At just under 60 degrees, Saturday was an unseasonably warm November day in Memphis, Tennessee. The bright Memphis sun beat down on the Lorraine Motel, home of the National Civil Rights Museum and site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, as nearly fifty WKU students filed out of a red charter bus.

The students who came to visit the museum for a field trip were enrolled in two different classes: philosophy of public space and American studies.

The air in and around the museum was restless. This was the weekend after Donald Trump was elected the 45th president of the United States in a victory that NPR called a “major upset” and the “capstone of a tumultuous and divisive campaign.”

As in 1968, the museum was a hub for those searching for unity, justice and wisdom in the legacy of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

Bowling Green senior Magnolia Gramling noted a spike in attendance at the museum from her own last visit.

“I was moved by how many people were there this time,” Gramling said. “I remember it being very empty the last time I was there, and I think that [spike in attendance] has everything to do with this new focus on the presence of hate in our country, the trouble people are having with it and this need to reflect on the ways people have dealt with this hate and backlash in the past.”

King came to Memphis in 1968 in response to the Memphis Sanitation Worker’s Strike, a protest against poor working conditions, low wages and the recent gruesome deaths of two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker.

He had spent the last year criticizing President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty for not going far enough and calling for a “radical redistribution of economic and political power.” This trip was no different.

“If something isn’t done, and done in a hurry, to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is doomed,” King said in his last speech.

Now, the surrounding blocks of the Lorraine Motel are home to barbecue joints, coffee shops, art galleries and even an American Apparel store. The only telltale sign of the area as it was pre-gentrification is the presence of barbed wire fences and crumbling sidewalks several blocks northeast.

And, of course, there’s Jacqueline Smith.

The gentrification of Mulberry Street

Weather-worn books, educational flyers and photocopied newspaper articles littered a tarp-covered table at the corner of Butler and Mulberry streets. A sign affixed to a nearby telephone pole read that Jacqueline Smith had been protesting there for 28 years and 293 days.

A Memphis native, Smith lived in the Lorraine Motel from 1973 to 1988, when she was evicted for the museum’s construction. At the time, the surrounding neighborhood was home to primarily low-income, black families, said WKU political science professor Roger Murphy. Smith was the Lorraine Motel’s last tenant.

“Been a long time, but I still feel the same way,” she said. “All these people around here are thieving.”

Smith had plenty of recommendations for reading materials about gentrification and King’s message, including his own book, “Strength to Love.” She encouraged the small but curious crowd to take flyers home, and she told them that the Lorraine “ought to be used for some good” as a home of education and assistance for the poor, rather than a money-making tourist attraction.

A young, female police officer drove past, and Smith interrupted herself to wave hello.

“Hello, Officer!” she said. “We appreciate you!”

She turned to address the surrounding bystanders.

“They ain’t hurtin’ nobody,” she said. “I’ve been arrested many times … you have to respect the law enforcement. Ain’t no sense being out there acting foolish.”

This is Our America

Recent protests against president-elect Trump have been making headlines in the week since the election — including on WKU’s campus in which a protest outside Pearce-Ford Tower on Wednesday, Nov. 9 resulted in the arrest of five students.

Across the street from the museum, a crowd of people of all ages and races was gathered at Founders Park. Many of them were college students from the University of Memphis. Some wore rainbow gay pride flags draped on their backs. Others held signs bearing phrases like “Love will triumph.”

One-by-one, protesters stepped up to speak through a megaphone. One woman introduced herself as a child of Mexican immigrants. She said she’d never held a megaphone and told the crowd not to be afraid to speak out.

Another woman, a freshman at University of Memphis with purple dreadlocks, introduced herself as, “Tamara, a proud millennial.”

“I refuse to be quiet …” she said to enthusiastic applause and drumbeats. “This is our America.”

Protestors across the street joined arm-in-arm and began singing the Beatles’ song “Let It Be” as WKU students entered the museum through an extensive security check.

Keeping the Dream Alive

Owensboro senior Curtis Edge said visiting the museum was a unique experience because it “let you walk through history.”

The museum was organized chronologically, beginning with an exhibit on slavery which featured life-size mannequins of slaves bound by chains and packed into three foot tall slave quarters on the middle passage.

Audio of creaking wood, sloshing water, and human wailing completed the unsettling display, causing one museum-goer to turn away, saying, “I can’t even look.”

Edge echoed these sentiments, saying many of the museum’s artifacts surprised him.

“They had an iron collar with bells on it that the slaves wore so that the masters would know where they were,” Edge said. “It was eery.”

The next exhibit focused on Jim Crow, the name for the formal set of laws that legalized segregation. It featured a set of Ku Klux Klan robes from the 1950’s hanging from the ceiling, ominously lit by a spotlight.

