There is another side to President Gary Ransdell’s legacy that should be told. The Hill and its people look radically different today than they did two decades ago. The man who rebuilt WKU did so according to his vision — but at what cost?

In August 2015, Gary Ransdell stood on stage in front of a crowd of WKU faculty and staff at the annual presidential pep rally called the Fall Convocation.

Ransdell praised Gordon Emslie, the former WKU provost, who was reassigned to faculty status after five years as the university’s chief academic officer. Few in the crowd applauded as Ransdell articulated Emslie’s “successes.” Some folks cheered a little — but why was not clear — and Van Meter Hall remained mostly quiet, save for Ransdell’s rolling voice.

A little more than five years earlier, Emslie and David Lee — then Dean of the Potter College of Arts & Letters — became finalists for the provost job. Emslie got it.

But in 2015, when Ransdell introduced Lee at the convocation as provost, replacing Emslie, the hall erupted in applause.

“Next week, (Emslie) begins his well-earned sabbatical before assuming his teaching and research duties as a full professor in physics and astronomy in January (2016),” Ransdell said. “Thank you, Gordon.”

With that, Ransdell ended a five-year Emslie experiment met with faculty and staff disapproval. This moment of sobriety kick-started a year of harsh truths for Ransdell.

In the 2015-2016 academic year, Ransdell faced: a new governor hell-bent on gutting support for higher education; a $1.4-million dip into reserves to cover a budget shortfall; a $6 million budget cut; a foundation that’s losing money; declining enrollment; grief over insubstantial raises for faculty and staff for the better part of a decade; and a series of annual workplace surveys that show growing dissatisfaction with his leadership.

On Jan. 29, Ransdell threw in his red towel and announced his retirement.

“My last day in office will be June 30, 2017,” wrote Ransdell in his retirement email. “As provided in my contract, I will then begin a six-month sabbatical leave from July 1 to December 31, 2017 — at which time my employment at WKU will end.”

When Ransdell started as president in 1997, he made $149,000. In 2016, his salary is $427,824.

