 per patient. However, as patients delay their diagnosis, the costs increase with the average indirect yearly cost of the chronic disorder due to untreated symptoms being $15,737 per patient.

Researchers are seeking less invasive ways to diagnose the disorder and determine its severity, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Travelsted said that while there is no specific lab test to confirm endometriosis, the gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with biopsy, where laparoscopy can also be used for treatment by the removal of endometrial tissue. She added that ultrasounds can reveal cysts associated with endometriosis, or endometriomas, that are most commonly found in the ovaries while an MRI can visualize the location and size of endometriosis growths and be used to plan surgery.

Madison Weis takes 290 milligrams of Linzess in her bedroom on Saturday, Feb. 24. Weis takes Linzess every day to treat irritable bowl syndrome with constipation. (Photo by Von Smith)

According to the National Institutes of Health, during a laparoscopy a surgeon makes an incision to view the reproductive organs, intestines and other surfaces to determine if any endometriosis is present and what stage they may be.

Laparoscopic surgeries usually have a shorter recovery time with smaller scars compared to traditional open surgeries, or laparotomies, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. Additionally, intense heat can be used to destroy the tissues.

“Many women can get relief from endometriosis symptoms and pain with treatment,” according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. “However, endometrial tissue may grow back, and symptoms may return even after surgery.”

Hormonal therapy methods, which include contraceptives like pills, patches, shots and vaginal rings, are possible treatments for endometriosis, according to Travelsted. Additionally, different formats of the progestin hormone, including the Depo-Provera shot and the Mirena IUD, can be administered to stop menstrual periods and the growth of endometriosis tissue.

Travelsted said medications like ibuprofen or naproxen sodium, which are nonsteroid anti-inflammatories, can also be taken to diminish endometrial symptoms.

She said diet and other alternative treatments like acupuncture, chiropractic care, herbs and supplements may treat and potentially prevent endometriosis. She said avoiding foods including those high in fat, red meat, gluten and soy can reduce inflammation. Vitamin D deficiency is another contributor to endometriosis, so taking Vitamin D supplements, fish oil, Vitamin C, turmeric and Vitamin E have all been found to improve symptoms.

A hysterectomy with the removal of the ovaries is often considered the most effective treatment of endometriosis, Travelsted said, but it is the last resort.

Madison Weis said she first began to believe she had endometriosis after experiencing numbness in her legs from her lower back to her pelvic area to just above her knees. She said she could still walk but would experience “sharp, shooting pains” for around 30 seconds to a minute in addition to being unable to breathe.

She said this symptom would continue the week leading up to her period and the week of, with the first week being worse than the second. After a year, her symptoms worsened, and she said her stomach would become inflamed and bloated.

“It would look like I’m five months pregnant,” she said, referring to endo belly, or the cyclic bloating of the abdomen, according to an article on endometriosis written by researchers Renata Voltolini Velho, Franziska Werner and Sylvia Mechsner and published by the National Library of Medicine. “It would be so painful because, like, no matter how much I would (try), I couldn’t suck in; like, it was just stuck at that spot. I would get super hard as a rock. You could punch it. It’s like a bulletproof vest.”

According to the National Library of Medicine, endo belly occurs during the second half of the menstrual cycle leading up to menstruation, and the abdomen becomes increasingly bloated, causing discomfort and pain due to elevated sensitivity within the intestinal wall.

When Madison Weis experiences endo belly, laying down helps.

“With my stomach, it’s like I’m so bloated to the max, and it’s so painful that I’ll be on all fours,” she said. “Being on all fours or, like, falling to the ground is literally like the only thing that will help, and then the stomach thing will last like an hour. There’s no telling when it will go away.”

Madison Weis said she wondered if she had a gluten allergy or lactose intolerance causing her bloatedness, but her symptoms come on randomly with cramps so painful she is sometimes woken up in the middle of the night, unable to breathe.

