Walking around campus on Oct. 1, 2019, students were subject to an environment that had never happened before. At 98 degrees, it was the hottest October day in Bowling Green’s recorded history. The temperature came near the end of a late summer, early autumn heatwave that combined prolonged extreme heat with less than half an inch of precipitation between Aug. 28 to Oct. 5.

Although that time of year can trend hotter and drier, this event acts as one of the extreme occasions that could be seen more and more with climate change, said Stuart Foster, Kentucky’s state climatologist and a geography professor at WKU.

His large, square office sits at the end of the long third floor hallway of the Environmental Science and Technology Building. With his desk situated at the opposing corner of the doorway, Foster’s location, in a way, is the end of the road for climate discussion in Kentucky.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)Foster has been the state’s climatologist since 2000. He works with various state agencies and the general public to monitor Kentucky’s climate, including in his position as the co-chair of the state’s Climate and Water Resources Data Team — which is designated in the Kentucky State Drought Mitigation and Response Plan — where he helps contribute to statements regarding drought conditions as they develop, which are then released through the governor’s office.

Foster said climate change was certainly an issue when he started the position two decades ago.

“People were as concerned then as now,” he said. “It seems to be a growing public awareness that it’s real.”

Although the sun blazed down over Bowling Green during that aforementioned extended drought, Foster said Kentucky’s most notable effect from climate change has been the amount of rain the state has received each year. A smoothing curve, which helps average data by tracking trends, shows average precipitation in Kentucky has risen from just over 46 inches in 1895, the year national weather data begins, to over 54 inches in 2019, according to a chart from the Kentucky Climate Center.

“The way we’re impacted is more of the notion of an increased frequency in extreme events like flooding, flash flooding and drought,” he said.

Foster said the temperature in Kentucky has not risen considerably, as it is a part of a “warming hole,” a region that hasn’t experienced significant warming from climate change, from the Southeast to the Midwest. Although some explanations have been offered on why this warming hole exists, he said there is still active research to understand the causes.

He also said this warming hole leads to some push back on climate change’s validity, but temperature rise isn’t the only factor in climate change, a term often confused with global warming.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)Global warming is “the increase in Earth’s average surface temperature due to rising levels of greenhouse gases,” according to an article published by NASA. The same article said climate change is “a long-term change in the Earth’s climate, or of a region on Earth.”

Despite being in this warming hole, the region’s temperature has changed. Foster said it has been 40 years since the last “harsh” winter in Kentucky — which has no technical definition — but is notable in another chart from the Central Climate Division. The chart shows that, although average winter temperatures have gone up and down on a smoothing curve before, the average temperature has been rising since the ‘70s and is at a higher average now than ever before.

Temperatures have dipped well below average in that 40-year period in the region, but there has rarely been a prolonged period beyond a few days, Foster said.

“Forty years used to be 20 years,” he said of the previous length of time between those winters.

In the summer, daytime high temperatures have remained stagnant while low temperatures have risen. The increasing amount of precipitation has some impact on this phenomenon.

“We’re more humid, so highs are depressed and lows are elevated,” Foster said.

Since 1895, three of the top five wettest years in this region have come in the last decade, including in 2011, 2018 and 2019, according to a Kentucky Climate Center chart on annual precipitation. Foster did caution that one decade is a short period in climatology and that evidence is more apparent over a longer time, but the comparisons to previous decades helps to interpret this development.

“When you’re one person out of 7 billion, there’s not a whole lot to do,” he said regarding the action people can take to combat climate change. “But you get up in the morning and look at yourself in the mirror. You have the responsibility.”

One of the implications from climate change comes in the form of agriculture — Foster referenced the flooding in the Midwest in 2019 that prevented farmers from being able to plant. Some local farms have turned to more sustainable methods of growing, or “regenerative growing,” said Jackson Rolett, the owner of Scottville’s Stonehouse Market Farm.

Rolett’s farm grows more than 30 types of vegetables year-round, according to its website, using “bio-intensive, no-till methods.” Tilling is the process of breaking up the soil to prepare crops, but Rolett uses a no-till approach because the soil will remain fertile for much longer.

“No-till can be profitable in almost every context — better for the land, the farmers, and the communities they serve,” according to No-Till Growers’ website, a side project of Rolett’s.

