This story was originally published in late November in “Power,” the third issue of Talisman magazine.

When Owensboro sophomore Noah Hancock was four years old, an audiologist informed his mother that he had no hearing in his left ear.

After receiving a cochlear implant a year later, Hancock recovered 80 percent of his hearing and began to learn sign language. Now, Hancock uses his hands and facial expressions to communicate — not letting his limited hearing affect his way of living.

Raised by his mother and grandmother, neither of whom know sign language, Hancock learned valuable lessons in communication and patience. Those lessons consisted of perseverance, lip reading and vocal pronunciation. Grade school was also a battle for Hancock. Learning alongside others who didn’t know how to successfully communicate with him made it difficult to make friends and socialize.

After doing copious amounts of research in high school, Hancock found a deaf university in Washington, D.C., called Gallaudet University. However, Hancock left Gallaudet University after one semester due to the intimidation of attending a predominantly deaf school.

“They all spoke in sign, so when I came back home I had to make the adjustment into normal speaking conversations,” Hancock said.

His relationship with his mother was such an important part of his life, and Hancock felt that being that far away from home and not knowing anyone made the decision to come back to Kentucky an easy one.

Transferring to WKU immediately felt right when he got involved with the American Sign Language community on campus. Hancock didn’t let his lack of hearing hold him back from gaining a higher education and having a normal college experience.

Utilizing both his eyes and his hands to communicate, Hancock has learned to adapt and is always up for a conversation or the opportunity to meet someone new. Hancock holds the community outreach position in the American Sign Language Organization (ASLO) on campus, where he strives to be a vital role in its success. He is currently majoring in history and minoring in ASL.

“I wouldn’t mind working at a museum or even as a reenactor at a famous battlefield,” Hancock said.

While Hancock fit in with the ASL community quickly, communicating with others on campus was a tougher transition.In a short amount of time, he had to use more of his voice and less of his hands.It was a tough obstacle to overcome, but the people he met helped ease that transition.

Through WKU’s ASLO, Hancock met Rebekah Thompson, a graduate assistant and park ranger at Mammoth Cave National Park. That’s when Hancock knew he was in the right place.

Thompson has pushed Hancock to his full potential as a person and also as a friend. They have been friends since he first arrived on campus, and they both hold positions in ASLO. Thompson said she loves that Hancock is overflowing with enthusiasm and the way he cares for others.

“My favorite thing about Noah is his compassion,” Thompson said. “It’s a part of who he is. Any time I saw him, he would talk to me and really ask me about my day. Not just an average ‘Hey, how are you?’ type of greeting but a serious want-to-know how I was doing or what was happening in my life.”

Hancock spends most of his time in the ASL lab or hanging out around campus. He also likes to go to the gym and worship at the Wesley Foundation, which is a United Methodist campus ministry located on College Street, a block from Cherry Hall.

Hancock doesn’t only participate in on-campus activities; he also ventures off campus, where he sharpens his sign language, meets new people and visits with old friends.

“It’s fun to be able to sign with new people,” Hancock said.