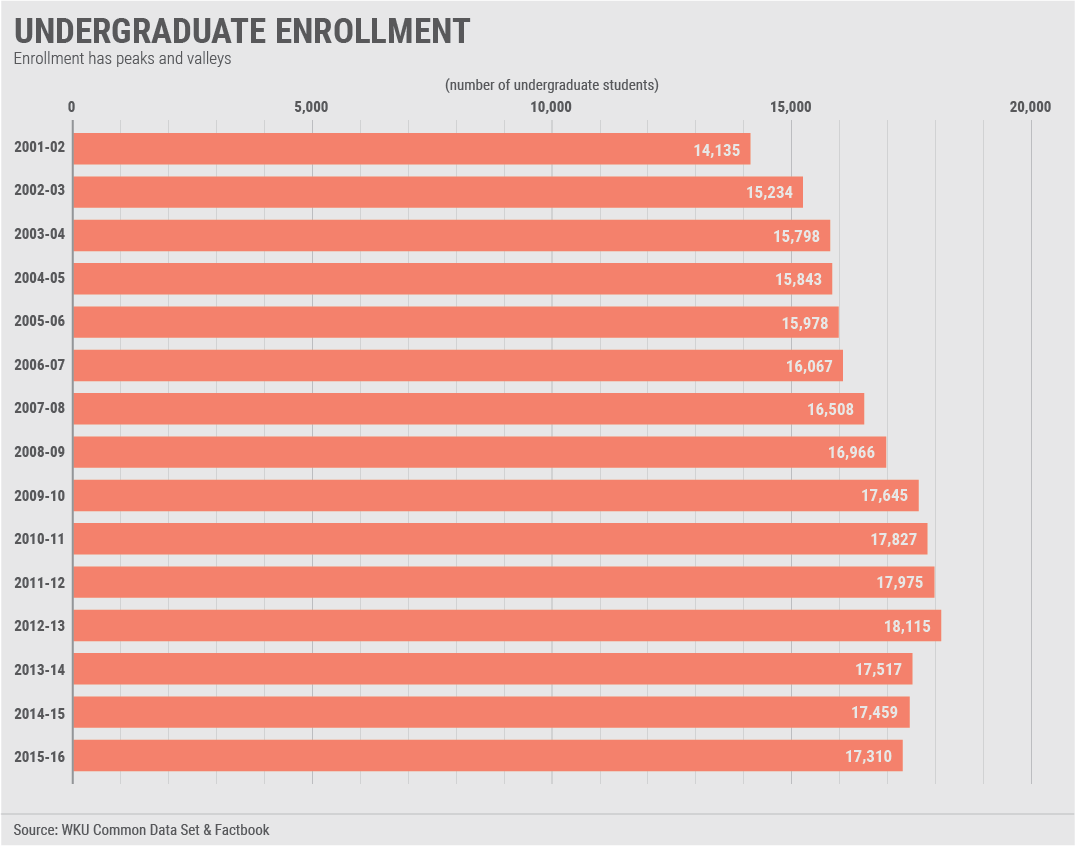

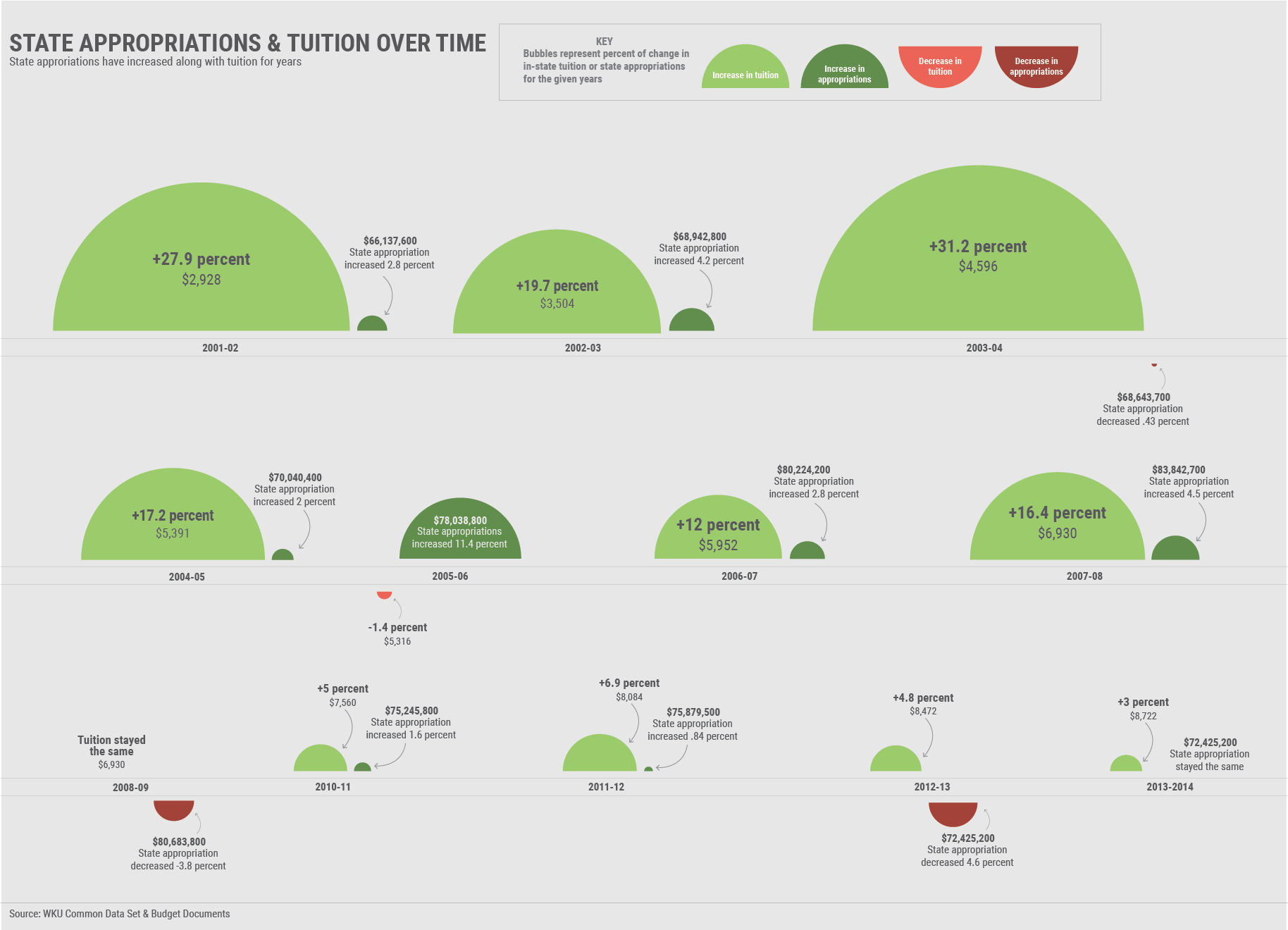

During the past 15 years, WKU spent lots of money growing. But in 2008, the university started getting less cash from the state. WKU started tinkering with admission standards and continued the previous decade’s growth in enrollment. When it comes to the annual budget, enrollment drives revenue.

“We had to create the budget capacity to do things that needed to be done, and 50 percent more students helped create that budget capacity,” Ransdell said.

In 2012, Emslie tightened 2009’s loosened admission standards. Undergraduate enrollment took its first dive in more than a decade, dropping from 18,115 to 17,517. The freshmen class of fall 2013 had better ACT scores, but overall retention hardly changed. Meanwhile, WKU’s “Age of Construction” was peaking. In June of 2012, WKU took out a bond for $35.8 million to pay for phase three of renovations to the Downing University Center. The university’s long-term debts totaled $175.6 million.

Today, faculty salaries fall well below benchmark after eight years of virtually no raises, and a proposed 3 percent increase for the 2016-2017, while a step in the right direction, is just that — a first step. Meanwhile, in-state tuition has nearly quadrupled since 2000 — from $2,209 annually to $9,482.

