It was Sept. 7, 2010, and several men fitted in black suits tucked one-of-a-kind bolo ties neatly beneath their button-down collars before lining up as honorary pallbearers for the funeral of a man who had become a constant in their lives — up until his death. The bolo ties were gifted by this man, and the pallbearers were expected to keep them in his honor. Self-titled as the “Bolo Brigade,” the pallbearers swore a blood oath that day to wear bolo ties henceforward, and one man in particular did just that.

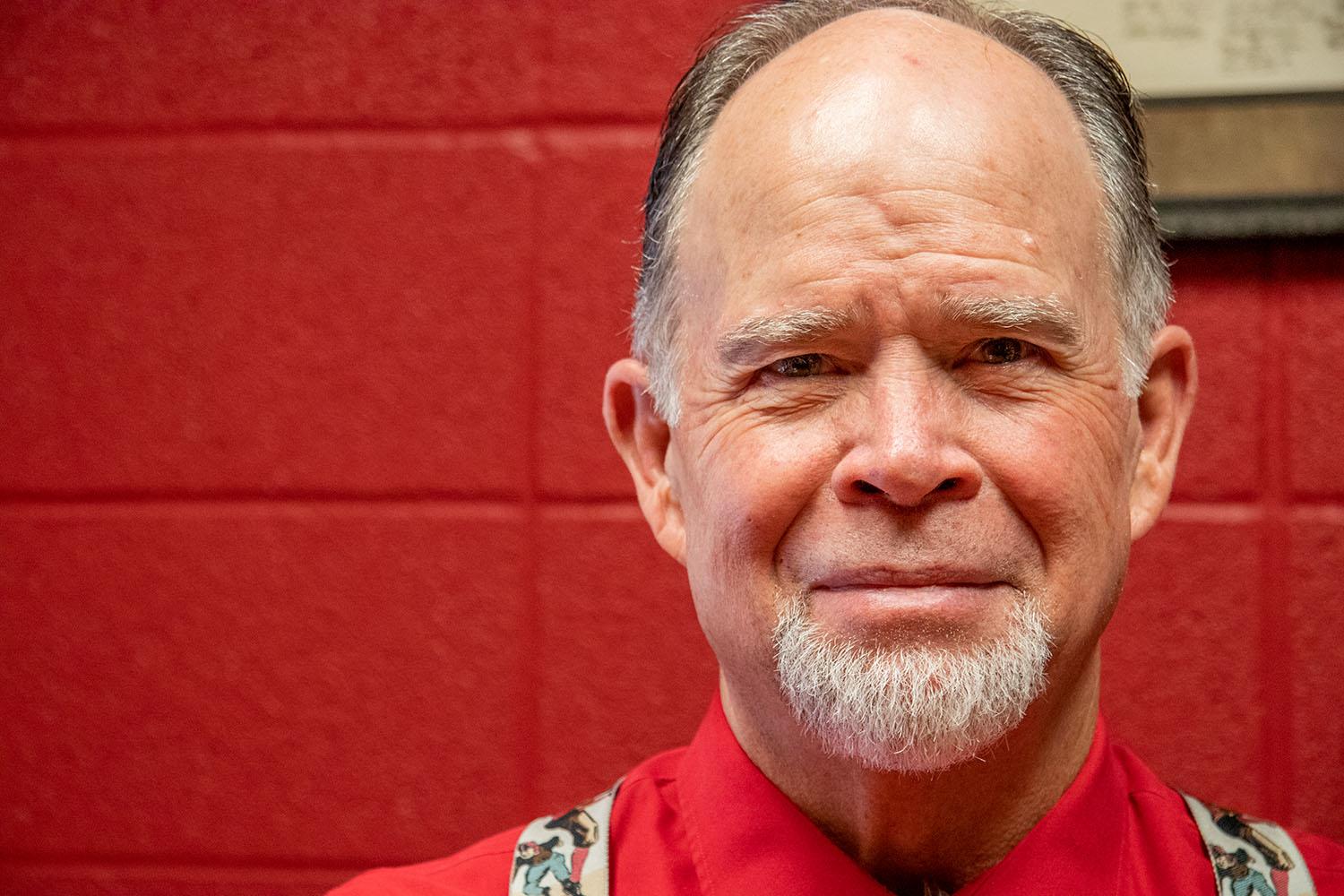

Chris Derry is known throughout WKU’s marketing department as the man whose daily attire is unwavering. The marketing professor wears suspenders and a different bolo tie each day because to him, a promise is a promise. On the first day of class each semester, the Barnesville, Ohio, native tells his students a story of the funeral he attended as an honorary pallbearer and how he left it as strict member of the Bolo Brigade.