Rolett said this type of farming should be developed now because as climate change develops and potentially gets worse, established and stable farms are needed. Part of his work includes convincing already-established farms to try new methods.

“People here say you can’t farm organically and maybe not conventionally,” he said. “All of this is new. You can read the instructions from (the University of Kentucky), but this practice is more of a response, which is much harder to copy and paste.”

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)Rolett has been farming for five years, and although he sees some advantage in being new — he is more adaptable to new techniques, for one — he also understands the hesitancy of established farmers to try these methods because they have generations of success in their business with what they already do.

Looking ahead, Rolett, who has a psychology degree, is interested in seeing how the individualism of farming turns more into a cooperation with several families combining their resources to make one farm business.

“Working with other families can make the crops produced more diverse for one farm,” he said. “It’s more emotionally sustainable, too, because people can take off time and not worry about the business. Somebody will always be around to take care of it.”

The financial side of farming can take a hit too. Max Farrar, the owner of Majestic Greens Farm in Oakland, said the historic drought last year increased the farm’s water bill. The crops that ordinarily sprung to life in their greens and yellows to provide sustenance to people instead rotted from a lack of their own sustenance.

“We had pounds and pounds of squash we weren’t able to market,” Farrar said. He also said farms in eastern Kentucky have had clear impacts because of winter 2019-2020’s volatile temperatures.

Farrar believes the issue of climate change can be tackled by political leaders who can enact national policies. So far, he has described their attempts as “lackluster,” and he’s made his opinions no secret to one of the highest powers in Washington, D.C.

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was speaking at a Republican Party fundraising event in Cave City on Feb. 8 when Farrar interrupted him from across the long room of fine dining and well-dressed attendants.

McConnell was about to address a question about what it is like to be the majority leader when Farrar loudly asked, “Is it like not leading on the climate crisis?” Attendants ducked their heads and kept eating their dinner until one man yelled out for Farrar to go home. Another man stood, pointed his index finger at Farrar, and told him “Go home!” as more people joined in on the chant. Farrar, shouting about his experience as a farmer, stood his ground against McConnell and his congregation of supporters.

As he was tugged out of the room by one attendant and a security guard, which can be seen on the YouTube channel of Sunrise Movement Bowling Green KY, Farrar shouted out, “You are a coward, and you are selling out our children’s future!”

After a thunderous applause for Farrar’s removal, McConnell thanked Farrar for the unpaid entertainment, drawing a laugh from throughout the gallery.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: “1”)Farrar is a member of the Sunrise Movement and said standing up to McConnell was cathartic.

