Within the gray walls of the Warren County Regional Jail’s small library, Jennifer Douglas waits patiently for class to begin. She has just gotten off from a shift in the jail’s kitchen, where she works seven hours a day and five days a week preparing meals. Around the table sits a small group of women who are part of the jail’s Relapse and Recovery Prevention class, a program meant to rehabilitate those with drug-related sentences. For the next hour, the women take turns speaking, analyzing past behaviors and looking toward the future. Jennifer is quiet, listening when others share. Her half-filled workbook contains curled handwriting and drawings of her family: her parents, two daughters, one son and eight grandchildren.

“I can’t be a mother from behind these walls,” Jennifer said.

Jennifer has been incarcerated for almost a year with charges in drug trafficking and bail jumping. This is not the first time she has been in jail, but it is the longest. According to the Vera Institute of Justice, the majority of women who are incarcerated are charged with lower-level, drug-related offenses, and 80% of incarcerated women are mothers.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)“We watch our mama,” Jennifer said. “Everything starts at home with our mama.”

For years, Jennifer said she watched her mother endure an abusive relationship.

“I didn’t want a man to push me over,” she said. “I was scared of becoming like my mom in that way.”

Instead, Jennifer tried to live independently as a single mother. She began struggling with drug addiction as an adult but remained the primary guardian of her three children.

“I’ve always told them to be better than me,” she said.

On a Friday morning, Ashley Douglas woke up in her apartment to use her breast pump while her 3-month-old daughter slept in the room above. Ashley is Jennifer’ youngest daughter, a stay-at-home mom with two children. She described herself as the caretaker and protector of her family. While she pumped, her older sister Alessandra Douglas, who lives nearby and visits often, burst through the door begging Ashley to fix her hair and make her lunch. Ashley complied. Soon, the home filled with laughter and jokes between sisters. They argued who has the best chicken recipe, neither budging in their own self-assuredness. Alessandra’s one-year-old son, Ace, bounded through the house like a small tornado, energetically reaching for toys, picture frames and his mother’s hair. Ashley reminded them of her sleeping daughter, and the room quieted but was never silent.

Ashley and Alessandra agreed their family has always been close knit.

“We’ve always had an open relationship, me and my brother and my mom,” Ashley said. “If there’s something going on, we talk about it.”

As Jennifer struggled with addiction and spent time in jail, that closeness was tested. When Jennifer was incarcerated last year, Ashley, Alessandra and their brother were frustrated and discouraged. Ashley decided to maintain their relationship despite frustrations and offered her a place to stay after her sentence was complete.

“Even though I don’t understand her decisions sometimes, I still try to be there for her,” Ashley said. “If you lose everyone when you go to jail, you give up. I do everything that I can to be there for her.”

Doug Miles, program services director at the Warren County Regional Jail, said many of the inmates, especially those who struggle with drug addiction, lose ties with their families during their incarceration. This makes the process of reentry, or the transition from jail to the outside, even more challenging.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)“In the cycle of addiction, people burn bridges,” Miles said. “When they’re released, they don’t have anything to go back to except what got them in trouble in the first place.”

Jennifer said the support of Ashley and her other children has encouraged her to continue working on herself and thinking toward the future.

“They are standing behind me,” Jennifer said. “No matter if I fail, they still love me. In their eyes I’m no failure. I know I can always come back up.”