That first tie Derry received from the funeral, a braided leather cord threaded through a pink agate, is the tie he wears on the first day of class each semester. Although there wasn’t any blood involved in their blood oath, the gusto behind it was no less impactful for Derry, who thinks of his old friend every time he gets ready for work in the morning.

“He was an inspiration to me,” Derry said.

The man who willed away bolo ties after his death was Ralph Smeed, a “dyed-in-the-wool” libertarian who wanted people to think about the world around them and act on their beliefs. Smeed was native to Caldwell, Idaho, and was 88 years old when he passed away from pancreatic cancer. Up until his death, the prickly activist preached to anyone reachable by word of mouth — or word of highway reader board — that Americans need to question everything.

“He spoke his mind,” Derry said. “He didn’t care whether you liked it or not — in fact, he wanted you to disagree with him.”

Smeed believed the bigger the government, the smaller the citizen. In a 1975 interview with Idaho Public Television, Smeed was stern-faced when he spoke about “institutions of freedom” with a tobacco pipe habitually placed between his lips. While his boldness never faltered, his stature became much smaller as he neared the end of his life.

A Republican delegate to the convention that nominated Barry Goldwater to the presidency in ‘64, Smeed believed people are “infinitely more complicated” than total government regulation can allow. Goldwater lost that election, but Smeed continued advocating with confidence.

Derry and Smeed’s relationship began in 2005 at a conference held in Denver for think tanks that were interested in educating people about how free markets work. Smeed started the first Idaho free-market think tank in ‘77 called the Center for the Study of Market Alternatives, a state public policy research entity.

Derry said Smeed attended conferences for think tanks to coach young people who were interested in starting their own. Seeing Smeed at the conference, Derry was compelled to go shake his hand — that was the beginning of a five-year friendship.

Smeed treated his friendship with Derry matter-of-factly. He would call Derry daily, read him the Declaration of Independence and discuss the importance of a representative democracy. These conversations inspired Derry to keep a print of the doctrine hanging in his office at WKU.

Imitating the shaky and slow voice of an elderly man, Derry said Smeed would call him and say, “Chris, what have you done to save the republic today?”

“He was a curmudgeon,” Derry said. “If you look up the definition of curmudgeon, that’s Ralph Smeed.”

Smeed influenced Derry because of these calls. However, Derry’s contributions to the republic began much earlier in life.

In ‘89, around 15 years prior to Derry and Smeed’s first meeting, Derry drove to Dallas in his wife’s Mazda RX-7 to watch a football game with his buddies. His wife hated when he drove her car, but that day was different. A football was spinning midair, and Derry had his arms outstretched as if to catch its fall when he was abruptly instructed to run a memory disc on the computer shoved in the corner of the room.

Soon after, Derry was introduced to the contents of the memory disc: a behavior assessment that evaluates a person’s dominance, influence, steadiness and conscientiousness, called DISC. A man in need of money and in search of work, Derry was asked to be a distributor of DISC for companies and took the job.

DISC assessments help companies find employees who would best fit their mission and help people learn what career fields they would succeed the most in. Eventually, Derry decided to produce the assessments for people himself. He started his own consulting firm, which has been running for 30 years.

Along with the DISC behavior assessment, Derry added two more assessments to his portfolio. He added a motivation assessment based on the philosopher Eduard Spranger and a clarity of thinking assessment based on the philosopher Robert Hartman, which shows what people value in their lives.

“That’s one of my biggest passions: trying to understand people because they’re all different,” Derry said.

That was just one of the beliefs Derry and Smeed had in common.

Smeed believed the strength of an economy stems from people thinking clearly about themselves, their neighbors and their property. One way he challenged his neighbor’s beliefs was through his highway reader board, which stirred up an opinion in nearly every car that drove down Interstate 84 near the Franklin Road interchange in Caldwell, Idaho.

