The first time Brent Andrews saw somebody die in front of him was in November 2017. The 22-year-old nursing student was riding along in an ambulance as part of his training to become an emergency medical technician when his radio beeped.

“CPR in progress,” the dispatcher announced.

Andrews, a Franklin, Tennessee, senior and his accompanying paramedics responded to the call, at which point they received more information from the dispatcher and prepared to drive to the middle-class suburb where a man in his 50s had collapsed from a complete blockage of his main coronary artery. This type of catastrophic heart attack is nicknamed the “widowmaker” because of its extremely low survival rate.

When Andrews and his fellow crew members arrived at the scene, the man’s family led them to the bathroom where the man had collapsed. Andrews’ job was to help get the man on a stretcher and into the ambulance as quickly as possible. As the ambulance sped to the nearest hospital, Andrews was responsible for breathing for the man because he could not breathe for himself. He pumped a bag valve mask attached to a breathing tube once every four to six seconds as other paramedics and EMTs administered CPR and gave him doses of various drugs in attempts to save his life.

Their efforts were in vain. The man was pronounced dead 15 minutes after he arrived at the hospital.

“It makes me realize life is pretty fragile,” Andrews said, reflecting on the incident on a chilly Saturday night in October.

Outside his room, his friends Gabe Scarlett and Morgan Hornsby were making potato soup with oven-fresh bread for dinner, and his dog Willow was running around sniffing for scraps. Andrews is the sort of person who loves having people around him. He has curly brown hair and warm eyes that lit up earlier when he caught Morgan stealing a pair of socks from his room.

“Do you want to ask first?” he asked, laughing, before offering her a more comfortable pair.

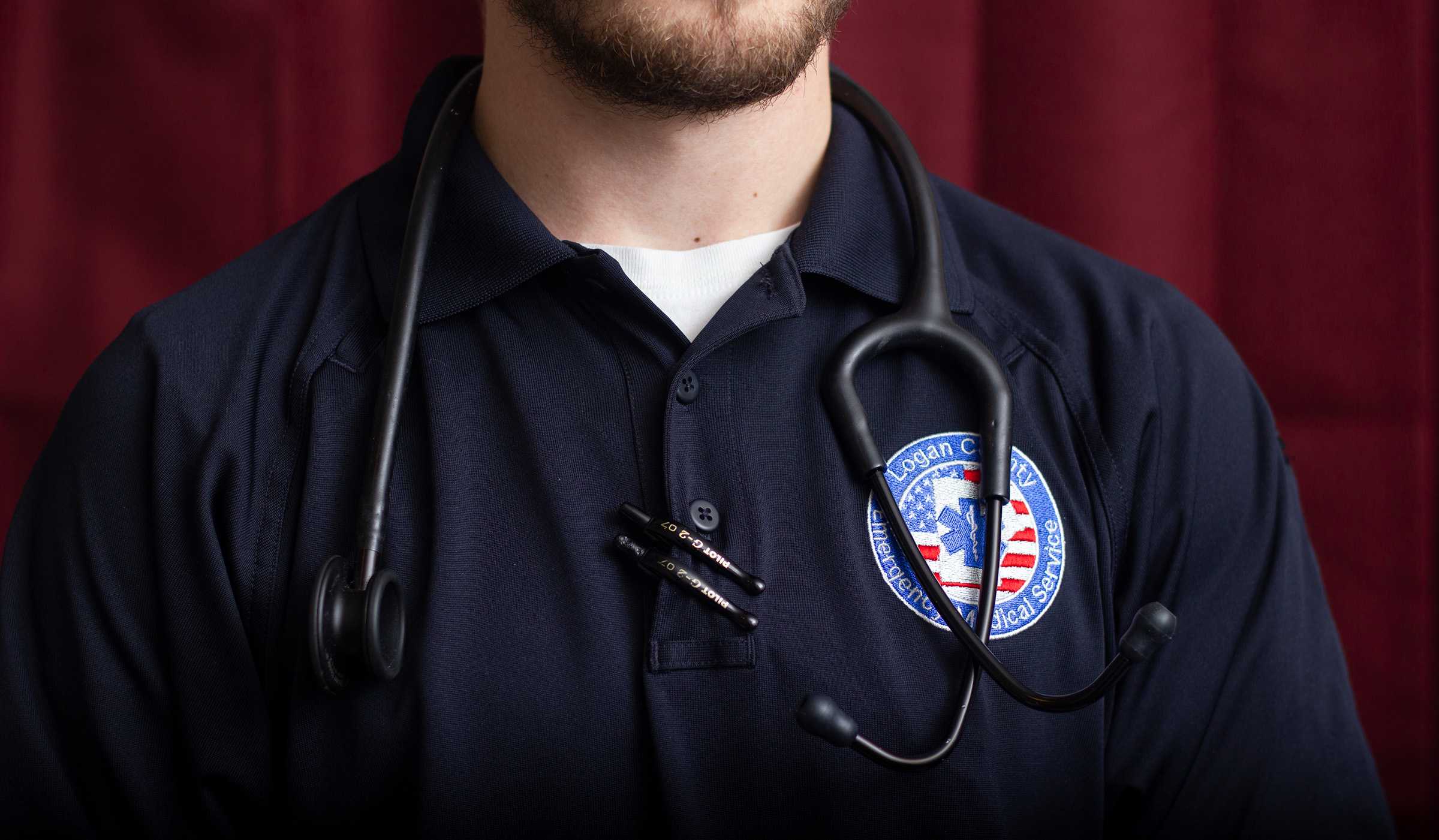

Andrews is often lighthearted, but he also doesn’t shy away from talking about dark and serious topics. Death and sickness are frequent and unavoidable parts of his life as an EMT, nursing student and part-time employee at The Medical Center in Bowling Green emergency room.