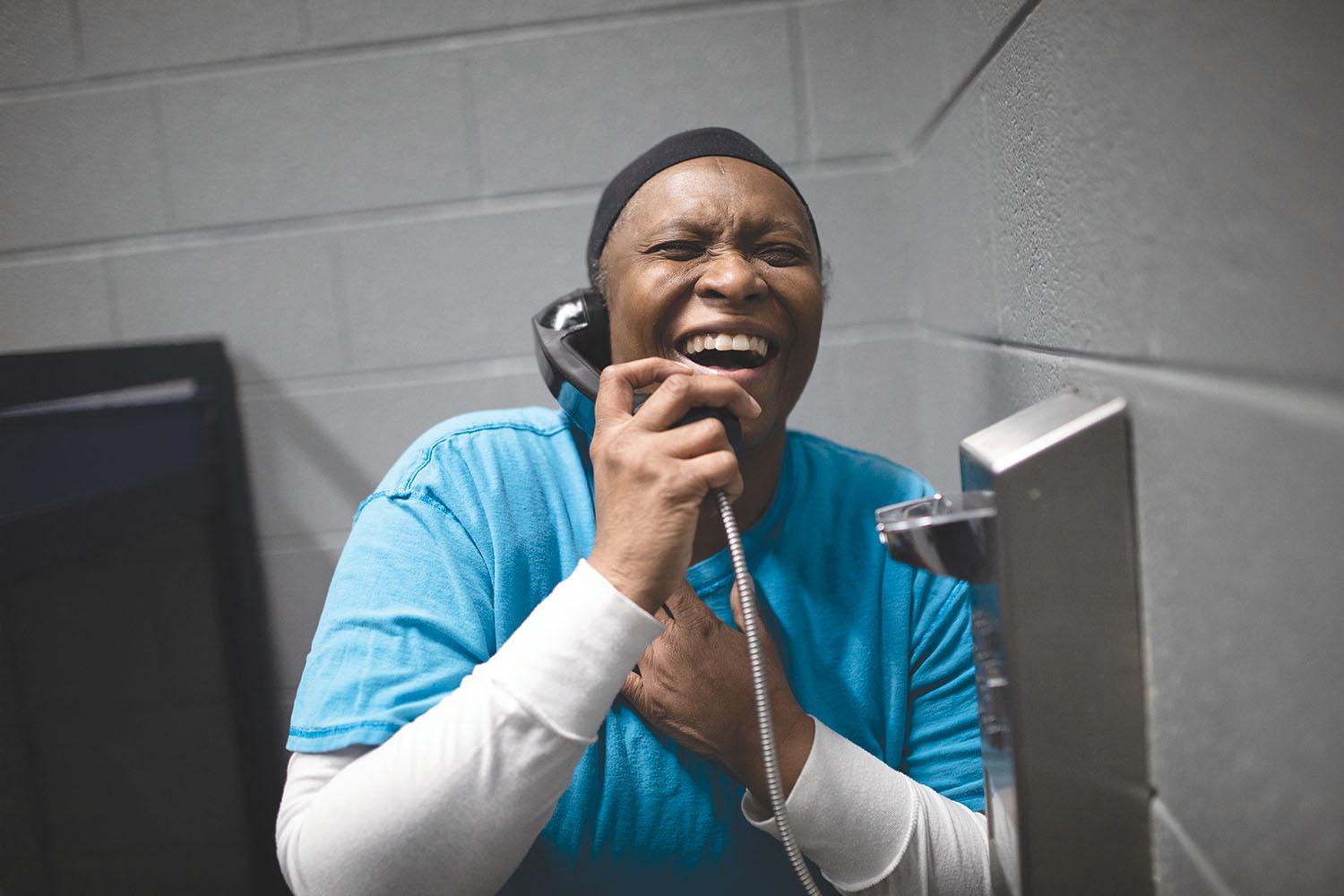

Right now, Jennifer and Ashley maintain their relationship through phone calls.

In prisons and jails across the U.S., these calls come at a price. In the Warren County Jail, inmates who wish to use the phone must purchase phone cards. For $10, an inmate can make three calls for up to 15 minutes apiece. In the state of Kentucky, where inmates can be paid as little as 9 cents an hour for their labor, phone calls can be very costly.

Jennifer and Ashley talk whenever she can afford it, which is about once a week.

“The best I can do is to be a voice,” Jennifer said. “To say ‘I love you, I’ve got you, just hold on — I’ll be there soon.’ I don’t want that anymore. I want to call and say, ‘I’m on my way.’”

Jennifer and Ashley agree this type of a relationship has its limitations. Since Jennifer was incarcerated last year, she has missed birthdays, holidays and daily life with her family. During Jennifer’s incarceration, Ashley became pregnant with her first daughter. Jennifer said the pregnancy and the birth of her granddaughter were the hardest things to miss.

“She was limited in what she could do, but she did everything that she could,” Ashley said.

When Ashley had doctor’s appointments, Jennifer asked a family friend to accompany her as a mother figure. Other times, Jennifer called with encouragement and support.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)Still, Ashley was left to navigate her pregnancy on her own for the most part. When she wanted to learn how to breastfeed, she consulted YouTube. She went to appointments with her mom’s friend or sometimes on her own. Ashley said she felt her mother’s absence the most during her labor, which lasted 30 hours. She spoke to her mother about it afterward.

“When she asked me how it was, I told her I needed my mama.” Ashley said.

Three months after the birth of her daughter, Ashley is still anticipating her mother’s release.

“As a mom, I would say I’m superwoman,” Ashley said. “It’s a round-the-clock job, and sometimes I’m exhausted. I need her here.”

After her release, Jennifer plans to start a job close to their home and take care of her grandchildren as much as possible. She said she is most looking forward to taking her grandsons fishing and holding her granddaughter for the first time.

Regardless of where Jennifer is — in the jail, in Ashley’s home or anywhere else — Ashley said she looks to her for guidance as she navigates motherhood.

“I love my kids unconditionally, which is a reflection of how I was brought up,” she said. “She showed me what it means to give your all.”