The Talisman amended this story on Feb. 9, 2017 due to inaccuracies. We regret the errors that were published.

It was fairly quiet inside the Gary Ransdell Hall Auditorium. The light sounds of muffled laughter, letters clicking on phone keyboards and muted conversations came into the room as students and community members entered, looking for rare empty seats among rows of packed chairs.

The night’s event was a lecture from Jose Vargas, an outspoken immigration activist. Outside the auditorium, on news stations and the internet, in Congress and city council meetings, the conversation was much louder.

“We are going to build a wall,” Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump said. In the fall, Trump promised that if elected, he would deport 11 million undocumented immigrants “so fast your head would spin.”

Days after the lecture, Facebook was buzzing with posts about the Syrian refugee crisis. Congress voted to slow Syrian immigration to the United States, despite President Barack Obama’s threat to veto the measure.

Although he was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, awarded documentarian, and Time magazine cover person, few in the audience recognized Vargas. He stood to the left of the stage in an unassuming plaid shirt and blazer with his hands in his pockets.

Before hearing he was coming to campus, Somerset junior Erick Murrer did not know about Vargas. He chose to attend the event because he said he had experienced the difficulties of immigration.

Murrer’s partner, Robert Hua Zhao, was a Chinese native and immigrant to the U.S. Zhao moved to New York City after graduating from WKU in 2014 to look for a job, but he had trouble finding work and health care because he was not a U.S. citizen.

Vargas spent his career collecting stories like Murrer’s and Zhao’s. His nonprofit, Define American, collected videos of Americans both documented and otherwise — defining their perception of what it meant to be an American in order to change the way immigration was talked about in the U.S.

“Stories transcend the fiercely partisan and politically toxic atmosphere,” Vargas said. “You can’t really argue with someone’s story.”

The lecture began with 10 stories. In a short video, undocumented Kentucky students recounted their immigration stories. One word echoed like a litany through the room: home.

“This is where my friends and family are,” one undocumented student said. “This is where my dreams have come true.”

Another student attended WKU. “I am a proud Hilltopper and I am a Kentuckian,” he said.

Perhaps the most powerful story Vargas shared that night was his own. When he was a 12-year-old in the Philippines, Vargas hugged his mother goodbye for the last time. She was sending him to the U.S. to visit her parents, who were naturalized citizens. What he didn’t know, however, was that he was here to stay.

Vargas said whenever he applied for jobs, he would always check the box marking him as a U.S. citizen. This tactic helped him get his first job at Subway, and eventually worked for his careers at The Washington Post and The New York Times.

“I didn’t see a problem marking that box,” Vargas said. “I thought citizenship was something you earned, and I was going to try to earn it.”

Vargas “outed” himself — a term he specifically chose to represent his dual identities as both undocumented and gay — as an illegal immigrant in his 2011 New York Times essay “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant.” For weeks after, he waited for a call saying he would be deported.

None came.

He even called the Department of Homeland Security himself.

“Why haven’t I heard from you?” Vargas asked.

The woman on the other end of the line put him on hold, then returned and said, “The United States has no comment.”

Vargas said “no comment” was a metaphor for how the U.S. viewed or, more accurately, did not view undocumented immigrants. This lack of visibility inspired much of Vargas’ work and advocacy. It also inspired his decision to visit college campuses.

“There are undocumented among you,” Vargas said. “We are your teachers, doctors, nurses, neighbors.”

