It is pitch black until the light from flashlights and headlamps make their appearance and cave dwelling critters scatter. The air is cool and damp, and it is silent other than the periodic drip of water that slips through cracks in the limestone ceiling and softly lands on the slimy cave floor. This is new territory, but it all connects to something greater, like pieces of a stone puzzle that lie just below the surface.

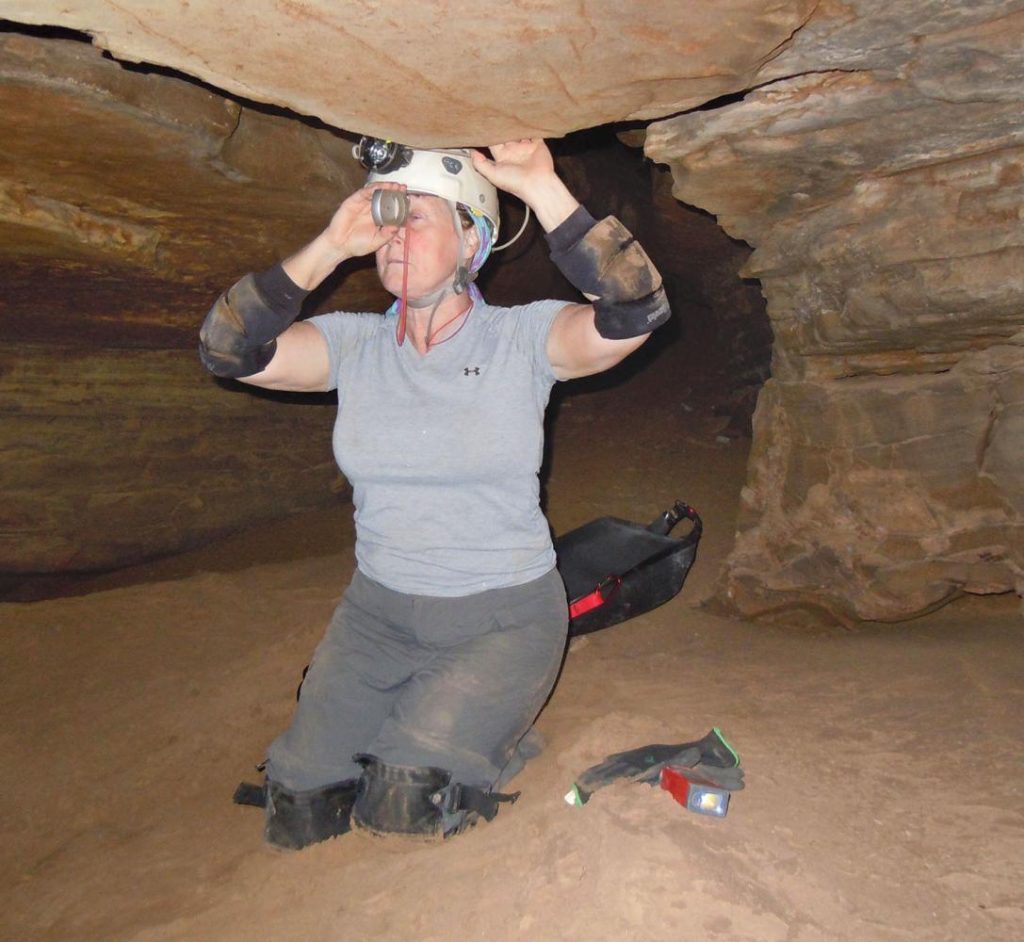

Former WKU English professor Elizabeth Winkler has spent a lot of her life exploring caves like this. She, along with a team called the Cave Research Foundation, now regularly spelunks in Mammoth Cave in order to better understand the over 400-mile-long cave system.

“It’s kind of become a lifelong obsession,” Winkler said. “What started out as tiny little things, kind of exploded into an entire life.”

She said she began her hobby while teaching English in Mexico in the early 90s. The cave, Tia Rosa as she recalls, was horizontal and had to be entered through a river.

“We had to swim through it,” Winkler said. “I had regular flashlights taped to a construction helmet. The Mexicans I was caving with seemed to take this all as normal. I fell in love with the adventure right then.”

After her initial caving experiences Winkler decided to apply to graduate schools in the U.S. that not only had a linguistics program, her area of study, but that were also near caves, ready to be explored.