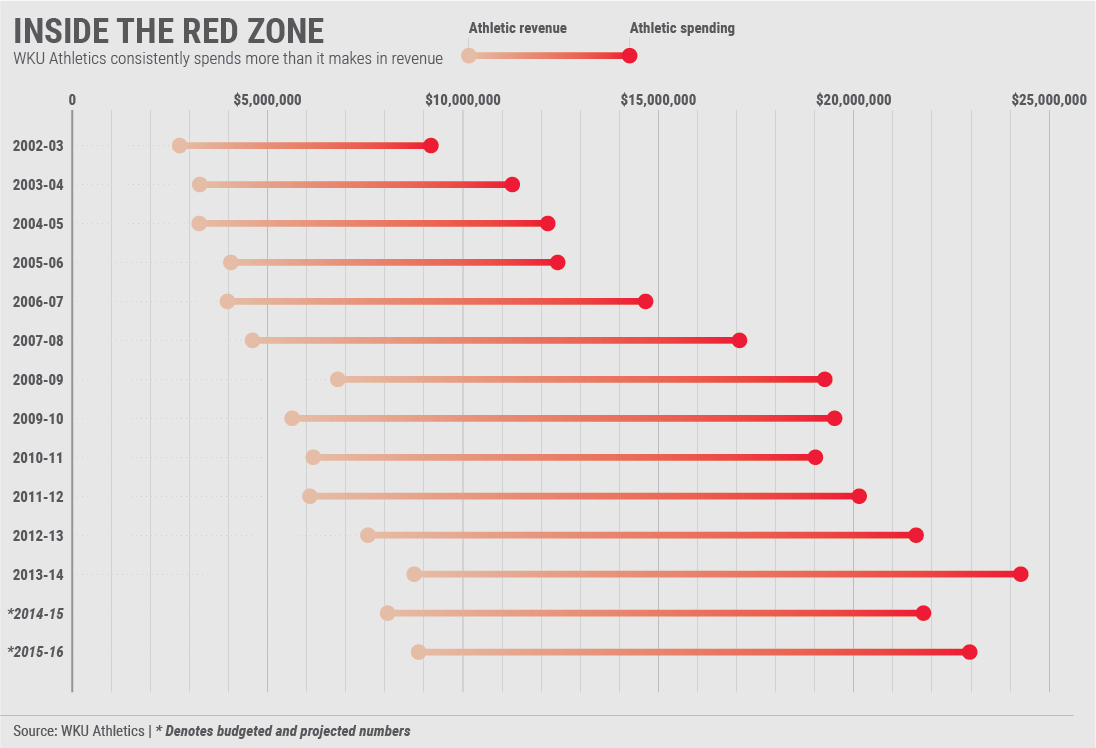

Athletics spending went from $19 million in 2010 to a projected $22.9 million in 2015, WKU budget documents show. The football team’s budget is $6.4 million in the 2015-2016 budget. It includes $500,000 for team travel costs, $2 million for employee wages and $320,394 labeled “Materials — Contingency.”

The football team finished a successful 2015 season and Head Coach Jeff Brohm got a $200,000 raise — private money, the news media reported. But bottom line: the WKU athletics budget is twice as large as the revenue it produces, regardless of the source of budgeted money.

As a living president, Ransdell earned himself a namesake building on campus. The man has a quote engraved near Guthrie Bell Tower, alongside quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and President Abraham Lincoln. WKU has been celebrating Ransdell’s successes for years. But there is another side to his legacy.

THE NEW MILLENNIUM

In 2000, Ransdell’s fourth year as president, 15,516 students attended WKU, according to WKU’s Office of Institutional Research. Today 20,178 attend. Kentucky residents paid $2,290 a year to attend undergraduate classes. Now they pay $9,482. In 2000, Barbara Burch served as provost. Now she sits on the WKU Board of Regents as faculty regent.

“All of this is not by accident,” Burch told a College Heights Herald reporter in 2000 for an article with the headline “Focus on enrollment and retention starting to pay significant dividends.” The article explained plans to further push enrollment.

“Look at the university’s strategic plan,” she said. “We have goals of our own to increase the number of students.”

In 1999, 49 percent of faculty rated Burch’s provost performance as “poor” or “very poor,” shows the Faculty Work Life Survey from that year. The same year, the WKU Faculty Senate became the University Senate, which meant strengthened administrative control.

Burch stepped down from provost 10 years later after a decade of constant growth at WKU. During those 10 years, undergraduate enrollment increased 34 percent to 20,903 students. In-state tuition increased 230 percent to $7,560 a year. Money granted to WKU from state appropriations increased about 17 percent.

The enrollment management department started targeting that 20,000-student benchmark in 2006. The following year, WKU started selling bonds to pay for construction projects. The university took out $52 million in general receipts bonds in 2007, almost doubling the university’s long-term debt from $67 million to about $115 million. From then on, WKU’s accountants started calling its debts “obligations” on the school’s financial statements.

WKU’s long-term debt now stands at $200 million with a payment schedule ending in 2034, according to the university’s financial statements. Roughly 75 percent of that money is bond debt. For example, transforming Downing University Center into the Downing Student Union added on $35.9 million in 2012. Then WKU took out another $36 million in 2013 to build the Honors College and International Center and put the finishing touches on DSU. In 2016, WKU will pay $13.7 million on long-term debt. Ransdell says that debt is low for a university of WKU’s size, but he’s referring to its size after he became its leader, and it started to rapidly grow.

WKU’s long-term debt now stands at $200 million with a payment schedule ending in 2034, according to the university’s financial statements. Roughly 75 percent of that money is bond debt. For example, transforming Downing University Center into the Downing Student Union added on $35.9 million in 2012. Then WKU took out another $36 million in 2013 to build the Honors College and International Center and put the finishing touches on DSU. In 2016, WKU will pay $13.7 million on long-term debt. Ransdell says that debt is low for a university of WKU’s size, but he’s referring to its size after he became its leader, and it started to rapidly grow.