Madison Weis picks up her sorority sisters and friends in her Hyundai on Wednesday, Feb. 24. Weis, her sorority sisters and friends meet at Spencer’s Coffee where they “catch up on tea” from the previous week. (Photo by Von Smith)

She said she once couldn’t produce a bowel movement for up to two weeks due to issues with her stomach, citing constipation, which is another symptom of endometriosis, according to the Endometriosis Foundation of America. She said she “loses her abs” when she wakes up in the middle of the night and has to try lifting herself up using her arms.

“Nothing really ever makes it better or go away,” she said about her cramps. “When I get them, I’m, like, bawling my eyes out. It happened in class one time, and I couldn’t even focus on what the teacher was saying. There’s like tears coming down my eyes in class.”

Madison Weis compared the feeling within her body to a state of fullness.

“It feels like I’m so full, like I ate a whole chocolate cake, even if I’m not full, and then when my legs get super tingly, it’s like there’s rubber bands around my hips all the way to my knees,” she said. ”It feels like it’s just cutting off the circulation.”

After researching, Madison Weis said she suspects she may have sciatic endometriosis, which the Seckin Endometriosis Center defines as a condition where tissue resembling the lining of the uterus grows around the sciatic nerve, which extends down each leg, putting pressure on the nerve and causing pelvic, hip and leg pain. According to the National Library of Medicine, sciatic nerve endometriosis is often misdiagnosed or diagnosed late, which can aggravate the emotional and physical distress of affected patients.

Madison Weis said her illness causes her to occasionally cancel plans with friends due to pain, and it impacts her education.

“There’s a couple times where I couldn’t get out of bed to be able to go to class, and it’s embarrassing because you don’t know when it’s gonna come,” she said. “If I’m giving a presentation, and all of a sudden, I just can’t feel my legs, and it’s like 30 seconds to a minute where I can’t speak.”

Madison Weis said if she is actively doing something when she suddenly can’t feel her legs and is unable to speak, people can visibly see that something is wrong with her based on her facial expressions but can’t decipher what’s occurring due to the lack of outward visibility of her pain.

While there have been instances where Madison Weis feels she’s “gotten lucky” by being alone when her pain begins, she realized on a family trip that something had to change. She spent time sobbing about the pain she was in and unable to breathe or talk after she and her family flew to Hawaii. When her parents asked what was wrong, she complained of internal pain in her stomach and legs.

Madison Weis participates in Alpha Omicron Pi’s sorority chapter meeting in the basement of the sorority house on Monday, Feb. 12. On top of maintaining two jobs, Weis is active in her sorority and volunteers for various charity events. (Photo by Von Smith)

“I would say that’s when my parents were like, OK, this is really serious,’ when they saw me literally crying over it,” she said. “When I was little and I’d go to the doctor, and they’d be like, ‘Rate your pain on a scale of one to 10,’ I’d always be like, ‘Uh, four.’ I’m not gonna say 10; that’s dramatic. This is like 11.”

Madison Weis said while both of her parents are supportive of her medical journey, she’s grateful for her mom, who is persistent in determining what’s wrong with her daughter, despite Madison Weis accepting her condition as her life and something she has to deal with.

“She’s gone out of her way to make sure that all these appointments happen,” Madison Weis said. “She even keeps a notes list. If I tell her something that’s happening, she adds it to the notes, so when I go to the doctor, I say everything I’m experiencing, but then she is also there to reiterate things that I’ve said in the past that I’m forgetting.”

Madison Weis said she rants to her mom via text each time she experiences symptoms, which she said has been especially comforting when her friends didn’t understand what she was going through.

“Thank God my mom believed me every single second of the way,” Madison Weis said. “My mom doesn’t know what’s wrong either, but she still believes me.”

Madison Weis said she sometimes feels doctors don’t take her complaints seriously.

“Me and my mama have brought up the term “endometriosis” to them sometimes, and they’re just so quick to be like, ‘Oh, well, I don’t know about that,’” she said. “They just dismiss it so much. Even if it is endometriosis, they’re so quick to not diagnose it because there’s no cure for it. So I guess maybe because they know there’s no cure, they’re just like, ‘No, that can’t be it.’”