“I applied to four programs that had Creole’s, which is the field of linguistics I’m into, and caves nearby and got into Indiana University and started caving,” Winkler said.

On her very first trip to Mammoth Cave during graduate school, a fellow spelunker asked if she would be interested in mapping caves. After agreeing to go on the mapping trip in Mammoth, Winkler was able to understand the excitement.

“I immediately got addicted to exploring and mapping the cave,” Winkler said. “I got addicted to the puzzle.”

Jackie Wheet, a Mammoth Cave tour guide and park ranger from Alvaton and fellow member of the Cave Research Foundation, holds this same sentiment.

“Every expedition, the more we find, we’re kind of putting another piece in the puzzle, and it’s starting to make more sense to us, like here’s where the cave goes, here’s why it goes this way,” Wheet said. “But also, you’re getting to go somewhere no one has ever been and that’s pretty cool.”

During the expeditions, cave explorers often find new passageways and rooms that no one has been in before, or that have been untouched for centuries, Winkler said.

Christopher Groves, a WKU professor of earth, environmental, and atmospheric sciences and fellow Cave Research Foundation member agrees with Winkler’s sentiment, “When you’re in an unexplored passage, you’re literally the first person in the whole history of the world to walk in that passage, and that’s pretty neat as it is,” he said. “That experience of being in unexplored passages, for some people, it’s like a drug. It’s addictive. It’s such an incredible rush.”

The Cave Research Foundation is a non-profit that has been granted access to the cave system in Mammoth. From this relationship, the foundation has virtually exclusive rights to map Mammoth Cave, and they have been doing so since 1958. The group recently found new parts of the cave, making Mammoth the longest cave system in the world. Some of the original crew of 1958 still cave with the group to this day, Winkler said.

“One of the things I know about caving from looking at people who are 20 years older than me, who I’m going into the cave with, is I can be doing that in 20 years,” Winkler said.

Spelunking is not just a hobby. For some people like Winkler, Wheet and Groves, caving has been a lifelong passion and holds personal significance in their lives.

Groves recalled being six years old and being enticed with the curiosity incited by caves. He said he had seen a picture in National Geographic of two men standing in a nondescript cave with mud up to their waists.

Groves said he was initially shocked due to the potential of unknown creatures, but his fear soon shifted into curiosity. To be any more remote and removed from the rest of the planet than that, you’d have to be up in a spaceship somewhere and I thought ‘Well man that’s for me.’”

Wheet also compared exploring the dark, untouched caves to space exploration.

“I’ll never be an astronaut and get to walk on the moon, but I can go into a cave and say I was the first one to step here,” Wheet said.

Both Winkler and Groves agree that the seclusion of the caves has also provoked feelings not necessarily of religious nature but something that is close to the spiritual.

“There’s a presence about being in a cave,” Winkler said. “There’s just a feeling of ‘I’m out in the middle of nowhere in a tiny little place, and I’ve crawled down three hours of holes and whatever, and I’ve gotten in here, and now I’m in this giant room.’ You go from the small to the large. It just seems very — I’m not sure spiritual is the word — but very, very moving to be there.”

For over 200 years, Mammoth Cave has been the subject of various scientific studies and explorations, and a large tourist destination for South Central Kentucky. According to the National Park Service website, the cave was first explored by Native Americans in the area between 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. To this day, new sections of the cave are still being mapped by geologists.

Groves stated that he sometimes gets a feeling of strange familiarity when exploring.

“It’s like déjà vu, not exactly the same experience, but very much of something being kind of familiar beyond the normal,” Groves said. “Just some sort of connection that I don’t know how to describe, but definitely very real, and I felt it several times in the Mammoth Cave area.”

Time spent in caves brings one closer to a sense of spirituality as well as fellow spelunkers. Winkler met her husband while caving with the CRF, and since then they have flown across the world to explore and map different caves.

“We met underground and were friends for years before we got married,” Winkler said. “You figure anybody who can love you exhausted, dirty, muddy, tired, cranky, after crawling through a river of mud, will probably love you when you’re cleaned up.”

Together, they have mapped caves in 20 different countries within the span of 20 years.

Winkler, Groves and Wheet said they will continue spelunking as long as their bodies can handle it.

“If my knees don’t give out on me, I would love if I could still do this 20 years from now; it’d be awesome,” Wheet said. “There’s a saying, you get bit by the cave bug and catch cave fever, and that is true, very true.”