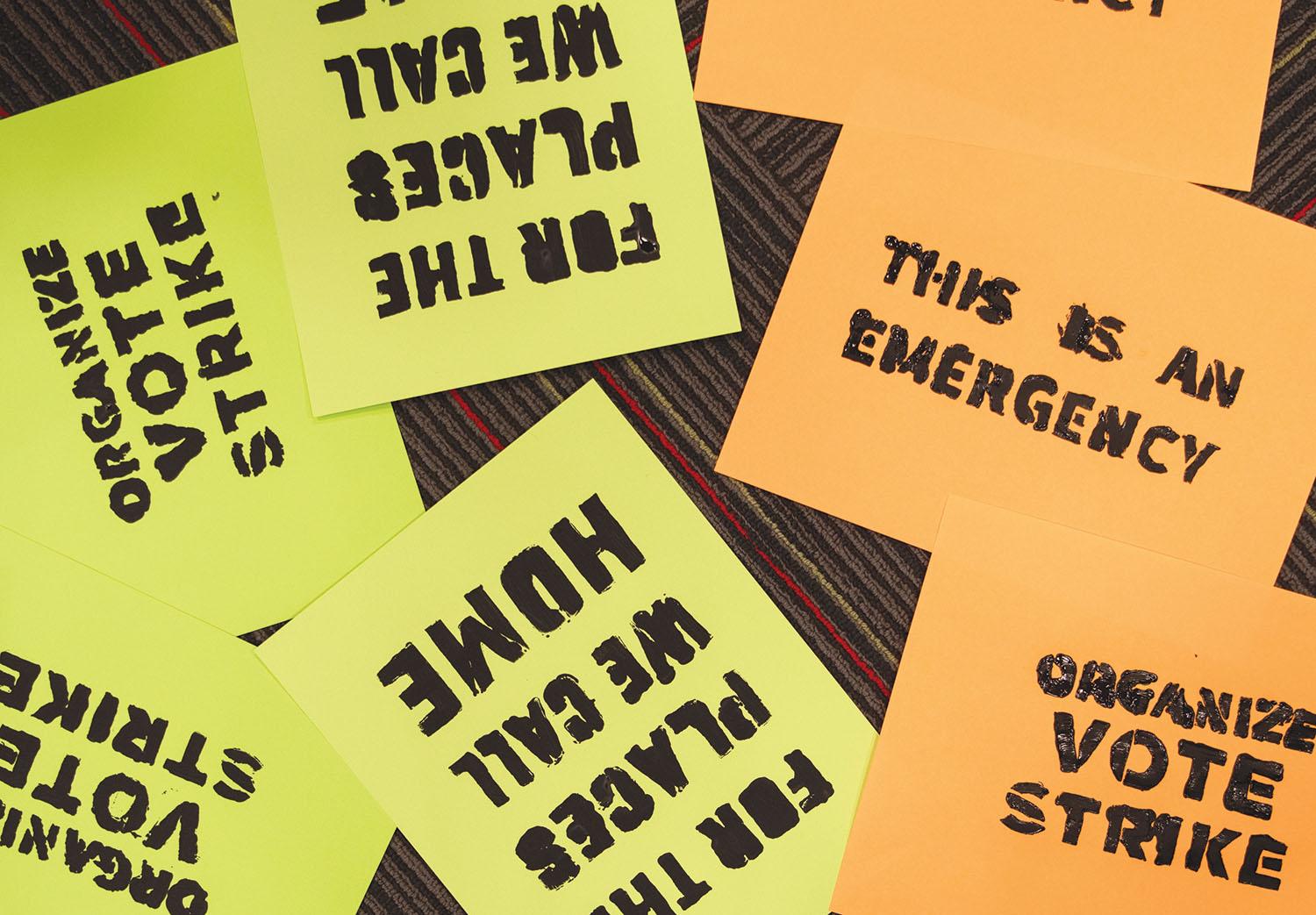

The Sunrise Movement is “a youth-led movement to stop climate change,” according to the Bowling Green branch’s Facebook page.

“We found out only a few hours before the event he would be in Kentucky,” Farrar said, explaining why he was alone in his heckling. “We want to be able to step aside and say that new change is coming.”

The Sunrise Movement doesn’t want to stay silent about climate change, said Fort Wright senior Claire Kaelin, Bowling Green’s hub leader.

“I think that our organization believes it is time to be disruptive,” Kaelin said. “It is not really a time to sit back and twiddle our thumbs and say, ‘Hey, um, climate change is happening and, if you could, maybe like, help us?’”

Kaelin’s role includes organizing events like climate strikes and the Earth Day strike. She said they have a bail fund for civil disobedience events like a planned sit-in at McConnell’s office for their Earth Day festival which was scheduled for their Earth Day festival on April 22, but the event ended up being remote because of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Although she doesn’t farm, Kaelin has learned about sustainable living through a three-week study abroad program in Costa Rica during the 2020 winter term. She said there were little things that demonstrated the society’s commitment to sustainability.

“On campus, there were signs that said ‘Take a five minute shower’ and then after five minutes the water got really cold, so you wanted to get out,” she said.

Being climate-friendly in Bowling Green has gotten more difficult with the end of Southern Recycling’s pick-up service on March 31. Its drop-off service was scheduled to end on July 31, but it closed to the public on April 6 due to concerns with COVID-19, according to its website. Southern Recycling’s services are ending because they are losing $30,000 each month, according to a Feb. 3 Herald article. The company would need to charge residents $18 a month, up from the current $2.65 a month, to cover their operations, and there are fewer buyers of recycled products, according to the article.

Kaelin said people could continue to bring their recycling to WKU, which she already recommends to people whose apartment complexes don’t recycle. WKU is not partnered with Southern Recycling, but WKU Recycling announced via Instagram on March 20 that it was temporarily discontinuing its community recycling bins.

Although Kaelin believes current climate change action is very late, she doesn’t think we are past a point of no return.

“I don’t think that it’s too late,” she said, “but it easily could be if we keep twiddling our thumbs.”