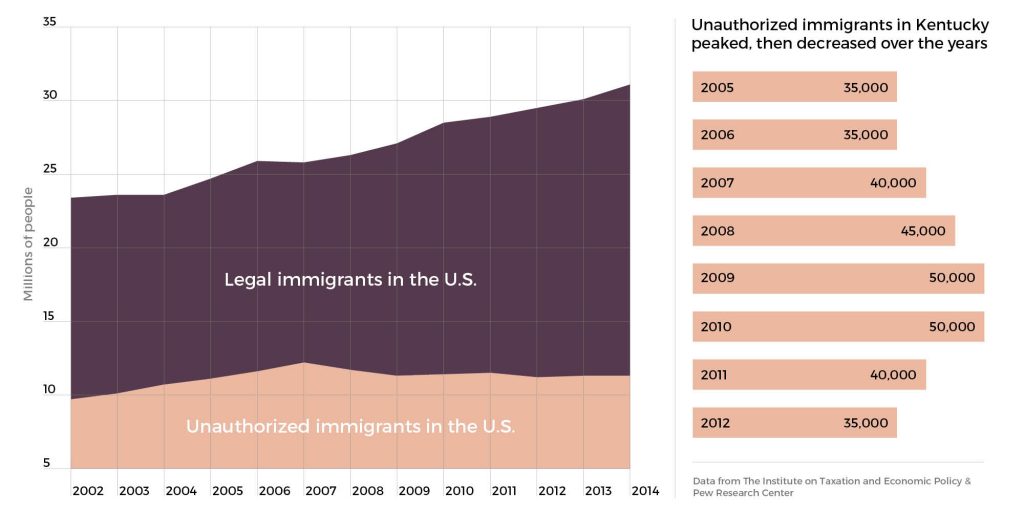

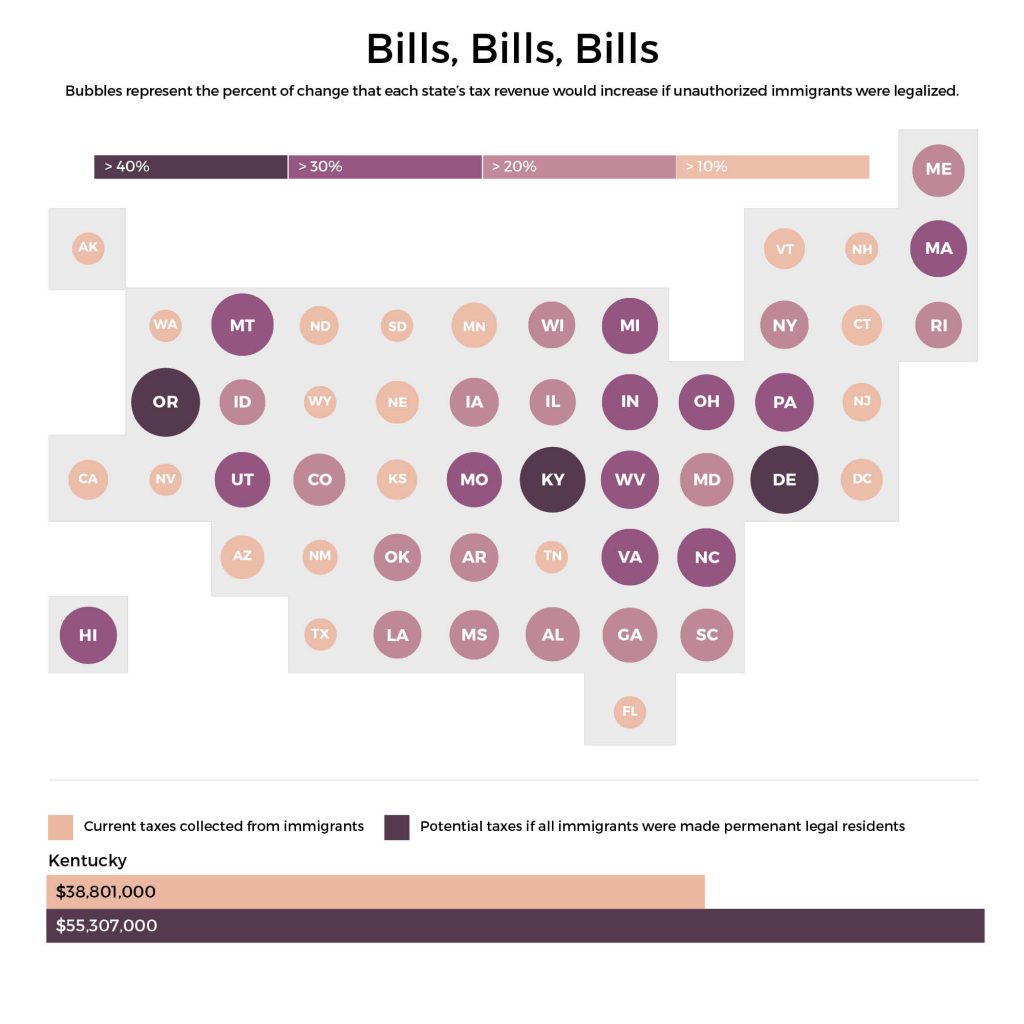

There were 25,000 undocumented immigrants in Kentucky alone, according to estimates from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Vargas said these immigrants paid $40 million in state taxes in 2012. If they were made naturalized citizens, he claimed they would have contributed $55.3 million.

There were 25,000 undocumented immigrants in Kentucky alone, according to estimates from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Vargas said these immigrants paid $40 million in state taxes in 2012. If they were made naturalized citizens, he claimed they would have contributed $55.3 million.

“Immigration is about facts,” Vargas said. “We have to resist the overly simplistic narrative.”

Vargas considered the wait-your-turn-in-line misconception the most critical. If you don’t have a parent or spouse naturalized in the U.S., and you aren’t coming to accept a job offer, it’s nearly impossible to immigrate legally, he said.

Even for people lucky enough to qualify, the “line,” or waiting list, was incredibly long. For those from the Philippines applying in 2015 for family-based visas, Vargas said the wait was 24 years.  Louisville senior and Colombia native Jessica Henao Barragan waited 10 years to immigrate legally to the U.S. She sat on the front row during Vargas’ lecture beside other members of the Hilltopper Organization for Latin American Students.

Louisville senior and Colombia native Jessica Henao Barragan waited 10 years to immigrate legally to the U.S. She sat on the front row during Vargas’ lecture beside other members of the Hilltopper Organization for Latin American Students.

During the Q&A following the lecture, Henao Barragan’s hand shot up. Unlike others who asked Vargas questions, Henao Barragan addressed the audience.

She spoke about how her family applied for a green card when she was 8. They waited 10 years before their application was accepted.

“In high school in Naples, Florida, my teacher asked me what I thought about illegal immigration,” Henao Barragan said to the audience. She told her teacher that everyone should come legally. “If I had to wait, then they should, too,” she said.

This all changed when Henao Barragan moved to Nashville for her second semester of high school. While there, she met undocumented immigrants and learned about their struggles. Many became her close friends. Eventually, Henao Barragan said she recognized the advantage her father had as a Colombian professional with money and networks to help him.

“A lot of people don’t have that,” Henao Barragan said. “They are trying just to survive and feed their families.”

Henao Barragan said she was now a “true believer in immigration reform.”

Vargas ended the evening by urging WKU students and community members to ask harder questions about immigration and U.S. foreign policy.

Into the quietness that began the night, into the raging debate surrounding immigration in our country, Vargas urged attendees to project their voices.

“People have a terrible misconception that they can’t do anything about this,” Vargas said after the lecture. “But immigration is stories, and everyone needs to tell theirs.”