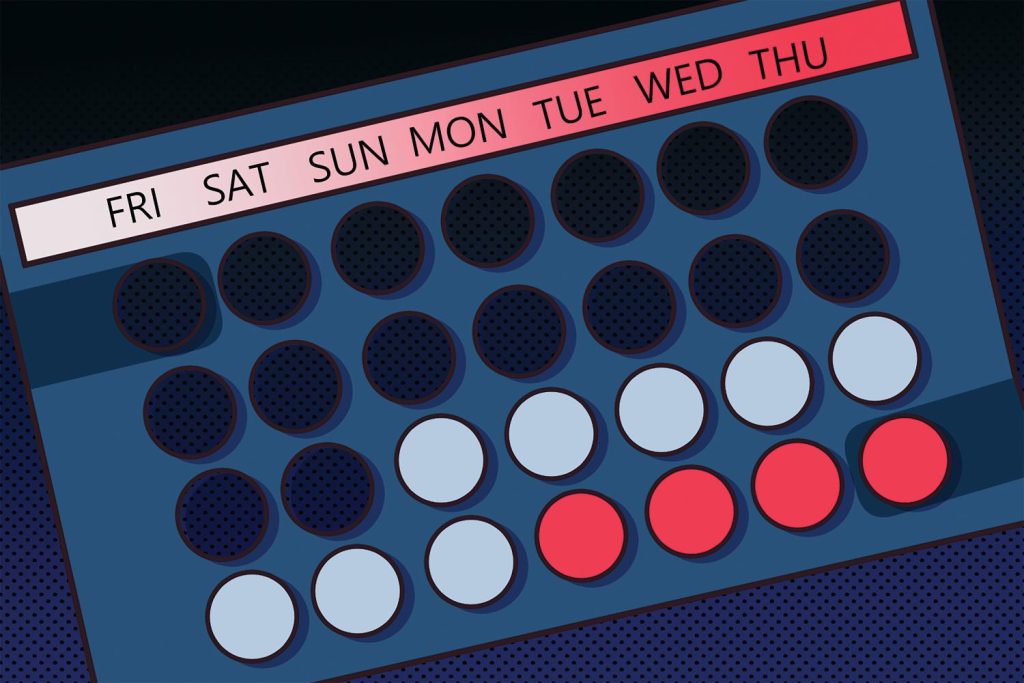

Diagnosing endometriosis requires an invasive surgery examining the uterus. The menstrual disorder affects up to 10% of women between the ages of 15 and 44, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. (Illustration by Faith Connolly)

Her mom, Megan Weis, said the lack of concrete diagnosis for her daughter is “concerning.” When Megan Weis had an MRI on her back, she said doctors discovered fibroids in her uterus, so she wonders why doctors aren’t doing “more serious” testing on her daughter to diagnose her symptoms. Morgan Weis said she wondered why doctors didn’t immediately give Madison Weis an MRI versus solely performing an ultrasound, and whether there are better testing methods to produce a quicker answer.

“It just seems like we just keep getting pushed from one doctor to the next; it’s like no one’s giving us answers,” Megan Weis said. “Like, really, we’ve got to take medicine for the rest of our life to not have this bloat in our stomach? Like, that doesn’t seem right, so I just feel like we’re chasing down answers. Do the doctors not have any answers? Are they trained to push you from one doctor to the next? It just doesn’t seem like it should be this hard.”

Megan Weis said it hurts to see her daughter in pain.

“As a mom, you just want to take that away from them, and I don’t want to experience it either, but, like, you want to take that pain away from your daughter. You’re just trying to help her cope until it passes,” she said. “When I’m not at school with her, it’s like, I can’t do anything but listen to her. I’m like, ‘Drink water; take ibuprofen.’ Are those even the right answers?”

Madison Weis said in dismissing the possibility of an endometriosis diagnosis, some of her doctors have speculated her diet may be to blame for her bloating, with one specialist attempting to place her on the FODMAP diet, which is designed to help people with irritable bowel syndrome or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“At one point, I had an Excel sheet of everything I would eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, alcohol, daily drinks like coffee, and the things that would trigger my stomach to get super big and my legs to hurt,” she said.

Madison Weis said the things she consumed never correlated with her symptoms.