At one point in time, the reader board read, “Election Analysis — Under the Republicans, man exploits man: under the Democrats, just the reverse.”

In 2003, two years prior to meeting Smeed, Derry created Kentucky’s first free-market think tank called the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions.

Another member of the Bolo Brigade, Wayne Hoffman, was a reporter at the Idaho Press Tribune in ‘96 when he first met Smeed. Smeed found Hoffman’s reports biased and phoned him to express those sentiments. After firm objection and affirming his objectivity as a reporter, Hoffman lost the battle and owed Smeed lunch. The two went on to have many lunches, dinners and breakfasts, and they became good friends.

“He would call me almost daily to ask me about various issues that we were working on,” Hoffman said. “He wanted to see impact and results from conversations we were having, rather than just ‘meeting, eating and retreating.’”

Smeed continued to school Hoffman on the issues of the day and promote his values of limited government, free society and free economy, while also remaining skeptical of those around him.

“Interesting if true” was an expression Smeed passed on to Hoffman.

Hoffman does not wear bolo ties every day like Derry, but he does occasionally in Smeed’s honor.

After Smeed’s death, the Bolo Brigade decided eulogizing him would be against his wishes and would consist of the meeting, eating and retreating that frustrated Smeed. Smeed had money left in his foundation and wanted it to be used quickly for research that reflected all of his endeavors.

Derry served with other friends of Smeed to disburse Smeed’s assets quickly after his death.

“There are not very many people who inspire you, and Ralph was one of those guys,” Derry said.

Saving the republic doesn’t stop with helping companies find their niche and investing millions of dollars to honor a late friend. Derry’s classes at WKU are filled with knowledge of markets and a desire to help students’ find themselves in an individualistic world.

When Derry began teaching, he brought his three assessments on behavior, motivation and clarity of thinking to the classroom and began evaluating his students. He believes guiding students is his duty as a teacher.

“What I like to do is help students understand themselves and then help them find a path that will fulfill them,” he said.

Derry uses the clarity of thinking assessment to keep a close eye on his students’ mental health stability. Many years back, he experienced a student’s death due to drug overdose, and while he knew it was outside his realm of responsibility, he couldn’t help but think that the student’s low assessment score could have told him something sooner.

Soon after those events, two students had the same low assessment results. Derry felt compelled to meet with the women and ended up helping them receive therapy for traumas that were dominating their lives.

“It’s a way of understanding how a student feels about him or herself and their role as a student,” he said. “It’s powerful — I’ve used it ever since.”

Derry said he has built genuine relationships with many of his students, but only a few have taken part in his bolo story.

“When they get to know me, they’ll ask about a bolo,” he said.

Heather Gosebrink, WKU alumna from St. Louis, spent much of her time as a marketing major under Derry’s wing. She remembers taking Derry’s assessments twice — once before he had recommended her for a sales internship and once after she had completed it.

Selling life insurance in rural, low-income homes in parts of Kentucky and Tennessee was not a job Gosebrink thought she was prepared for. Sitting on the pull-out steps of mobile homes and knocking on doors caving in, Gosebrink found herself surrounded by a hospitality she was unfamiliar with.

“Where I’m from, people don’t let you in when you knock on their front doors,” she said.

Gosebrink’s assessment results had drastically changed following her summer internship.

Days driving into cow fields and — almost — driving into creeks, Gosebrink made many phone calls of fear and disappointment to Derry, who would tell her to step back and change focus.

“Just getting to sit down with him and connect with him, no matter who you are, is amazing,” Gosebrink said.

When Gosebrink graduated, she gifted Derry a pink and blue bolo tie, which he keeps hanging in his office “for emergencies.”

Today, Derry has around 50 bolo ties, including one with a buffalo nickel attached to a piece of cut antelope horn. He buys them antique.

“I wear them every day because I get to think about Ralph every day,” he said. “I want to keep him top of mind.”

Derry believes all students should go on to impact the world, the economy, the free market and make a personal profit — they are “infinitely more complicated” than one entity can control.

“When Ralph said, ‘What have you done to save the republic,’ he was saying ‘what have you done to save America?’”

Derry also believes the most important thing for young people to focus on is self-discovery.

“If you don’t think through and examine what your strengths are and what your weaknesses are, then it’s hard for you to deal with other people who are different than you,” Derry said before he quoted Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”