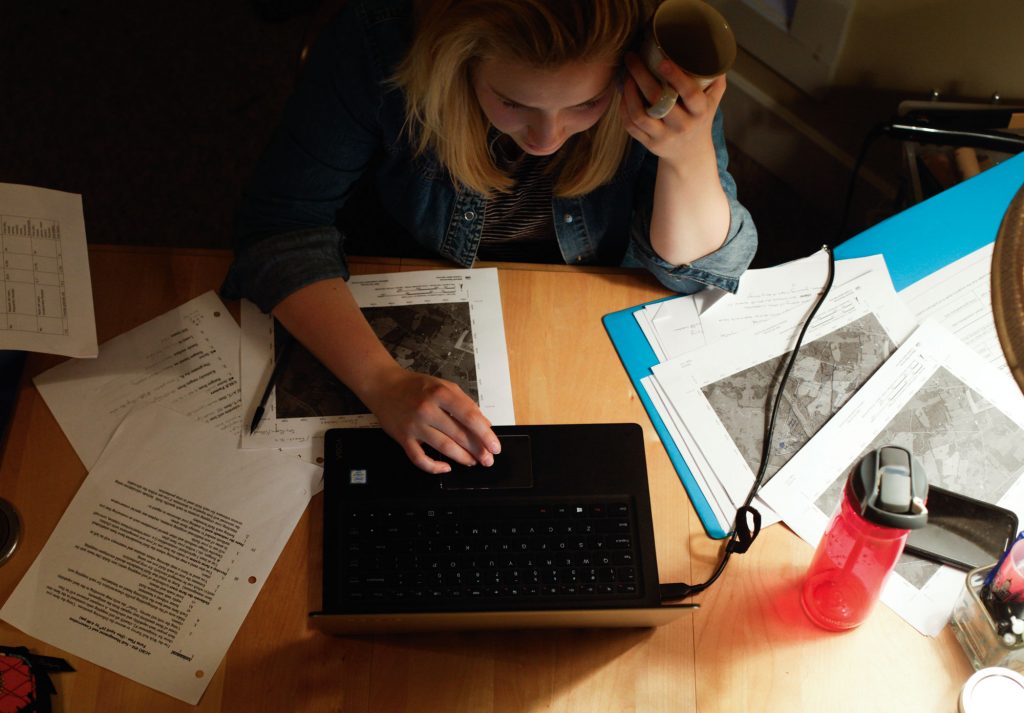

It began in seventh grade with a life science class. Then it was eighth grade physics and chemistry. That year they built mousetrap cars, and she loved the way things came together when she sat down to build them. By the time Megan Laffoon finished her first biology class as a junior in high school, she had already discovered her passion for science.

“I would go home and read my textbook and just be in love with it, and that’s when I knew that this is what I should do,” Laffoon said. “If you enjoy reading the textbook, that’s probably a good indication.”

Laffoon, a Louisville senior, was a biology major, an Honors College member and a Chinese Flagship Program student. She was the president of the ecology club and the recipient of two prestigious and nationally-competitive awards — the Goldwater and Boren scholarships.

“I love that science is all about connecting people to things that matter — whether that’s to something like environmental degradation or where their food comes from,” Laffoon said.

One detail about Laffoon made her stand out from many of her peers and future colleagues — she was a woman in the world of science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM.

STEM had become increasingly popular in both the academic and professional world. Ogden College of Science and Engineering, which housed the STEM disciplines, saw enrollment climb more than 10 percent from 2010-2016.