“You don’t rebuild the campus without incurring some debt in the process,” Ransdell said.

In 2009, a special President’s Task Force headed by Lee proposed renaming the Bowling Green Community College to the Commonwealth College and recommended admitting some students who did not meet WKU’s admission standards. The task force report noted that historically WKU accepted some students who did not meet admission standards.

Both recommendations eventually took hold. The Commonwealth College later became South Campus.

Some applicants with an ACT score less than 15 gained conditional admission. These students needed to take remedial classes at the Commonwealth College/South Campus before they could start earning credit toward a degree program. But would still pay full tuition. An open records request for records on the number of students let in conditionally through the years was denied because “Such documents do not exist,” according to WKU Executive Paralegal Lauren Ossello.

Task force recommendations went into effect in 2010 — the same year Burch stepped down as provost. Emslie got the job.

“I think over time people will come to get to know me,” Emslie told the College Heights Herald after his hire.

They did, and data from the annual Faculty Work Life Survey administered by the University Senate shows that they didn’t like what they learned.

CASH MONEY

The biggest chunk of WKU’s revenue comes from tuition and fees. That title used to go to money from the state. Ransdell usually points to this as an explanation for why tuition keeps increasing.

But a closer look shows that tuition hikes have far outpaced state cuts and did so before state cuts ever began. The first big hit came in 2008, when state appropriations to WKU dropped from $83,842,700 to $80,683,800. Tuition costs had increased every year since 2000 — from $2,290 annually at the turn of the century to $6,930 in 2008. Revenue brought in from tuition and fees increased to $97.9 million from just $40.8 million in 2000, a change of 139.7 percent.

Gov. Matt Bevin’s attacks on higher education further increase WKU’s dependence on tuition. WKU already lets in about 93 percent of applicants, so another tuition hike became inevitable for the 2016-2017 academic year. Tuition is increasing another 4.5 percent.

Gov. Matt Bevin’s attacks on higher education further increase WKU’s dependence on tuition. WKU already lets in about 93 percent of applicants, so another tuition hike became inevitable for the 2016-2017 academic year. Tuition is increasing another 4.5 percent.

The new Kentucky state budget brought a 4.5-percent cut to state money — a loss of about $6 million.

Professors such as Eric Bain-Selbo, the head of WKU’s philosophy department, are worried that people in the university’s liberal arts programs could lose their jobs.

“The overwhelming majority of the budget is faculty salaries,” Bain-Selbo said when cuts were first being discussed earlier this semester. “When you decide to cut state appropriations by nearly a tenth, you’re not going to offset that by cutting down on the number of copies being made.”

Instead, the financial burden is landing on custodians, diversity programs and 23 other sources around campus. WKU privatized custodial and groundskeeping through a contract with Sodexo.

Sodexo, an international company with its North American headquarters in Maryland, has faced repeated student protests at universities throughout the U.S. for years. It’s work on U.S. campuses inspires organized protests by United Students Against Sweatshops, the organization’s website states.

WKU is keeping its “International Reach” tagline, but cutting $50,000 from the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, as well as $151,000 from the newly combined ALIVE Center and Institute for Citizenship and Social Responsibility.

Sports spending is also taking a hit after years of steady growth, but one team is taking the full brunt of the cut. The track and field team is losing 50 percent of its budget. Students such as Jenessa Jackson, a junior from Marietta, Georgia, and a All-Conference USA shot put competitor on the track team, are now debating whether to transfer or to ride out a final year with a half-axed track program.

“It’s unfair,” Jackson said. “We are the most decorated team on this campus. We deserve an explanation.”

Ransdell said that balancing the athletic budget is the responsibility of Todd Stewart, the director of athletics. It’s his decision to make, Ransdell said.

“Track has been a terrific program,” Ransdell said. “Unfortunately, it’s not a program that our athletic department is built around.”

WKU spent more than $20 million annually in recent years to prop up revenue deficits in the athletic department budget. Athletics usually generates enough revenue to recoup about one-third of that. For 2015-2016, WKU budgeted $22.9 million for intercollegiate athletics, according to WKU budget documents. It’s projected to make just $8.8 million in revenue, a deficit of $14.1 million.

The biggest source of revenue for WKU athletics comes from “guarantee games” — big payments to WKU from big-time programs that think playing WKU can guarantee a win. This football season, LSU paid WKU $975,000 to play the Hilltopper football, according to public records. WKU lost that game 48-20. University of Alabama is paying WKU $1.3 million to play the Hilltoppers in 2016. WKU will turn around and pay $300,000 of that to play Houston Baptist University.

Another item on Ransdell’s priority list is the Honors College — one of Ransdell’s prime and costly legacies.

Some programs within the Honors College, such as travel abroad funding, are losing $51,000 — a relatively small drop for the program. The Honors College budget nearly quadrupled in the last decade — from $271,117 to $2.5 million today. The latest WKU Factbook brags that the number of Honors College enrollees increased by 42.2 percent in the last five years — from 988 students to 1,405. Now they make up about 8 percent of the total undergraduate student body.