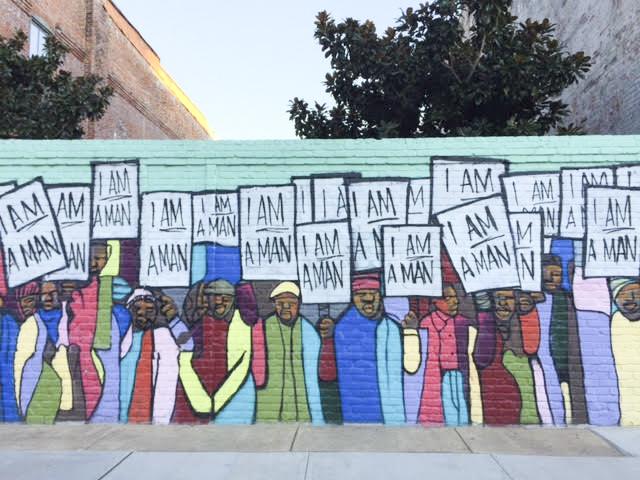

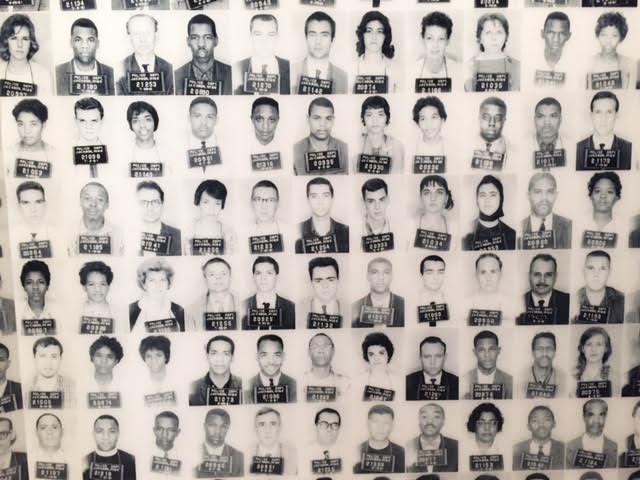

The next featured a reproduction of the Montgomery, Alabama city bus where Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat, followed by a wall of mugshots of protesters arrested during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the subsequent Freedom Rides.

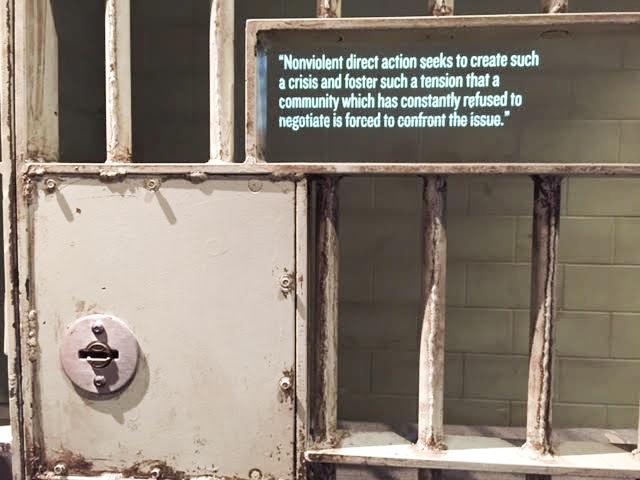

The next was a pastel blue display made to look like a ’60s diner, featuring more mannequins of black youth at a sit-in protest. A film tutorial on non-violent protests was projected on the tiled wall behind them.

The exhibit’s theme was how civil rights groups organized and carried out non-violent demonstrations.The next was about how they were beaten and jailed anyway.

Gramling said that to her, the museum emphasized the necessity for community organization and political action.

“I think [that] flies under the radar because a lot of the most visible points of the movement were the products of such intense organization and community-building experiences that started on the local level,” Gramling said. “That’s the thing that I took away from it the most and the thing I want to continue to preach to people who will listen.”

I’ve been to the mountaintop

The museum ended at rooms 306 and 307 of the motel — the rooms where King spent his last hours, preserved behind glass as they were in 1968 by the motel’s owner, Walter Bailey.

Signs called for “silence and respect” as lines of visitors filed past the rooms, stopping to gaze out the glass barrier to the balcony where King Jr. was standing when he was fatally shot by James Earl Ray. The square of concrete where he stood has been replaced, but a red and white wreath marks the approximate spot where he stood.

Just across the street, golden sunlight illuminated the last of the protestors collecting their belongings as the demonstrations wrapped up for the night. To the left of the museum, Smith stood on the corner of Mulberry Street as she has for nearly three decades.

Gramling reflected on what the visit to the museum meant to her in the wake of the recent election and political unrest.

“It was definitely a comfort I will say,” Gramling said. “Although, it’s the site of, some would say, the death of the Civil Rights Movement because of the profound leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, there’s something comforting about knowing that you stand on the shoulders of really amazing and brave people.”