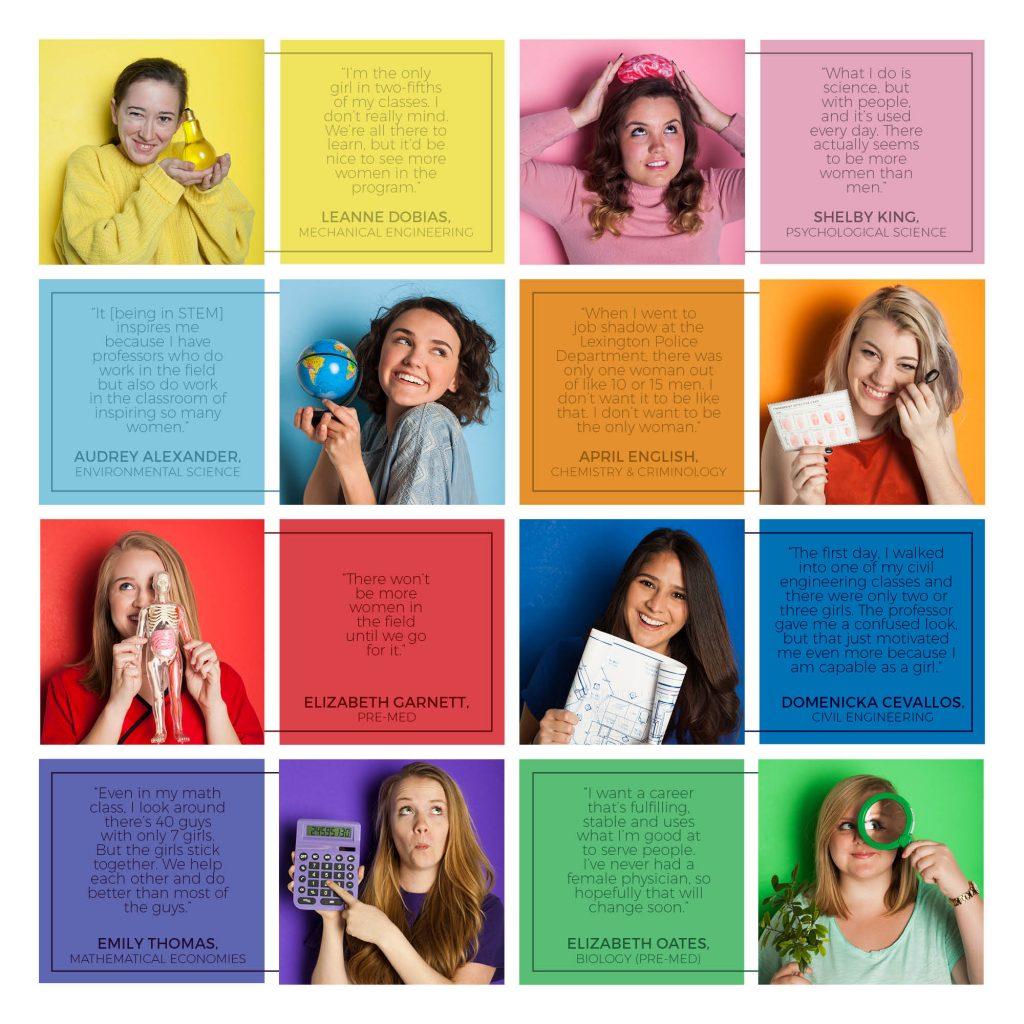

Despite the growing interest, STEM remained predominately male. Women held only 25 percent of all STEM jobs in 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. WKU’s numbers were slightly higher. Although female students made up 57 percent of the undergraduate class, they only accounted for 36 percent of the STEM-related disciplines in fall 2014, according to the 2015 WKU Factbook.

Ogden’s dean, Cheryl Stevens, was the face of the STEM program. Stevens said the issue of gender disparity in the STEM field wasn’t just at the undergraduate level. She attributed it to what she termed as the “leaky pipeline.”

The “leaky pipeline,” she said, was the tendency for women to drop out of their career field after going through school.

“For a variety of reasons, women start out and get their undergraduate degree — they might even go to graduate school — and then at some point they say, ‘Well, this isn’t really for me. Maybe I’ll go into science education policy instead of being a line scientist,’” Stevens said.

Laffoon agreed that the gender disparity in STEM wasn’t due to just university-level issues. She thought the problem was the stereotypes girls learned at young ages.

At the Christian Academy of Louisville where she went to high school, Laffoon said she didn’t feel weird for liking science. But she did feel uncomfortable in math, a subject she said other people assumed she would do poorly in because she was a woman.

“It was always kind of a joke, but when you joke about something like that so many times, even if you know it’s not true, you start to believe it,” Laffoon said.

She thought hiring more female professors in Ogden could help women feel more comfortable there. Women only represented about 30 to 33 percent of the STEM faculty, according to Stevens.

Audrey Alexander, a freshman from New Deal, Tennessee, said women in STEM needed a “sticking together mentality” to support and encourage each other. She felt that building a community was necessary to combat discouragement and discrimination.

“Even just saying ‘I agree’ when another girl in my science class speaks out can bring a huge sense of validation,” Alexander, an environmental studies major, said.

She credited her academic adviser, Leslie North, as a positive influence on her college and career experience.

“I’ve had a number of professors, my adviser in particular, that have really encouraged me to find my passions and hold on to them,” Alexander said. “It is inspiring to see [female] professors doing work in the field, and also encouraging women.”

Women weren’t the only ones concerned about this issue on campus. Professor Chris Groves, one of Laffoon’s honors thesis mentors, was one of the two men on the Women in Science and Engineering Advisory Board. WISE, a program developed by Stevens to encourage female achievement in STEM fields at WKU, hosted events like lectures, book clubs and panel discussions.

Groves said that discrimination wasn’t always obvious. It could be as subtle as the standard use of male pronouns in scientific research.

“Everyone deserves the same dignity,” Groves said. “Otherwise, if we don’t talk about it, it’s easier to gloss over the discrimination without understanding and being aware of the solution.”

Laffoon’s future in science was bright. After finishing up her senior year and passing her honors thesis on karst rocky desertification and sustainable agriculture with distinction, Laffoon would continue her Chinese language study in China for a year before returning to the U.S. to continue her studies in conservation ecology.

“I’m proud of implementing and completing my own research project,” Laffoon said. “I’m proud that I did that and that I saw it through and it developed and I’m not ashamed to share it with people.”