“Most students are on academic scholarships in the Honors College, but again, it raises our academic strength of our campus,” Ransdell said.

The new Honors College and International Center added another $22 million to WKU’s long-term debt.

Space inside the building that was reserved for the Navitas program — nine offices, a reception room, a workroom and a little sign that reads “Navitas Suite” — is all empty. WKU canceled its partnership with Navitas on Dec. 15. During the 2015-2016 academic year, two Honors College academic advisers quit and so did its associate director.

THE ‘GORDON AND GORDON SHOW’

Back in 2011, then Provost Gordon Emslie and then Vice President of Research Gordon Baylis met with students during a series of listening sessions meant to increase administrative understanding of student concerns. The “Gordon and Gordon” show, as it came to be called, traveled to each department on campus.

“There was some squawking that perhaps we came into those meetings with an agenda, but we certainly didn’t have one,” Emslie said.

The “Gordons” shifted out of their roles early last year. On Jan. 4, 2015, Baylis’ job was eliminated. Baylis was reassigned to a position teaching psychology classes. Emslie suddenly stepped down from his provost position in August 2015, and he too took on a teaching position this semester.

Baylis still makes $169,452 a year. Emslie makes $208,321. Barbara Burch, the provost before Emslie, still makes $195,384.

WKU just ended its eighth straight academic year without substantial raises for faculty and staff. The school has fallen behind comparable benchmark universities, shows data collected and published online by Eric Reed, the interim dean of the graduate school and the faculty representative on WKU’s budget council.

“We’ve recommended that we make increasing staff salaries a priority moving forward,” Reed said. “It’s been heard, but whether there is a will to address it is another matter.”

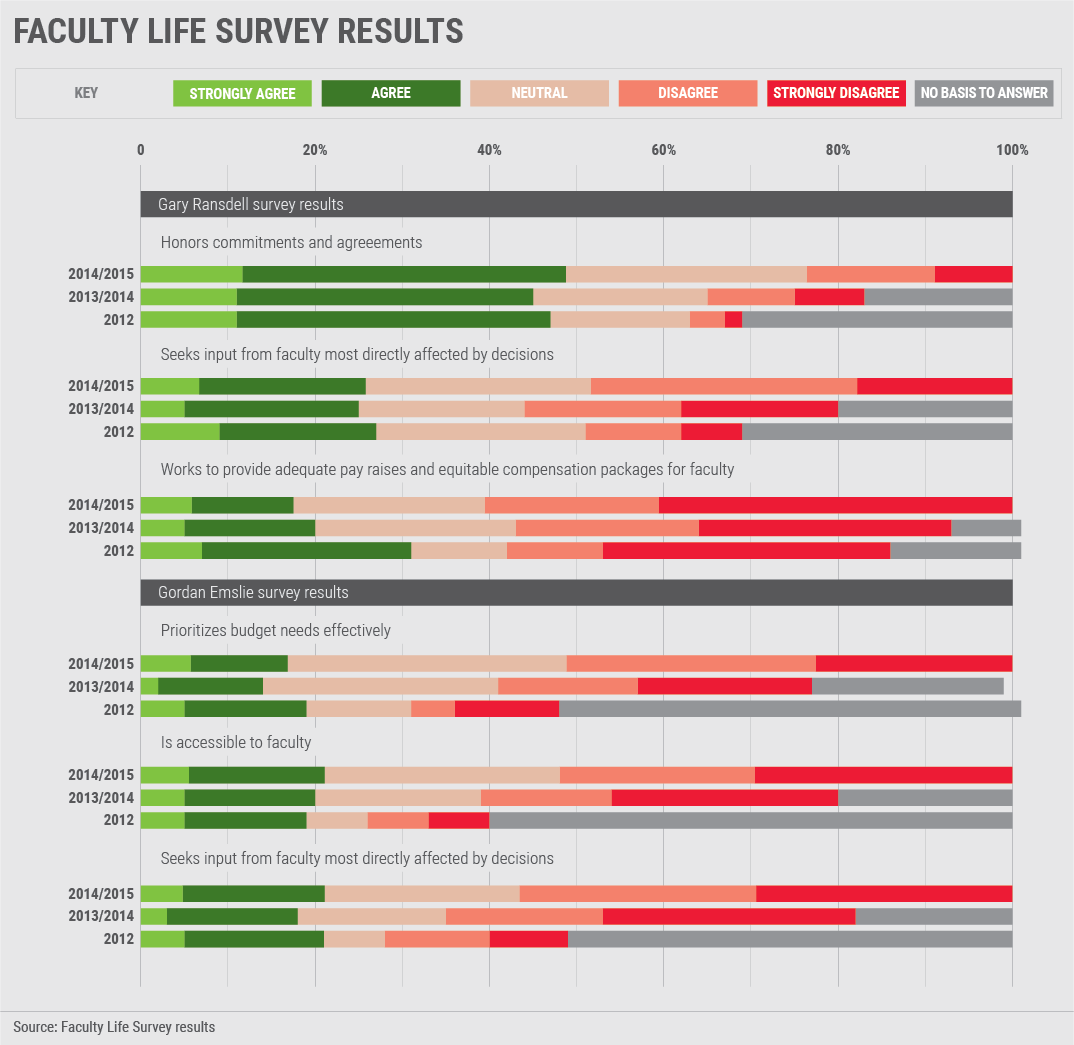

In the 2014-2015 Faculty Work Life Survey, only some 17 percent of faculty agreed or strongly agreed that Ransdell works to provide adequate pay raises. The proposed 3 percent raise for the 2016-2017 academic year — money partially generated from the tuition increase — comes at a time when students fume over tuition hikes.