“I have seen people who are comfortable dying die and people who weren’t comfortable dying die,” Andrews said. “I want to be someone who’s comfortable with it.”

Andrews usually works one or two 24-hour shifts a week, but that morning, he’d clocked out of a 35-hour shift at 7 a.m. Com-Care, the ambulance company he works for in Logan County, was currently short-staffed because several of their full-time employees were in Florida assisting with Federal Emergency Management Agency relief for Hurricane Michael. These long shifts are not uncommon for Andrews after a long week of nursing classes, clinicals and working in the ER.

Andrews friend and fellow WKU classmate Jordan Frodge, a senior from Maysville, said she and Andrews’ other friends often worry that he works too hard.

“He just sees people in really vulnerable states, and that has to take a toll on him,” Frodge said. “I think we all just wish he would be more mindful about the burnout. He has a whole life of getting to see this stuff.”

The hardest calls Andrews takes as an EMT are often not those involving death, but those in rural Kentucky where patients and their families live in poverty. On his most recent shift, Andrews took a few calls to houses with bed bugs, rain leaking through the ceiling and the smell of mold and animals in the air.

“That’s what’s in my mind today,” Andrews said. “A couple houses I went to yesterday were just pretty bad places for bringing up a kid. You feel for the patients and just everyone else in that situation.”

After a particularly bad call, he and his fellow EMTs and paramedics usually take time to talk about it as a group. Sometimes after a hard shift, he calls his mom or dad, who are both therapists.

“I try to be conscious about if I’m feeling certain things,” Andrews said, adding later, “I’m a pretty emotional person, but I don’t think you need to be detached. I think that’s a misunderstanding.”

Frodge said one of the most unique things about Andrews is his capacity for empathy, especially in the fast-paced and emotionally fraught healthcare field.

“I don’t think many people are as empathetic as he is,” Frodge said. “It’s easy in fast-paced environments like that to see people as materializing in front of you, and when they’re gone, they’re not a problem anymore. But I think he understands that every person he sees has had a whole life before them, and they’re also going to have a whole life after him. He sees them as a complete person.”

This empathy extends beyond his job to his friendships. Later, Hornsby told me Andrews, unprompted, once bought a box of menstrual pads to keep in the house just in case anyone needed them. Hornsby ran to the bathroom and grabbed one to show how large they were, holding it up to herself for scale.

“It’s funny to think of him standing at Kroger like ‘I’ve got to have pads in the house! What if somebody needs them? What if they have literally nothing on hand, and they have to use this grandma pad?’” Frodge said later, laughing. “That’s the kind of thoughtful that Brent is.”

Frodge said this thoughtfulness extends to every aspect of Andrews’ caregiving as a friend, EMT and nurse.

“I’m pretty sure his love language is acts of service, and he wants to show that to others,” Frodge said. “I think he understands that words are nice, but doing solid, tangible things for people shows that he was standing at the store and thinking of us.”

Last summer, when Frodge and Andrews attended the Hangout Music Festival in Gulf Shores, Alabama, Frodge got really sick and Andrews came back to the hotel to take care of her.

“Brent was literally at my bedside on his knees being a caretaker,” Frodge said. “In that moment, I didn’t wish that anyone else was there, because just him being in the room was comforting.”

Andrews said he’s unsure what he’ll do once he graduates in December. Though they have similar skill levels as nurses, paramedics typically make less than half their salary — paramedics make an average salary of about $33,000 compared to $70,000 for nurses, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Andrews currently makes $10.50 an hour as both an EMT and a student nurse.

“I get paid enough, but if this was my full-time career, and I was trying to feed a family with this, I would not make enough,” Andrews said.

Andrews said he wants to work somewhere fast-paced but people-focused, like the ER or intensive care unit, where he’d be in charge of treating one or two patients at a time and his job would be different every day. He said he’d likely continue working part-time as a paramedic after obtaining his certification because he likes the challenge.

“EMS is certainly known as the red-headed stepson (in healthcare),” Andrews said. “It’s a little misunderstood and kind of wild, so the people are fun to be around.”

Andrews said even though he confronts death so often, he’s still afraid of it. He doesn’t believe in a God or an afterlife, but more than death, he fears dying without living an authentic life and working too much to be there for the people he loves.

“I want to be honest with people in my life because I want them to know how I feel about them,” Andrews said. “I just want to be genuine. I don’t want to waste my time not being who I want to be.”

Leaning back in his chair with his eyes lost in thought but the remnants of a smile still on his face, he said he thinks a lot about how he wants to die and what he wants his own last moments to be like.

“At the end of the day, we’re so small. I’m one person out of billions,” Andrews said. “I hope there are some people where I can just feel like I was there for them in a time of need.”