Suellyn Lathrop, WKU’s archivist and records officer, sits at one of the tables stacked with memorabilia. In front of her is a neat pile of manilla folders and signs that have been sent in at the request of the archives.

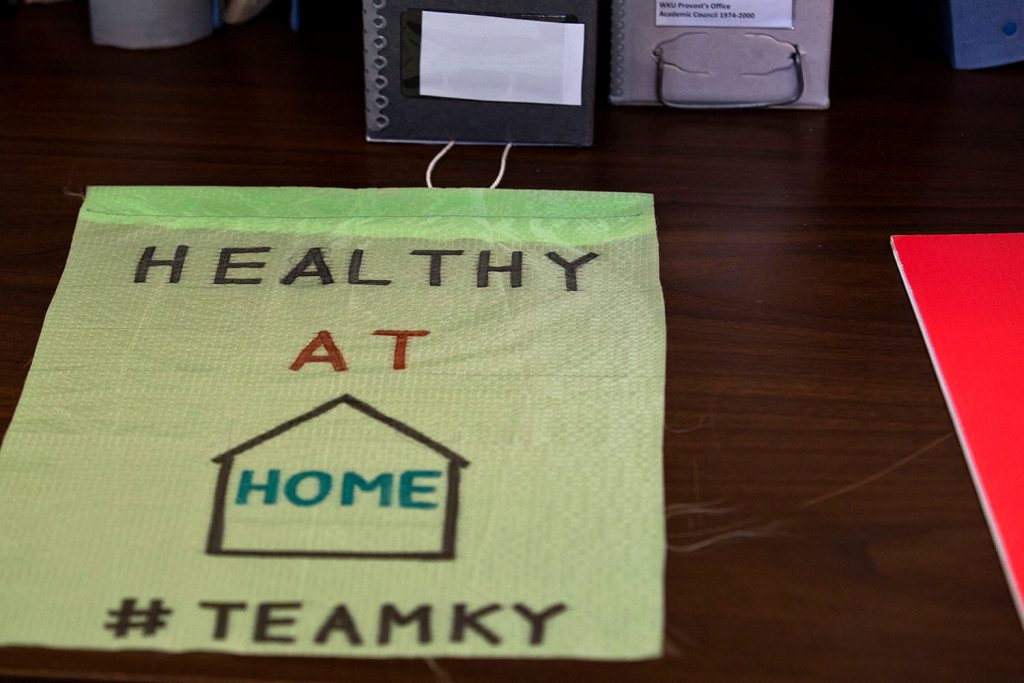

One sign congratulates alumni in WKU red. The other sign, a homemade tribute to the Healthy at Home order and those who have died during the pandemic, a reminder that the community has been greatly affected. “Healthy at Home, #TeamKY” is marked on the front of the sign.

Lathrop sifts through materials that get sent into the archives, including photographs, publications, audio histories and videos. She decides what to keep permanently in the archives and what they can part with.

“Photos are fun because you just never know,” Lathrop said. “Digitizing is interesting because things change … and then some things stay the same.”

Lathrop feels that it is especially important to document the university’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic since there was so little documentation on the response to the 1918 flu epidemic.

The university historian, David Lee, worked with Lathrop trying to find how WKU responded in 1918.

They went through local papers and Hardin Cherry’s personal correspondence. Cherry’s personal papers yielded the most results, though those were largely inconclusive.

Lathrop and Lee found a letter Cherry had written to his daughter. According to the letter, no students died on campus from the Spanish flu. About two-thirds of the student body had fallen ill, but no deaths were reported.

The archives have a limited record of any student response. There are no accounts of how student organizations responded, how classes changed or if any preventative measures were put into place.

“It closed down society in similar ways, but the Spanish flu had not fallen into the national narrative,” Lee said. “We want a fuller record, and we want a better understanding of what (the Spanish flu) was like internally.”

Lee and Lathrop both expressed a desire for the student body to become more involved in the archives, both to participate in documenting the pandemic experience but also to provide a window into student life during COVID-19.

While the archives hold an abundance of records, much of the material comes from the president’s office, Lee said.

“The archives have a hole: It’s student experience,” he said.

The archives are easily accessible to the university at large. In the digital age, the COVID-19 archives consist mostly of online records, personal accounts from faculty and students, digitized signs and transcripts of speeches. Signs range from garden signs to congratulatory signs for WKU alumni to signs posted in the hallways advising social distancing and mandating masks.

Among the items in the COVID-19 archives, a haiku submission by English professor Tom Hunley caught Lathrop’s eye. Hunley has written and submitted a total of six poems to the COVID-19 archives.

“They’re about coping with the confusion and despair of the moment,” Hunley said. “I like the poems better than anything I could say about them.”

Hunley’s poems are among 138 submissions to the COVID-19 archives.

Anthropology courses have made contributions to the archives, along with some miscellaneous submissions from professors and medical students in hope that less mystery will exist with WKU’s response to this pandemic compared to 1918.

This pandemic is unprecedented, and as such the archives are taking whatever material they can. Submissions to the COVID archives are open-ended, Lathrop said.

The topSCHOLAR database is a resource where students can access the archives and scholarly research for free. Lathrop encourages students to use the databases to the fullest extent, including submitting to the archives.

“If anybody wants to contribute, because who knows when this will end. It’s open-ended at this point,” Lathrop said.

People can submit archives electronically to [email protected] or in paper to 1906 College Heights Blvd. #11092.