Weeks after becoming the replacement for Emslie as provost, Lee sat in his office in the Wetherby Administration Building and said that he doesn’t want his term defined by his predecessor. His decision-making techniques differ, he said.

“This is not to say that (Emslie) didn’t by any means, but I have a very collaborative style,” Lee said. “I have a fairly interactive approach to decision making and generating ideas about decisions. I want to be in touch with folks.”

Dr. Larry Snyder, now dean of the Potter College, offered this insight.

“Dr. Lee used to have meetings with students in here all the time,” Snyder said, gesturing around Lee’s previous office in the Fine Arts Center. “I don’t expect that Dr. Emslie was much to do that in his office. It isn’t his style.”

Fifty-six percent of respondents to the WKU 2014-2015 Faculty Work Life Survey said Emslie did not seek input from the people most affected by his decisions. Only about 17 percent said that he properly prioritized the budget. And just 35 percent said that Emslie’s plans reflect the university’s mission. And this was his best set of survey scores since becoming provost. Emslie declined to comment on his survey scores as provost.

Emslie tried for other jobs twice while serving as provost. In April 2014, Emslie was a candidate for University of Central Florida’s provost position, and he applied for the same title at the University of Alabama a year prior.

During a fall 2014 Administrative Council meeting with the College Heights Herald, the paper’s former news editor Trey Crumbie asked Emslie why he was trying to leave WKU. The other administrators covered their mouths and giggled before Ransdell explained to Crumbie that the question was inappropriate.

Emslie spent the fall 2015 semester on sabbatical. The WKU faculty handbook states that administrators seeking sabbatical must apply by Nov. 30 during the preceding academic year. A sabbatical is a paid leave for “professional improvement.” In addition to formally proposing their leave, candidates must have “consistently high job performance” and conduct research.

There is no application on file for Emslie’s sabbatical. WKU paralegal Lauren Ossello said Ransdell’s letter to Emslie detailing his sabbatical terms grants authorization without the standard review process by a sabbatical committee.

“I think he was frustrated and ready to resume his academic career, and I thought the timing was good for the university as well,” Ransdell said last fall. “So we talked our way through it and came to a good, gentlemanly agreement.”

As to what Emslie would do on sabbatical, Ransdell said this back in fall 2015:

“Well, I assume he’s preparing for two things — to return to the classroom as a full-time professor in the spring (2016) semester. It’s not easy going from being a 60 hours a week, or more, administrator to going right back to the classroom. There’s work to be done and class syllabi to prepare. And the other is ramping up his personal scholarly research.”

Emslie earns his $208,321 to teach two physics classes for WKU. Baylis is teaching two Intro to Psychology classes.

Now that Ransdell officially announced retirement, he’s planning his own sabbatical. Emslie kept his original $231,468 salary during his sabbatical. Ransdell will keep his current $427,824 salary for the his sabbatical, which will start immediately after he steps down as president.

As for what he’ll be doing, Ransdell said “We haven’t quite figured that out yet.”

In a 2007 opinion piece Emslie co-authored as dean of Oklahoma State University’s graduate college, he argued that conducting research is directly tied to financial prosperity. The piece references a “human capital crisis” in fields requiring graduate-level education.

“You want your degree to be as valuable as possible,” Emslie told the Herald in 2010. “It’s my job to make sure it is.”

Emslie points to research improvements at WKU as a key accomplishment during his time as provost. He’s proud of the esteem lauded on doctoral programs under his watch, and he’s proud of a student research presentation week that he says exceeded high expectations.

“If I brought anything to the provost position, it was a data-focused decision making model,” he said.