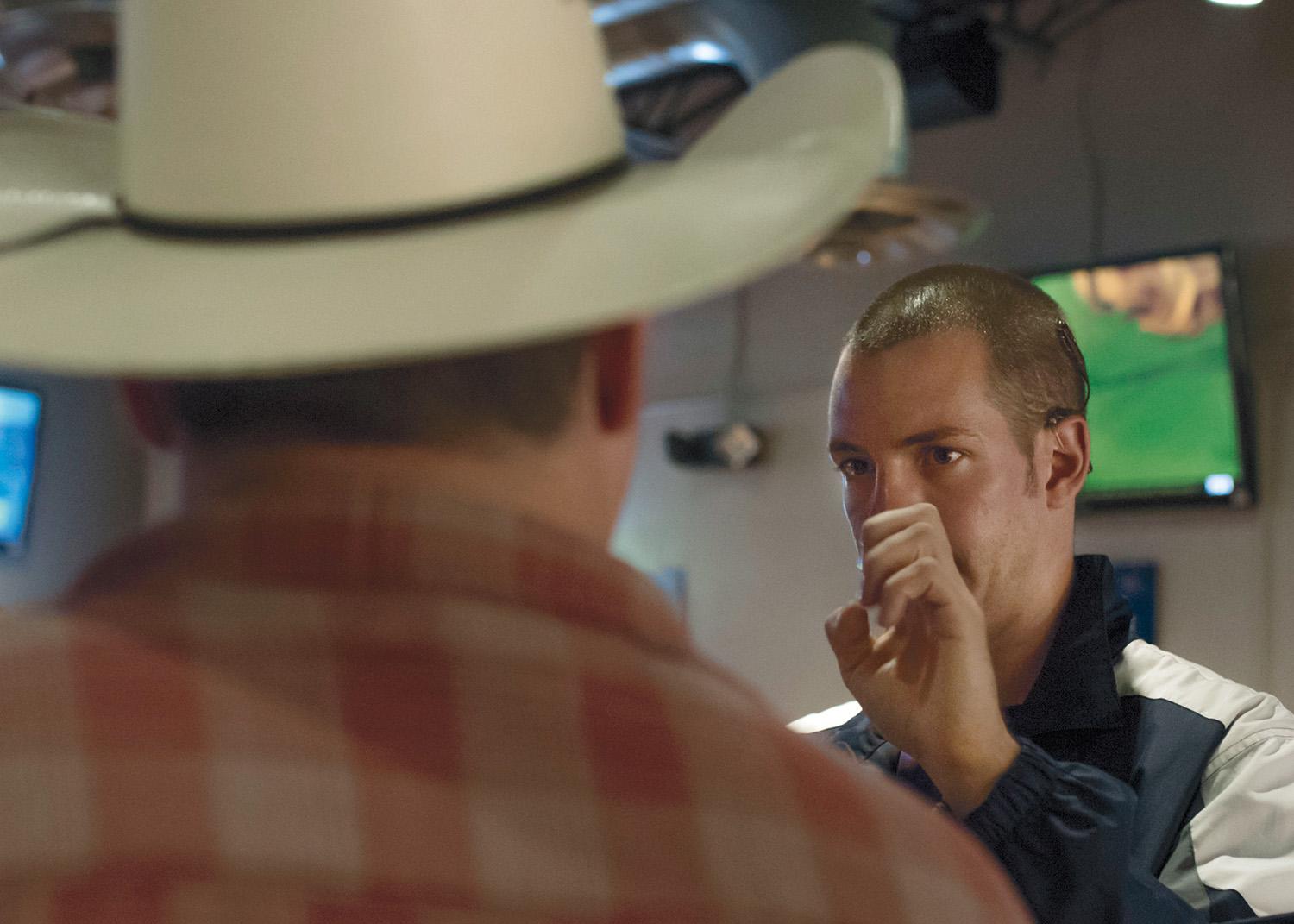

Every first Friday of the month, Hancock travels south to JB’s Pourhouse in Hermitage, Tennessee, where the Nashville chapter of Tennessee Association of the Deaf organizes an event called “Deaf Night Out.”

At “Deaf Night Out,” members of the deaf community converse in sign language. “Voice off” is implemented — a cultural norm and custom in the deaf community, meaning all conversations are held in sign language.

In the ASL lab on campus, “voice off” is strictly implemented so that students can come to study and finish their sign language homework without vocalization. This encourages students to fully engage in their work, and it helps develop improved expressive and receptive skills.

Offering a smile and a sign or two to follow, Hancock is no longer the shy kid in class, and many of his classmates refer to him as being a bright spot in their day. Clay City junior Hayley Wheeler, who studies speech pathology and ASL, said Hancock gives people a new perspective of the deaf community.

“I think it’s wonderful that he can offer so much wisdom to people who might be ignorant to the struggles and the want to be seen as perfectly able in a hearing world,” Wheeler said. “He causes me to be a better human to every human, no matter what.”