Stuffing, gravy, potatoes, corn and turkey are piled on American dining room tables every year on the fourth Thursday of November. We say that we are grateful for the meal, for experiences, for one another. We give our thanks.

Would we feel differently if we lived different lives? If we had drawn another card, would our gratefulness for this feast be more genuine?

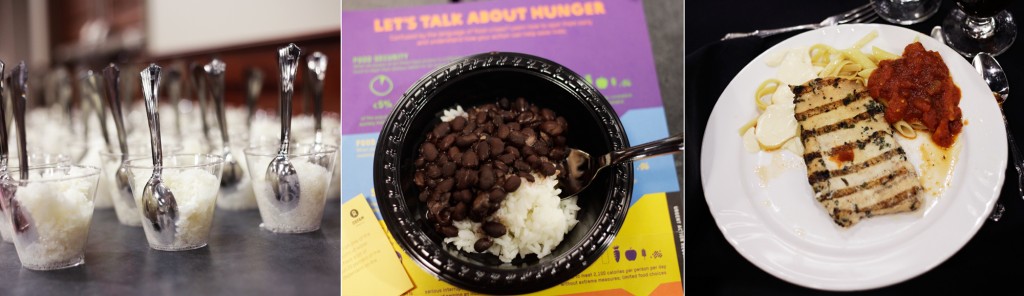

This year at WKU, Housing and Residence Life sought to raise thankfulness — along with compassion and awareness — by hosting a Hunger Banquet on the third floor of DSU. At this interactive event, the place you sat and the meal you ate were determined by your class, denoted by a randomly selected card marked upper, middle, or lower class and filled with a personality profile. The division of classes mirrored the injustice served to the 925 million people in the world without enough food to eat.

As the banquet began, the moderator first addressed the participants sitting at round, tablecloth-covered tables covered with salad, bread, chicken, cheesecake and two types of pasta. She said they represented the top 20 percent of wealth in the world, and she asked the audience to estimate the salary required to be a part of this exclusive and envied division. It only took an annual salary of $6,000 to be of elite status.

New Orleans freshman Ajah Marshall, who was fortunate enough to draw an upper class card, said she felt guilty seeing her friend and others in the lower class, sitting in the floor while she enjoyed cheesecake and an abundance of bread.

“I learned that people should be more grateful and feel privileged for what they have,” Marshall said.

The middle class sat at long, cloth-less tables, representing the 30 percent of the world population that receive $1,000 to $6,000 annually. They had less security and luxury than the upper class, but at least they could meet their daily needs.

The personality profiles on their cards revealed lives of small business owners in developing countries, where a simple problem could become an emergency. The group was served water with a bowl of rice and beans. Most said they felt full, but the meal was flavorless in comparison to the visible feast for the upper class.

On the floor between the two tables sat the lower class, where each member was served only one small cup of rice. They represented the 50 percent of the world that struggles to live on less than $1,000 per year. These people are frequently hungry and aren’t likely to own land or have access to clean water. Though the middle class could fall to the lower class with a draw of a card, the lower class was unlikely to ever advance.

Sitting wither her cup of rice, Meredith Kilgore, a senior from Bowling Green, said the banquet presented a new perspective on hunger.

“I’ve always been middle class,” she said. “With opportunities and without. In this environment, there are no barriers, you just see people. I think that’s one thing our society should see — that millionaires are no better than people that can’t afford dinner.”