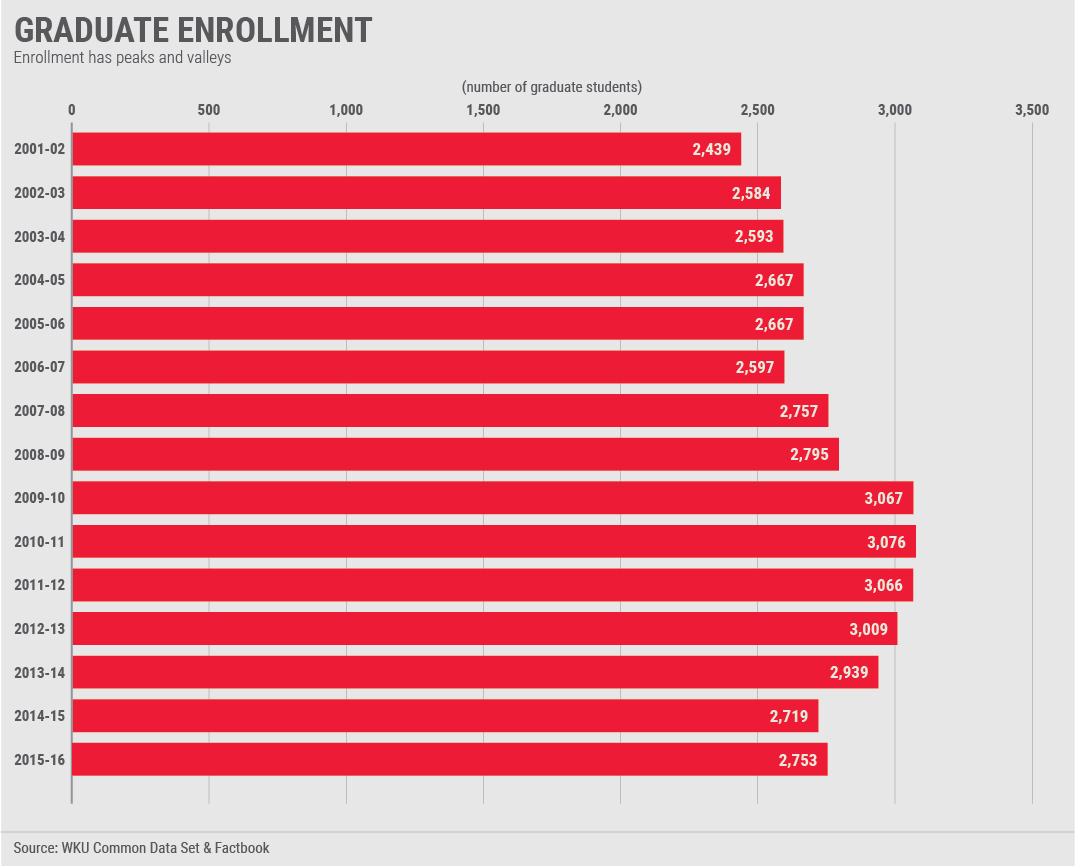

Graduate student enrollment has dropped about 10 percent since Emslie started as provost. The New York Times recently reported that WKU’s graduate program enrolls international students that don’t meet basic requirements but are willing to pay. Ransdell notes that international students are graduating at a higher rate than native Americans, but numbers from the Times piece are still shocking — of 132 students recruited through one program, 106 didn’t meet English language skills requirements.

Emslie’s other efforts include both the aforementioned tightening of WKU’s admissions standards, which was followed by a 598-student drop in undergraduate enrollment in 2013-2014, as well as his expansive (and controversial) bi-term proposal.

THE UNIVERSITY SENATE

Afternoon light streamed through the windows of the Faculty House on Feb. 18, giving its wooden walls a warm glow. Inside, senators took their seats and chattered about campus happenings.

Then with three pounds of a gavel, the meeting began and that warm glow quickly started to cool.

Lee, seated in front of faculty and staff — with campus administrators in the gallery to his right — announced WKU’s new medical school partnership with the University of Kentucky. The contract was already signed.

This was the first the senate heard about the deal but not the first time it heard about a significant deal after it was made.

Back in 2010, controversy stirred over the low representation of faculty on a committee deciding a new faculty benefits plan for the university.

And back in January 2013, it was Emslie’s bi-term plan that had senators simmering.

Emslie’s plan, titled “An Increased Emphasis on Bi-Term Courses at WKU?” proposed “that WKU consider a move to offer a substantially greater number of courses in bi-term mode.”

The senate leadership opposed the plan from the outset, and Emslie abandoned it.

This killed a key money-making component of Emslie’s plan to improve WKU academics. He denied that revenue was a motivator for the bi-term plan. In his proposal he wrote that “the primary motivation is based on academic, not financial, considerations.” In meetings about the plan, he repeatedly denied even thinking about the potential revenue for pushing potentially more-expensive bi-term semesters onto students. He stills denies it today.

But about 90 minutes into a special Senate Executive Committee meeting on July 23, 2012 — a meeting called to hear more about the proposal — Emslie referenced a rather specific dollar amount, the recording of the SEC meeting reveals.

Emslie said: “If students do this and if the fraction that choose to do this accelerated track to graduation and pay more tuition to reduce the total cost of their degree is, say, 10 percent of our students, that’s about $7 or $8 million dollars we got to address some of these items in the action plan with regard to faculty compensation, more faculty and so on and so forth. It puts more of the students’ dollars in the resources students really want.”

The senate’s annual Faculty Work Life Survey reflected respondent concerns about Emslie every year since 2012. The survey includes a series of rating-based questions and a comments section. The questions mostly ask for administrator evaluations, particularly of the president, provost and Board of Regents. All respondents remain anonymous.

When one tries to track Emslie’s and Ransdell’s scores prior to 2012, a large record-keeping problem presents itself. Every year between 2000 and 2011 have vanished from WKU’s archival systems.

WKU Archives and Records Management says it posted every document received from the University Senate and that the senate’s secretary, Heidi Alvarez, is the person to contact for more. Alvarez also was unable to provide the results, and deferred to the senate’s Patricia Minter, chair of the senate’s Faculty Welfare and Professional Responsibility.

Minter said the archival office response was improper, and she also could not provide the documents. She was previously unable to find records of the survey she conducted as the senate chair.

“State archival laws require that the university archives take control after a certain amount of time,” Minter said. “For the archivists to say that it’s the responsibility of Heidi is simply not true. There’s a lot of convenient record keeping at WKU, and I wonder if we’re violating state law.”