“It just didn’t make sense. (My mom and I) tried telling them that, and obviously they don’t understand that because they’re like, OK, well, that makes no sense, so I don’t know,’” she said. “I just feel like no one ever knows, and they just keep tossing me around.”

Madison Weis said it makes her unhappy to know that endometriosis is a chronic, incurable disease.

Hormonal birth control, including contraceptives like pills, are possible treatments for endometriosis, according to Missy Travelsted, an assistant professor in the graduate nursing program at WKU. Medications like ibuprofen or naproxen sodium, which are nonsteroid anti-inflammatories, can also be taken to diminish endometrial symptoms. (Illustration by Faith Connolly)

“This is such a prominent thing in women, and it’s very common; it’s just that not a lot of people get diagnosed,” she said. “It’s such a common thing that there should be more emphasis on the treatment for this, especially even the diagnosis, like, there has to be another way than surgery — that’s a little extreme. It’s a shame that there’s not a treatment for it, especially when so many people are going through it.”

Between 30 to 50 percent of women with endometriosis may experience infertility, according to research conducted by Massachusetts General Hospital. Women without endometriosis have an approximate 10% to 20% chance of getting pregnant each month while women with surgically documented endometriosis have a 1% to 10% chance, the study continued.

For Madison Weis, the chances of infertility are “devastating,” though she said she doesn’t want to speak it into existence.

“I want a family; that is my main goal in life,” she said. “That’s just something that’s always in the back of my mind. I can’t forget about that because I’m like, ‘Oh my God,’ like, if I couldn’t have a kid, I would be so devastated, so hopefully that’s not my case. I have every single symptom and, like, bad, so it’s a possibility that I think about.”

Megan Weis said her greatest hope for her daughter is that her symptoms will go away, and she will be able to live a normal life without pain.

Despite the uncertainty, Madison Weis said she doesn’t believe she’s experienced medical bias, though she did say she felt her male practitioner was more understanding than her female one.

“I don’t know if that has to do with the fact that maybe he doesn’t understand, so he’s believing everything I say, because if a female doctor has never gone through this, they’re going to be like, ‘Oh, well, it’s not that bad because I have periods too,’” she said.

She said her male doctor, who is her gynecologist, sought to create a step-by-step plan to decipher her illness and avoid surgery if possible while women doctors, like her primary care physician, would suggest one answer and say they were unsure of what to tell her regarding her experiences.

She added that, much to her frustration, one of her doctors recommended she start birth control to combat her symptoms, despite her already having a copper IUD. Madison Weis said she prefers holistic methods.

“I just don’t think birth control is the answer to everything,” she said.

Madison Weis said her IUD is non-hormonal, despite making her periods “10 times worse.” However, she said she was willing to endure the pain in order to not take birth control.

Close friends Kayla Dakin (from left), Tea Bleidt and Morgan McWilliams catch up with Madison Weis away from the action of their sorority’s “AOII-Hop” charity event in the Alpha Omicron Pi house on Monday, Feb. 12. (Photo by Von Smith)

“I got off birth control because it just made me a completely different person,” she said. “I had so much anxiety; I didn’t even know what anxiety was until I got on birth control. I couldn’t talk, like, normally. I was always, like, ‘What are people thinking about me?’ and now that I’m off of it, I feel so much better.”

Madison Weis said when she was prescribed birth control, she picked up her prescription at the pharmacy despite not taking it. She said her mother would mention how doctors suggested she take birth control at each of her appointments, but her doctors would disagree on an appropriate treatment.

“What people are prescribing me doesn’t make sense to another doctor, so it’s, like, OK, well, why am I even taking it?” Madison Weis said. “I just like holistic methods more, and so, like, if you’re gonna tell me to drink some tea, I’ll drink the tea; if you’re gonna tell me to, like, drink this magnesium, I would rather do that than be put on a pill every day,” she said.

Madison Weis said women with endometriosis should not give up even when doctors tell them to see a different specialist because they will eventually find the answer.

“You shouldn’t have to go through something like this because periods shouldn’t be painful,” she said.