WKU replied to a records request for the documents saying they “do not have the results of the survey and no way of knowing if it was actually sent out to the faculty.”

Minter confirmed that the survey is carried out annually and was done so during the documentation gap. So did 2003’s senate chair, Doug Smith. And so did three-year senate chair Robert Dietle.

“Yes, we conduct one every year,” Dietle said. “We’ve always relied on the administration to keep track of those. But it’s my understanding that some have gone missing.”

On the results that are available after 2011, the anonymous comments from faculty respondents are marked “Confidential.”

Survey results from the 1990s that are available on WKU’s archive website include the full text of the anonymous comments section, including comments on Ransdell.

One comment from 1999’s results alluded to Ransdell’s priorities: “Does President Ransdell realize we have an academic component?”

Only 21 percent of respondents believe that academics are the Board of Regents’ top priority, the 2014-2015 survey results show, and 48 percent of respondents think Ransdell doesn’t seek input from the faculty most impacted by his decisions.

WKU denied a Talisman request for access to the comments sections of the 2014-2015 survey, and the denial was supported by the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office after the Talisman filed an appeal. The AG ruled that the documents were preliminary in nature and therefore not subject to open record law.

Recent surveys received about 52 percent participation, Minter said. She said those numbers would plummet if the comments sections were made public, even though no names are attached to the comments.

“There’s a paranoia on this campus,” she said. “A lot of people think Big Brother is watching no matter what.”

The gap in the survey records began when WKU switched from the “Faculty Senate” to the “University Senate” in 2000. The University Senate makeup diminished faculty representation in favor of more administrators including department heads.

The senate hasn’t been quite the same since, many believe.

When the change appeared on the horizon, Edward Wolfe, WKU’s last-ever Faculty Senate chair, told the Herald “I think there is an intimidation factor going on.”

JUMPING SHIP

Ransdell’s fall 2015 convocation remarks came to a heartfelt close — but one that did not necessarily align with his spending priorities.

“You are the lifeblood of this university,” Ransdell said. “Your wellbeing is rivaled only by the wellbeing of our students, and I’m proud to work with you.”

He spoke those words of praise a few months before Bevin won the Kentucky gubernatorial race and before massive budget cuts loomed over higher education in the Commonwealth. Those words came a half-year before he made multiple trips to Frankfort to desperately lobby for more higher education money.

“I intend to spend whatever political capital I may have built up over the years in pursuit of what higher education needs in both dollars and knowledge of our values,” he wrote in his retirement announcement email.

But now that the end of the year and full budget news has reached WKU, Ransdell is facing criticism and rowdier crowds.

On April 28, 2016, administrators lined the front the DSU auditorium. They looked uneasy. The auditorium was mostly full. Ransdell was watching his watch. He had a 4 p.m. meeting. A single light near the front of the auditorium — one of the newest structures on campus — was flickering on and off.

News of the cuts came out the day before in an email to faculty and staff. Students were left out but soon started to catch wind of the news. The next day in that tense forum in the DSU auditorium, one student asked Ransdell why he isn’t taking a pay cut. Ransdell, after dodging the question a few times, replied: “Because I said so.”

At 4 p.m., Ransdell left the auditorium, leaving Lee in charge. The event soon came to a close and the crowd dispersed. Lee stuck around fielding questions from students for a little while longer. As for whether there is any reason to believe that this would be the last round of budget cuts, Lee said: “I honestly have no idea. Ransdell says so. I have no idea.”

Ransdell — a 65-year-old with graying hair, small-framed glasses and a trademark “Hi, how are ya?” — leaves a complex and conflicting legacy at WKU.

On the one hand, Ransdell completely revamped the university since 1997. The campus has changed radically in terms of cosmetics, enrollment and governance. He’s kept WKU cheaper than University of Kentucky and University of Louisville, but more expensive than the rest of Kentucky’s schools. The Honors College has brought talented students to this university, and WKU’s “international reach” has improved Bowling Green’s overall cultural diversity. And he has raised a tremendous amount of private money for the university.

But among faculty, there is a documented tension over his priorities as president when it comes to things such as faculty compensation, athletics spending and building projects. It appears that previous members of his administration find high paying jobs teaching small course loads, regardless of their performance. His building projects accrued a lot of debt to invest in an expansive future, yet it looks like budget cuts will shrink WKU’s academia.

On Monday, April 25, 2016, Ransdell sat in the President’s Office building. He wore a white shirt on a red tie and a red-faced watch to match. He warned, correctly, that news of academic cuts would come on Wednesday.

Back in 2007, Ransdell said that the transformation of WKU that he envisioned when he first became president was not yet complete. His contract was extended to 2022, and he said that his dreams for the university would be accomplished in that span — a 25-year presidency.

“True transformation doesn’t occur in 10 or 15 years, but 25,” he said. “You bet.”

But now, Ransdell is preparing to leave the Hill five years short of his self-mandated quarter-century. He smiled in his chair and said “I was a younger man back then,” with a laugh.

“You have to be all in on this job,” he said. “I’ll be 65 in October, and I’ll be 66 for my last year. Twenty years on the job, I’ve determined, is a pretty good number. We’ve done the best we could, and it’s time to turn it over to somebody else.”

Graphics by Cameron Love.